Painting by Virgil Nez |  Cheyenne Medicine Man by Howard Terpning |

ART AND TRADITIONAL HEALING

Native American Art and the Yei'bi'ci Winter Healing Ceremony

Traditional medicine relies heavily on symbolism, especially with reference to gods associated with healing and displaying images of patterns that have spiritual significance. The symbols are used in many ways, including as items of meditation, objects or decorations of objects used in healing ceremonies, or in representations of things that represent normality and health, the goal of the healing action.

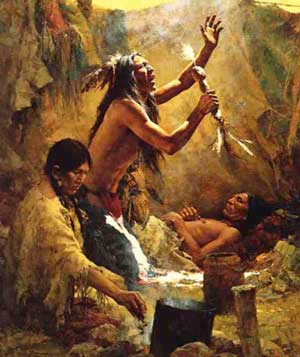

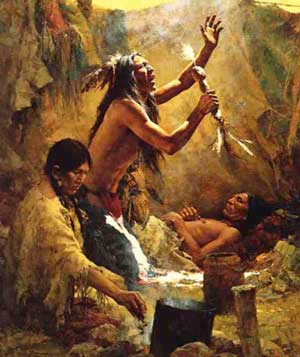

Although the artworks sometimes portray an actual medical encounter, as in this famous Howard Terpning painting Cheyenne Medicine Man (pictured below), more often traditional art presents the most fundamental symbols of the culture that can convey the mindset of the healer and the concept of the ultimate source of healing.

The art of Navajo artist Virgil Nez is a good example of someone capturing and conveying the cultural symbols which, among other things, communicate the integrity of the Navajo as a community of people. Virgil Nez currently resides on the Diné Bekayah (the Navajo Reservation), which is located between the four sacred mountains within the boundaries of Arizona, New Mexico, Colorado, and the State of Utah (called "Four Corners"). His home is at Many Farms, near Chinle, Arizona, fourteen miles down the mouth of the great Canyon DeChelly. He received his B.A. in fine arts in 1991 from North Arizona University and began receiving awards for his painting in 1992; he continues to win awards for his unique art style. In the February 2005 Arizona Sentinel (Let's Go feature), this report was filed with the picture below as illustration of his work:

Painting by Virgil Nez |  Cheyenne Medicine Man by Howard Terpning |

The 9th annual Scottsdale Indian Artists of America Show has selected Virgil J. Nez as its 2005 Featured Artist, an honor designated by the Arizona Indian Arts Alliance (AIAA) in conjunction with Southwest Art Magazine...."Virgil Nez represents both a dedication to his heritage and to his art form," said Don Owen, President of the non-profit AIAA…."If one is in tune with oneself, then one can feel and see the tradition dancing in the hot shimmering summer. In the winter, while visiting the Navajo Reservation, one can see the spirits dancing with the swirling snowflakes," said Nez. "At dawn, one can sense the laughing spirits in a hush of solitude that nature gives out. As an artist, I need this peaceful environment so I can dance with these creative spirits on my canvas. This is my art, and it is also my life."

Prayer is an important part of healing as well as daily life. Virgil Nez's painting below is an image of "grandma praying and giving an offering to the Yei'bi'chi (prayer warriors)." Nez points out that "We, the Dine' (the People), pray toward the eastern dawn and sprinkle our corn pollen to give offerings and thanks." The Yei'bi'chi participate in a major winter curing ceremony [see appendix] that lasts nine days. On the eighth day of the ceremony children are initiated by showing them the secret of these masked gods. They learn that the unique robe, mask, and headdress is symbolic of their gods and that their performance (involving dance and song) is important to their heritage. Adults also take part in this ritual: it is considered necessary for each Navajo to participate in the initiation ceremony four times during his lifetime. Virgil Nez participated in these in his youth and has captured the Yei'bi'chi in action on many canvases.

There are rock formations in Arizona such as that shown below that remind the people of the Yei'bi'chi form, and are worshipped as sacred places. Carvings depicting the Yei'bi'chi are also made by native artists, usually along with carvings of the more commonly known Kachinas.

Virgil Nez's painting of a grandma praying and giving an offering to the Yei'bi'chi (prayer warriors). |  Rock formations in Arizona. |

According to Deanne Durrett, in his book American Indian Lives: Healers:

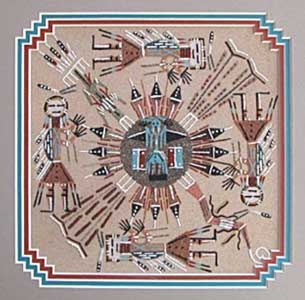

Navajo medicine men perform chants (a combination of prayers, myths, and poetry rendered in song) to cure patients by bringing them back in balance and harmony with the forces of the universe. Each Navajo medicine man, or singer, knows at least 35 chants. One chant may contain as many as 500 songs. Along with the words to these songs, each medicine man also knows several designs for sand paintings to be used with the chant. Each chant is designed for a specific illness….Before the ceremony begins, the medicine man and his helpers work for hours to create a sand painting….The patient sits or lays on the sand painting during the curing ceremony. Power is thought to be absorbed from the sacred objects depicted in the sand painting. During the chant, the patient relives events in the life of an ancient hero who was cured by the Holy People. Each sand painting must be destroyed before sunset and another painted the next day if needed. Many of the curing chants originate in the Blessingway ceremony, the backbone of the Navajo religion. This ceremony is used frequently (like preventive medicine) to keep harmony and balance in the lives of those who are sung over."

Virgil Nez also makes frequent reference to the Native American Church (NAC) in his paintings. This church (which has about 250,000 members) is partly based on ancient rituals and was formed about 1890, as the tribes were finally all confined to reservations. The Church makes use of a peyote ceremony, and has some Christian overtones that vary in extent of their contribution to the spirituality among the different tribes. Their prayer meetings are held in teepees (tipis). In the Virgil Nez painting shown below, the winter dawn ceremony is going on inside the teepee, and one can see the outlines of the people sitting around the fire. The two Yei'bi'chi are the Talking God and his brother, the Water Sprinkler. Although they are pictured outside the teepee, these represent the images that the people inside are seeing in their minds. Most NAC singers are also Yei'bi'chi singers; the two different ceremonies are often viewed as one. Nez believes that interweaving these two is a good thing.

The significance of the teepee to the Native Americans goes beyond its service as a shelter. Nez comments: "A teepee represents our mothers. The teepee poles are the rib cage. The earflaps are the out reaching arms. She is welcoming the holy light from the eastern dawn."

In this section, paintings and reports about the Yei'bi'chi ceremony are presented. The first and longest description is taken from a message posted on the Navajo Central website (www.navajocentral.org):

After the first frost of the Fall has passed, these nine-day long ceremonies may begin. They generally start late in the evening and last through the small hours of the morning. There may be some dancing in the afternoon, depending on the group. They are healing ceremonies invoking the aid of the Holy Ones and the Talking God. The most common is the Beautyway. These events are funded by extended families. Guests show good manners if they contribute to the host, or bring food to share. Generally, all who come are fed. This is a cost in excess of a hefty fee to the singer. Sometimes Yei dancers, in masks, powdered bodies and dress, will come into a community and solicit donations. There is generally no vocalism beyond the "wu tu tu tu" of the character….Some notes jotted down after attending a ceremony may give you an idea of the atmosphere surrounding a Yei'bi'chi:

In the parking area, several men struggled to slide a large package from the bed of a pickup. They carefully carried it across the parking lot and placed it on the earth about ten feet in front of the ceremonial hogan's door. Carefully unknotting the ropes that bound it, the covering was folded back exposing a brown mass that when unfolded, metamorphosed into a buffalo hide at least eight feet long, and nearly as wide. The hide was spread fur-side up on the packed earth.

The patient, an elderly woman, perhaps in her eighties was helped from the hogan to stand, facing the dance area, on the center of the hide. A red patterned wool blanket covered her shoulders and a traditional flat basket filled with corn pollen was slung on a crooked left arm. Openings in the sling allowed her to remove this sacred substance in order to dispense it as appropriate. At the other end of the runway, three shadowy figures appeared before the brush house. As they began dancing toward the hogan, a hush fell over the gathered crowd. After the blessing was over, the patient returned to the hogan and the dancers to the brush house. Through the layers of pine branches piled against the sides of the frame, one could see the orange flames of a dancing fire. The buffalo skin was carefully re-wrapped and carried off.

Soon, chants from male voices in a rhythm unique to the Dineh, could be heard through the hogan's walls….Like physicians leaving an operating room, a variety of men stepped through the hogan's door, pushing aside the blanket hung in front of it. They then vanished into the night. Some carried salesman's sample cases packed with jars and tins filled with different shades of sand. The contents had been used to construct a large sand painting depicting healing tools of the Holy Ones on the Hogan's floor. Having served its purpose, the remains of the painting itself, departed in a white, five-gallon plastic paint bucket, carried by another man towards the direction of the brush house.

In time, a large overstuffed chair was carried to the packed earth in front of the hogan by two younger men. Positioned facing the brush house to the East, a large comforter, perhaps an opened sleeping bag, covered the chair's seat. When the patient returned, she was seated and the corners of the comforter were used to cover her shoulders, head and legs. It would be her place of warmth for the remainder of the night. In time, a line of shadowy figures materialized before the brush house and in single file, began their trip to the patient. Protected only by kilts, boots, masks and ash or flour whitened skin, the dancers seemed oblivious to the 6,000 foot elevation's winter temperatures.

All in all, over thirty-five groups would travel from the brush house to the patient to bestow on her the blessings of the Holy Ones. Hours passed. Log by log, the wood piles shrank…. Finally, morning prayers began to be offered and soon the turning earth brought light again to the Eastern sky.

Additional insights into the Yei'bi'chi ceremony are obtained from the artists in Many Farms. In the painting below by Virgil Nez, he depicts two Yei'bi'chi dancers coming home at dawn after an all night ceremony. Nez writes: "It's about being pals; it's about brotherhood." While the Yei are the Gods, the Yei'bi'chi are their human impersonators who perform in the ceremonies.

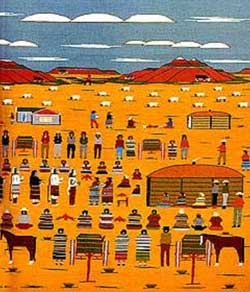

One of Virgil Nez's former neighbors at Many Farms, Navajo elder Isabel John, wove a large pictorial style rug in 1984 depicting the ninth and final day of the Yei'bi'chi' healing ceremony. This information and image come from Paula Giese (1997). Pictured below is the right half of it. Some of the dancers are seen in the middle, heading toward the healing place, the hogan at the right foreground. Another hogan and a small modern house are visible in the background. There are many spectators and sheep, and in the foreground are wagons and horses of those who have come for the ceremony. The mountains of Canyon de Chelly (visible from Isabel's house) line the background. The prominence of the hogan in Isabel's rug design reflects the fact that in the Yei'bi'chi and other ceremonies, all require hogans to be properly performed. Since it has been possible to get the wood for the larger, more comfortable hexagonal (or octagonal) hogans, almost no one has built the small, old, earth-covered fork-stick hogans, the kind whose building is explicitly described in the Blessingway. Hogans are used nowadays almost entirely for ceremonial purposes. A hogan is represented in the painting below by Virgil Nez.

The National Heritage Museum presented a display of Yei'bi'chi weavings (woven between 1910 and 1950) in an exhibit from April-September 2000. Following is an edited part of their report on this exhibit (full version: http://www.monh.org/pastexhibits/yeibichai/content.htm).

"The Yeibichai weavings are interesting and unique in many ways," said Rebecca Valette who, together with husband Jean-Paul, collected the rugs on view. "In spite of their sacred theme, these weavings never had any ceremonial use, as they were produced exclusively for sale to Anglo tourists and collectors." Yet because traditional Navajo beliefs expressly prohibit the reproduction of sacred figures in a permanent medium, the initial appearance of these weavings was criticized and often condemned by the tribal elders. "Their production today remains controversial among traditional Navajos."

The vast majority of Navajo weavings are non-figurative and have geometric and often symmetrical designs inspired by traditional and non-Navajo motifs. "By the beginning of the twentieth century, however," explained Jean-Paul Valette, "some weavers, with much hesitancy and great circumspection, began to introduce sacred motifs into their textiles at the prodding of traders. The traders quickly recognized the high market potential of rugs with sacred motifs…In order to reduce the potential ill effects of transgressing tribal prohibitions, Navajo women were extremely careful not to weave exact reproductions of the sacred images."

Traditional Navajos lead a deeply spiritual life striving to maintain the self in balance with the other elements of a complex universe. Their belief system includes a number of powerful supernatural beings known as Holy People. Generally indifferent to the actions of human beings, these divinities can dispense goodness, but can also be easily offended by improper human behavior which disrupts the harmony of the universe. To restore balance and promote tranquility, the Navajos have an elaborate system of curative ceremonies including the spectacular nine-day, nine-night Nightway, culminating in the Yei'bi'chi dance.

The Nightway invokes a special category of Holy People known as Yeis - beings generally well disposed toward the Navajos, together with their leader and grandmaternal ancestor known as Yei'bi'chi. The uniqueness of the Nightway stems from the physical appearance during the ceremony of the Yeis themselves, impersonated by masked and ceremonially attired Navajos. "On the final night of the ceremony, the Yeis execute a public performance," explained Rebecca Valette. "Hundreds of Navajos will come from all parts of the reservation to benefit from the benevolent presence of the divinities."