COIX: FOOD AND MEDICINE

by Subhuti Dharmananda, Ph.D., Institute for Traditional Medicine, Portland, Oregon

Coix is the common name for the Chinese medicinal material Coix lacryma-jobi seed. The entire coix plant and its seed pod are commonly called Job’s Tears, which is the English equivalent of the Latin species name (lacryma = tears): the seed pod often has a tear drop appearance. Linnaeus gave the botanical name in 1753, relying upon an existing popular reference for the tear shaped pods to the Book of Job (e.g., Job said: “before God my eyes drop tears”); it has also been called St. Mary’s tears. World-wide, this plant is best known for those pods (pericarps), which have a hole naturally occurring at each end, making them a useful source of beads for stringing. One popular application is making rosaries, as the beads are especially resistant to damage by moisture and have a valued symbolism of tears.

Coix is the common name for the Chinese medicinal material Coix lacryma-jobi seed. The entire coix plant and its seed pod are commonly called Job’s Tears, which is the English equivalent of the Latin species name (lacryma = tears): the seed pod often has a tear drop appearance. Linnaeus gave the botanical name in 1753, relying upon an existing popular reference for the tear shaped pods to the Book of Job (e.g., Job said: “before God my eyes drop tears”); it has also been called St. Mary’s tears. World-wide, this plant is best known for those pods (pericarps), which have a hole naturally occurring at each end, making them a useful source of beads for stringing. One popular application is making rosaries, as the beads are especially resistant to damage by moisture and have a valued symbolism of tears.

The seeds (caryopses) of Coix lacryma-jobi are used as a source of food, sometimes called adlay seed; a variety of the plant (var. ma-yuen = var. adlay) having relatively softer pods is relied upon for this use, while hard shell pods are used for beads. The plant is of the grass family that produces several edible grains such as wheat, corn, millet, and barley, and though more closely related to corn (maize), the coix seed has a size and appearance approximating that of barley, and has been referred to as coix barley. Most commonly, the food material is polished (the brown hull is removed) and therefore described as “pearl barley” (however, the term pearl barley is equally applied to ordinary barley that has been polished, so this is not a specific designation for coix). Coix barley has a rather strong taste among the food grains (though considered tasteless from the herbal perspective), similar to barley; coix is usually consumed in relatively small quantities (about 30 grams dried seed per serving) mixed with glutinous rice (“sticky rice”) or mixed with an equal proportion of brown sugar. Coix has a good protein yield compared to rice, up to double; more than half the coix seed is starch. This grain is native to Southeast Asia, ranging from India (its likely point of origin) through Malaysia to China; it is now cultivated elsewhere. Its use as a food in Asia, both for humans and animals, declined after the introduction of other grain crops with higher yields, such as corn and sorghum.

The seeds (caryopses) of Coix lacryma-jobi are used as a source of food, sometimes called adlay seed; a variety of the plant (var. ma-yuen = var. adlay) having relatively softer pods is relied upon for this use, while hard shell pods are used for beads. The plant is of the grass family that produces several edible grains such as wheat, corn, millet, and barley, and though more closely related to corn (maize), the coix seed has a size and appearance approximating that of barley, and has been referred to as coix barley. Most commonly, the food material is polished (the brown hull is removed) and therefore described as “pearl barley” (however, the term pearl barley is equally applied to ordinary barley that has been polished, so this is not a specific designation for coix). Coix barley has a rather strong taste among the food grains (though considered tasteless from the herbal perspective), similar to barley; coix is usually consumed in relatively small quantities (about 30 grams dried seed per serving) mixed with glutinous rice (“sticky rice”) or mixed with an equal proportion of brown sugar. Coix has a good protein yield compared to rice, up to double; more than half the coix seed is starch. This grain is native to Southeast Asia, ranging from India (its likely point of origin) through Malaysia to China; it is now cultivated elsewhere. Its use as a food in Asia, both for humans and animals, declined after the introduction of other grain crops with higher yields, such as corn and sorghum.

The seed used as a Chinese medicinal ingredient is called yiyiren 薏苡仁 (ren = seed; two characters pronounced yi, with different tones, together designate this specific plant); in common parlance, it is simply called yiren or yimi (the yi grain).

Coix was first mentioned in the Shennong Bencao Jing (ca 100 A.D.), mainly for use in treating people with stiffness attributed to inability to contract or stretch the sinews and for “bi syndrome” due to wind-damp (1). In the Jingui Yaolue (ca 200 A.D.), the combination of coix and aconite was one of the recommended treatments for a syndrome of “thoracic paralysis (2).” The use of coix for stiffness in the limbs (inability to stretch or bend) is preserved to this day in Japanese practice (Kampo) with Yiyiren Tang (Coix Combination), first introduced by Huang Fuzhong in his book Mingyi Zhizhang (1502 A.D.) and brought to Japan during the major transfer of the Chinese herb system that took place in the 16th and 17th centuries (3–5). In a recent publication about simple remedies (6), a treatment for lumbar pain and stiffness due to myofibrositis was described: 60 grams coix plus 30 grams white atractylodes (baizhu), decocted and taken as a one day dose. These are two of the important ingredients of Coix Combination (which also contains ma-huang, tang-kuei, cinnamon twig, peony, and licorice). Coix Combination is known among Kampo practitioners as a remedy for early stage and mild forms of arthritis (5). In fact, one of the first Chinese herb formulas marketed in America direct to consumers was Coix Combination, sold in the early 1980s. It later became known as “Mobility 1,” part of the “Chinese Traditionals” line of formulas. Mobility 1 was discontinued when ma-huang became a problematic ingredient, but Mobility 2, which is used for later stages and for more severe arthritis, is still available.

In recent decades, the original indications for use of coix became less frequently mentioned, and, instead, coix became better known as an herb for promoting diuresis in cases where moisture retention occurred secondary to impairment of the internal (yin) organs that circulate and eliminate moisture (spleen, lungs, kidney), with the main effect of the herb being on the spleen. It is considered to have an effect similar to that of hoelen (fuling). Though yiyiren is one of the weakest of the herbal diuretics (7), it is utilized with other herbs to control fluid problems, as in the traditional formula Shen Ling Baizhu San (Ginseng and Atractylodes Formula) where coix is combined with several spleen tonics and moisture-resolving herbs to treat chronic weak digestion with loose stool.

The fluid removing use of coix is represented in the book Chinese Medicated Diet (8), such as in this recipe for treating ascites secondary to liver cirrhosis:

Red kidney beans: 30 grams

Coix: 30 grams

Polished round-grained rice: 30 grams

Tangerine peel (chenpi): 3 grams

These ingredients are to be boiled to make a gruel that is taken in two meals during the day. The same book also has a recommendation for making gruel of coix with bush-cherry seed (yuliren) for treating benign prostatic hypertrophy, a disorder which often causes urinary retention. And, as a tonic for alleviating a wasting disease (with loss of appetite, cough, fever, and sweating, as occurs, for example, with tuberculosis), its recommendation is:

Dioscorea (shanyao): 60 grams

Coix: 60 grams

Persimmon frost (shibingshuang): 24 grams

Dioscorea and coix are first cooked until completely softened; then the persimmon frost (which is the white material appearing on the surface of dried persimmons, being 95% sugar and containing some other ingredients from the persimmon fruit, considered good for nourishing the lungs) is dissolved in the gruel. This food is consumed in two portions for one day. Dioscorea, coix, and hoelen are key ingredients of nutritive tonic food known as Sishen Tang, which is often cooked with pork or other meat to help those with gastro-intestinal weakness.

Coix is attributed a cooling property. Hence, Jiao Shude (9) notes that for treating stiff sinews, one would select the slightly warming herb chaenomeles (mugua) when the problem is associated with damp-cold, but would select coix when then problem is associated with damp-heat. In the book Chinese Medicinal Teas (10), a recipe for the wind-damp syndrome with slight heat and swelling (which calls for use of an herb that is cooling and diuretic) is 30 grams coix and 10 grams siler (fangfeng). The cooling property of coix is a mild one which is eliminated by frying, a process used to make the herb better suited for spleen-cold syndromes.

![]()

Coix gained a reputation for beautifying the skin, so women in Southeast Asia have been encouraged to eat coix as a cereal grain, making it a regular practice to improve complexion. A highly concentrated extract of coix produced in Japan (where it is known as hatomugi or yokui-nin) is promoted as a support for beautiful skin, hair, and nails. Coix has been included in medicinal formulas for treating skin diseases, such as acne and other swellings. A simple food recipe for treating acne is to combine 60 grams of coix with 30–60 grams of rice: cook and add sugar to taste. In Kampo, the formula Shiwei Baidu Tang (Bupleurum and Schizonepeta Combination) is frequently prescribed for skin eruptions; as relayed in the book Commonly Used Chinese Herb Formulas with Illustrations (3): “Better results are obtained in the treatment of suppuration and in nourishing the skin when coix is added to the basic formula.” The application of coix for treating localized infections is generalized to treatment of suppurating abscesses of the lungs and intestines. A formulation based on this general indication is produced at ITM, combining coix extract with blood vitalizing and anti-toxin herbs (11). Anti-allergy properties have been suggested for coix, so that this seed is sometimes used in treatment of allergic dermatitis (12). Coix is also used topically in creams and lotions, said to clarify the skin, prevent skin aging, and reduce blemishes.

Coix gained a reputation for beautifying the skin, so women in Southeast Asia have been encouraged to eat coix as a cereal grain, making it a regular practice to improve complexion. A highly concentrated extract of coix produced in Japan (where it is known as hatomugi or yokui-nin) is promoted as a support for beautiful skin, hair, and nails. Coix has been included in medicinal formulas for treating skin diseases, such as acne and other swellings. A simple food recipe for treating acne is to combine 60 grams of coix with 30–60 grams of rice: cook and add sugar to taste. In Kampo, the formula Shiwei Baidu Tang (Bupleurum and Schizonepeta Combination) is frequently prescribed for skin eruptions; as relayed in the book Commonly Used Chinese Herb Formulas with Illustrations (3): “Better results are obtained in the treatment of suppuration and in nourishing the skin when coix is added to the basic formula.” The application of coix for treating localized infections is generalized to treatment of suppurating abscesses of the lungs and intestines. A formulation based on this general indication is produced at ITM, combining coix extract with blood vitalizing and anti-toxin herbs (11). Anti-allergy properties have been suggested for coix, so that this seed is sometimes used in treatment of allergic dermatitis (12). Coix is also used topically in creams and lotions, said to clarify the skin, prevent skin aging, and reduce blemishes.

A good rendition of the use of coix at the end of the 19th Century was given by two medical doctors working in China (13):

It is said that the famous general Ma Yuen (A.D. 49) introduced the plant into China from Cochin China [today called Vietnam]. It does not flourish so well here as it does in the Philippines, where the Chinese settlers make a kind of meal of the seeds, which is very nourishing for the sick. The seeds [seed pods] are hard and beadlike, and [the seeds] are somewhat like pearl barley, for which they are sometimes mistaken in the Customs lists, and for which they make an excellent substitute. However, they are larger and courser than pearl barley. The unhulled corns are often strung by children as beads, and priests are sometimes seen using the largest ones in their rosaries. The seeds are considered by the Chinese to be nutritious, demulcent, cooling, pectoral, and [the root is] anthelmintic. Given either in the form of soup or congee [gruel], it is highly recommended by native doctors. It is considered to be especially useful in urinary affections, probably of the bladder. A wine is made by fermenting the grain, and is given in rheumatism….

General Ma Yuen is said to have thrived on eating coix seed, so he enthusiastically promoted its cultivation in China. A modern rendition is given in the text Maintaining Your Health (14):

Sweet, tasteless, and slightly cold-natured, coix can promote water metabolism, remove dampness, strengthen the spleen, relieve the stagnation syndrome of qi and blood, clear away heat, and discharge pus. It is administered in the treatment of urinary difficulty, edema, diarrhea due to spleen deficiency, rheumatic arthritis, pulmonary abscess, pulmonary tuberculosis, and cancer. Furthermore, coix may be used as a tonic for health care, suitable for people old and infirm, especially with stiff limbs. Often taking this herb will promote body vigor.

In this book, the diuretic aspect of coix is employed in a weight loss and lipid lowering tea made with oolong tea, coix, lotus leaves, alisma (zexie), crataegus (shanzha), and citrus (chenpi). Coix is also described as a food made with rice to form a gruel: “If the aged and the middle-aged eat it regularly, they may enjoy the effect of preventing diseases, building up the body, retarding aging, and prolonging life,” indicated specifically for “senile edema, spasm of the muscles and tendons, and numbness and pain due to wind-dampness.”

Active Constituents and Dosage

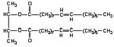

![]() A search for active constituents in coix, a seed which is mainly comprised of ordinary grain ingredients, such as starch and sugars, protein and amino acids, some trace amounts of vitamins and minerals, led to investigation of the oil fraction, which makes up about 5-7% of the dried seed. Two components isolated early on (in the 1950s) were coixol (see chemical structure right) and coixenolide; recently, coix extracts have been standardized to their coixenolide content (see chemical structure, left). Coixol is an agent that appears responsible for antispasmodic actions, perhaps explaining the traditional use in treating stiff conditions, while coixenolide, which makes up no more than 0.25% of the seed, has been investigated for antineoplastic activity (15). The spleen tonification and mild diuretic aspects of coix may be general properties of grains rather than specific to coix and its active components, as these are reported as indications for other grains used in Chinese diet therapy and medicinal formulas.

A search for active constituents in coix, a seed which is mainly comprised of ordinary grain ingredients, such as starch and sugars, protein and amino acids, some trace amounts of vitamins and minerals, led to investigation of the oil fraction, which makes up about 5-7% of the dried seed. Two components isolated early on (in the 1950s) were coixol (see chemical structure right) and coixenolide; recently, coix extracts have been standardized to their coixenolide content (see chemical structure, left). Coixol is an agent that appears responsible for antispasmodic actions, perhaps explaining the traditional use in treating stiff conditions, while coixenolide, which makes up no more than 0.25% of the seed, has been investigated for antineoplastic activity (15). The spleen tonification and mild diuretic aspects of coix may be general properties of grains rather than specific to coix and its active components, as these are reported as indications for other grains used in Chinese diet therapy and medicinal formulas.

Coixol has also been shown to have anti-inflammatory properties. It is one of the important constituents of another Chinese herb, phragmites (lugen). Phragmites is sometimes combined with coix, such as in a remedy for children who grind their teeth at night, and for cough due to pulmonary abscess, adding benincasa (dongguaren) and persica (taoren). Phragmites is also of the Gramineae Family that yields coix; the rhizome rather than seed is used, and it is said to have cooling nature; it is often used for disorders of the stomach and lungs.

The antineoplastic action of coix and coixenolide has drawn considerable attention. Several decades ago, the Japanese physician Yoshimi Okusa designed a formulation for treatment of stomach cancer that was marketed for some time in Japan, known as WTTC from the initials of the four ingredients: wisteria, trapa (water chestnut), terminalia, and coix. The inclusion of coix may have been from the suspicion that people who consumed coix as a food grain had lower incidence of stomach cancer, a cancer type that has been especially prevalent in Japan at the time (blamed, in part, on the high consumption of pickled vegetables). Use of WTTC in treating “digestive tract” cancers was reported in China as early as 1962 in the Jiangsu Journal of Traditional Chinese Medicine, with mention of work done in Japan during the 1950s, where one of the main proponents of WTTC was Nakayama Koumei of Chiba University. WTTC has mostly fallen into disuse as modern cancer therapies have developed; it was used as a potential aid for enhancing survival among stomach cancer patients following surgery, and it has been modified and used in treating some skin ailments. In a book about treating cancer with Chinese herbs (16), it was suggested that clinical data supported use of WTTC to help prevent recurrence of cancer, but the author gave this cautionary note based on a 1978 report from Japan: “WTTC is not a cure-all drug. Surgery, radiotherapy, and other anti-cancer preparations are usually employed in conjunction with it.”

As indicated in the book Anti-Cancer Medicinal Herbs (17), a recommendation made in China for cancer patients (such as those with cancer of the stomach or larynx) was to take 30-60 grams coix, made with glutinous rice as a gruel, every day, year round; the patients also received other treatments. Another recommendation was to combine 500 grams coix with 150 grams tien-chi ginseng (sanqi) and grind it to powder and take 15 grams each time, three times daily (a daily dose of about 34 grams coix and 11 grams tien-chi); this combination was given for the treatment of uterine fibroids (tien-chi is used to inhibit bleeding, a common fibroids symptom, as well as to vitalize blood circulation).

An extract of the oil of coix has been developed as an injection for potential treatment of cancer under the name Kanglaite, but the research is only in an early stage. Clinical studies were conducted in China during the 1990s, when it was used in liver and lung cancer cases; primarily, it has been used along with standard anticancer protocols in an attempt to improve outcomes (18).

Other substances, such as polysaccharides, called coixans, have also been isolated from the coix seeds and are being investigated for potential medicinal use, such as possible hypoglycemic effects (19). These and the other active components usually have to be isolated by technical means to get a large enough dose for easy administration in getting medicinal effects. For example, coixenolide is now being obtained by ultrasound-assisted supercritical fluid extraction.

The dosage of coix as an herb is explained well by Jiao Shude (9): “The dosage is generally 10-20 grams. However, this medicinal is bland in flavor and moderate in strength, so if the disease is severe, it is often necessary to use a larger dose, such as 30–60 grams, and to take it over a long period of time.” Along these lines, a suggested food therapy for people with cancer (8) is 30 grams each of coix, water chestnut, and Scutellaria barbata (banzhilian), decocted and taken in two portions per day, “for a long period of time.” In a trial of coix for dysmenorrhea, 100 grams of coix, taken as a thin soup, was consumed in one day with four portions (so, about 25 grams coix per portion) for three days before menstruation until the cessation of painful menstruation, said to have good therapeutic effect (20). Coix is also applied topically for improving skin conditions and treating skin disorders, such as warts, for which a recommended therapy is to consume 60 grams per day of coix, cooked in water, and to also apply powder of coix to the affected areas one or twice daily (treatment time is one to two weeks).

Potentially, daily consumption of about 30 grams or more of coix seed (e.g., made as a food or tea) over an extended period of time could provide certain benefits that have been implied by laboratory animal studies or described in the traditional literature. Special extracts, consumed in quantities of about 1 gram or more per day, might be used to get an adequate dose of specific active components, especially coixol and coixenolide.

References

- Yang Shouzhong (translator), The Divine Farmer’s Materia Medica, 1988 Blue Poppy Press, Boulder, CO

- Hsu HY and Wang SY (translators), Chin Kuei Yao Lueh, 1983 Oriental Healing Arts Institute, Irvine, CA

- Hsu HY and Hsu CS, Commonly Used Chinese Herb Formulas with Illustrations, 1980 Oriental Healing Arts Institute, Long Beach, CA.

- Dharmananda S, Kampo: The practice of Chinese herbal medicine in Japan, 2001 Institute for Traditional Medicine, Portland, OR

- Toyohiko Kikutani, Coix Combination, Bulletin of the Oriental Healing Arts Institute 1981; 6(1): 38–41.

- Xu Xiangcai (chief editor), Simple and Proved Recipes, volume 4 of The English-Chinese Encyclopedia of Practical Traditional Medicine, 1989 Higher Education Press, Beijing

- Yang Yifan, Chinese Herbal Medicines: Comparisons and Characteristics, 2002 Churchill-Livingstone, London

- Zhang Wengao, et.al., Chinese Medicated Diet, 1988 Publishing House of Shanghai College of Traditional Chinese Medicine, Shanghai

- Jiao Shude, Ten Lectures on the Use of Medicinals, 2003 Paradigm Publications, Brookline, MA

- Zong XF and Liscum G, Chinese Medicinal Teas, 1996 Blue Poppy Press, Boulder, CO

- Dharmananda S, A Bag of Pearls, 2004 Institute for Traditional Medicine, Portland, OR

- Hsu HY, et.al., Suppression of allergic reactions by dehulled adlay in association with the balance of TH1/TH2 cell responses, Journal of Agriculture and Food Chemistry 2003; 51(13): 3763–3769

- Smith FP and Stuart GA, Chinese Medicinal Herbs, 1973 Georgetown Press, San Francisco, CA

- Xu Xiangcai (chief editor), Maintaining Your Health, volume 9 of The English-Chinese Encyclopedia of Practical Traditional Medicine, 1989 Higher Education Press, Beijing

- Chang HM and But PPH, Pharmacology and Applications of Chinese Materia Medica, volume 2, 1987 World Scientific, Singapore

- Hsu HY, Treating Cancer with Chinese Herbs, 1990 Oriental Healing Arts Institute, Irvine, CA

- Chang Minyi, Anticancer Medicinal Herbs, 1986 Hunan Science and Technology Publishing House, Changsha

- Qian MS and Liu ZJ, Clinical Study on Kanglaite Injection Combined with Intervention Chemotherapy in the treatment of Primary Hepatic Carcinoma and Primary Pulmonary Carcinoma (2005): http://www.kanglaite.com/cn/A7.htm

- Takahashi M, et.al., Isolation and hypoglycemic activity of coixans A, B, and C, glycans of coix seed, Planta Medica 1986; 52(1): 64–65

- Zhang Yongluo and Hou Guangming, The analgesic action of Semen Coicis on severe functional dysmenorrhea, Journal of Traditional Chinese Medicine 2000; 20(4): 293–296.

August 2007