TRADITIONAL MEDICINE OF BHUTAN

Bhutan is a small country of 750,000 people in the Himalayan range between India (Assam and West Bengal) and Tibet, to the east of Sikkim and Nepal. It has been largely isolated from the rest of the world, until recently; today, only about 5,000 tourists per year venture to this kingdom. Bhutan shares many cultural aspects with Tibet, including the Buddhist religion as the dominant influence (the Kagyu sect of Tibetan Buddhism, with emphasis on Tantric Buddhism), and Tibetan traditional medicine as the basis for much of its health care until the introduction of modern medicine in the 1970s.

In Thimphu, the capital, there is Bhutan's Institute of Traditional Medicine Services sprawled on a hilltop, with the Traditional Arts Center and National Library just below. The Institute provides medical services, trains traditional doctors, and conducts research on Bhutan's medicinal plants to identify the ingredients in centuries-old remedies and help develop new health products. The Institute has a library of recipes dating back to the introduction of Tibetan Buddhism around 1616, collected from monasteries, which is where most of the medical lore has been retained by educated monks. Bhutan's medical institute is similar to the Mentsekhang (Tibetan Medical Institute), which is based in Lhasa and has a refugee branch in Dharamsala (India). Pema Dorji, the director of Bhutan's Institute, was originally trained at the Mentsekhang in Lhasa, prior to the Chinese take over.

As with Tibetan medicine, the main methods of diagnosis are feeling the pulse, checking urine, and examining the eyes and tongue, as well as interviewing the patient. Therapeutically, the Bhutanese rely on herbal combinations, limited acupuncture therapy (including use of the golden needle), applications of heat (usually with metal rods), and minor surgical interventions, all done in the context of Buddhist ritual. There is a hospital for modern medicine relied upon mainly for treatment of acute and severe diseases. Bhutanese herbal medicine is also similar to that of Tibet. Originally, herbal powders were swallowed down with warm water, but with the introduction of modern equipment, the herb mixtures are now produced as pills. The specific formulas used in Bhutan differ somewhat from their Tibetan counterparts in that there are local influences on the selection of herbs, but most of the key herbs are the same, as the altitude and climate conditions are similar to that of Tibet. A substantial amount of herbal materials-perhaps 30% of the total used-are imported from India and Nepal.

A European Union (EU) project to support traditional medicine in Bhutan was initiated in the year 2000. According to data collected as part of this project, there are about 600 medicinal plants used in Bhutanese traditional medicines, out of Bhutan's 5,600 identified species (a comprehensive Flora of Bhutan has been written recently, as part of another project that was started in 1975). About 300 of these herbs are used routinely and are at risk for ecological loss due to clearance of trees and over-collection of herbs. The EU has invested in having these herbs raised as cash crops to create jobs, provide a new medicine factory with raw materials, and protect the environment. The Bhutanese are producing 35 tons of herbal materials each year, partly as a result of these efforts.

It has been suggested that as many as 3,000 species of plant are used in Bhutanese medicines, but this figure no doubt includes substitutions (several species of the same genus, or plants having similar appearances, substituted for one another); local folk remedies; and double-counting of the species, as commonly occurs in plant surveys based on medicine samples. Neither Tibetan nor Bhutanese medicines have been subjected to strict studies, in part due to: their complexity (some remedies contain dozens of ingredients); variability (the content of the finished formulas vary both in terms of ingredients used and the natural variability of constituent levels within plants); and the unique traditional medical applications that are not well suited to modern testing. A few of the medicinal materials are toxic, limiting interest in further investigation.

A view of the traditional medicine situation in Bhutan can be gained by examining several news reports on the subject, presented below. All materials are quoted from the sources mentioned, with slight editing.

Silver earrings dangling in wisps of her pixie-cut gray hair, Tshering Chenzon leans forward on a stool with her blouse pulled up from behind while a doctor's aide aims a fine mist from a small garden hose at her lower back. The hose is connected to a pot of water, boiling with 27 traditional medicines on an electric burner, and Chenzon, 56, is on fourth visit to Bhutan's Institute of Traditional Medicine Services for treatment of her pain.

Another patient is having acupressure. A doctor presses-but does not prick-her skin with the tip of a heated golden needle. Traditional doctors in this Buddhist kingdom in the Himalayas say conductivity varies with different metals, shapes, temperatures and the part of the body touched.

The instruments for nasal irrigation, bloodletting, massage, and stone-heated baths are nearby. The institute's walls have charts of pulse and humour points. Traditional doctors make their main diagnosis by feeling the pulse, checking urine, the eyes and tongue and from interviewing the patient.

A Buddhist monk may get more benefit from the treatment than a Westerner of another religion, says the institute's director, Pema Dorji. "Medicine is medicine," Dorji says. "It should be the same for all. But when we talk about medical treatment, psychology also plays a role." He says the major difference between traditional and Western medicine is that "in our system we target organs, while in modern medicine, the targets are microorganisms."

Traditional medicine has been an official part of Bhutan's public health system along with Western-style medicine for more than three decades. The institute treats chronic diseases such as arthritis, rheumatism, liver and nervous disorders. Patients with acute diseases, such as cancer, are referred to a Western-style hospital.

Nomadic yak herders are employed to gather new plants when researchers go out to interview village healers. "The village healers are not wrong," says Dorji, who studied in Tibet before it was closed off by the Chinese takeover in the 1950s. "What they are doing is beneficial to the people sometimes. But their methods are crude."

For bloodletting, healers would use unsanitary blades, for example. The institute uses outreach clinics to encourage healers to change some practices and improve others. For instance, leeches are used for bloodletting in some parts of Bhutan. They are plentiful in the lower valleys in the monsoon season and Dorji says they are better than a dirty blade and less traumatic for a patient whose blood pressure rises as he contemplates being cut. "There are two kinds of leeches. One sucks. The other is poison. A person has to be well-qualified to identify them," he says.

Bhutanese fought off Tibetan and British attempts to take over their territory and remained isolated from foreign visitors until 1974, allowing protection of many rare plants and animals. Medicines made from grinding those ingredients into powders, teas, pills, lotions and syrups are sold at the institute and are stored in airtight containers in pristine rooms. With aid from the European Union, the institute began in the 1980s to produce pills, which allows for a more exact dosage than powders wrapped in papers. Also, most herbal medicines taken with hot water on an empty stomach are bitter, so a pill is easier to swallow.

"The reason for using this modern technology for manufacturing is we are keeping in mind we may export," says research assistant Sonam Dorjee. "For example, it may go to America, where we would have to comply with FDA rules."

Traditional medicine became part of the public health system in 1967 and the government plans to have a traditional medicine center and a Western hospital in all 18 districts of the 46,500-square-mile country by next year. "Government policy is to give a choice to patients and to do cross-research to find which system is best for a disease," Dorjee says. Dorjee dreamed of being a doctor, but his family of 10 could not afford medical school. Now he spends most of his time on computers, mapping the chemical contents of the minerals, plants and animal parts that make up the medicines that Himalayan monks and village healers have used for centuries.

At a time when anything that is traditional is indiscriminately put aside vis-à-vis modern science, Bhutan has a unique opportunity to rise above the challenge posed by modern development. It can keep pace with discoveries of the last century without losing valuables indigenous knowledge. One important field is traditional medicine.

Traditional medicine was first introduced into Bhutan around the 17th century after the arrival of Zhabdrung in 1616. Tibetans had always referred to Bhutan as Lhomenjong, or the valley of medicinal herbs because of its fertility, mountains, and varieties of medicinal plants that are found at different altitudes ranging from 200 to 7800 meters above sea level.

After the sixteen century, Bhutanese went to Tibet to learn medicine. The principal of reciprocity- whereby Tibet provided schools for training Bhutanese doctors, and Bhutanese doctors in turn transported medicinal plants as far as Lhasa or Kham-was practiced. Most of the trained doctors would return to Bhutan and set up their own practices in monasteries or dzongs (fortress monasteries). Traditional medicine was greatly supported especially after 1885 when the Poenlops and Dzongpoens (regional leaders) patronized the profession. The courts privately employed or kept at least one or two physicians.

The Traditional medicine service was officially started as an offshoot of the Department of Health services. While the Government bore the main brunt of finance, the international agencies, like WHO and UNICEF, were involved. In 1967, the Government recognized the scientific and cultural importance of traditional medicine. After it became a part of national health system people were given the choice of opting for allopathic and traditional medicines. In 1979, two traditional dispensaries and a school for traditional medicine were established in Thimphu. The donation of some pharmaceutical machines in 1982 by WHO enabled it to start planning expansion of dispensaries to other districts such as Punakha, Trashigang, Trongsa, Bumthang, and later Haa. Opening of other traditional dispensaries in all districts began slowly.

In 1988 the Government established a Coordination Centre at an indigenous dispensary in Thimphu. These facilities included a laboratory, outpatient department, hostel and a library for training. It made possible the introduction of modern scientific methods into practices of traditional medicine. Plants and other materials used in medicinal formula were tested for their chemical and pharmaceutical contents. Over the next four years, the National Institute of Traditional Medicine (NITM) was established. NITM, as the centre for development of traditional medicine, became a base for future development of traditional medicine, with activities including, training (of traditional compounders and physician-pharmacists), research, production of medicine, and treatment of patients. The institute now has a pharmaceutical production capability (called Menjong Sorig Pharmaceuticals) and is assessing the possibilities of marketing its herbal products to the West [see the article on a medicinal tea product, below].

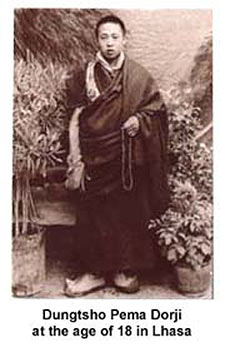

It was Dungtsho (physician-pharmacist) Pema Dorji who institutionalized traditional medicine in Bhutan. His grandfather, Dungtsho Chimi Gyeltshen treated Ashi Om, the Queen of His Majesty Jigmi Wangchuck. She instructed him to pass on the practice to his grandson and in 1946 Pema Dorji left to train as a Dungtsho in Lhasa Chakpori in Tibet. He qualified in 1953 and returned to Bhutan where he worked for 9 years under his uncle, Neten Tsewang Gyeltshen in Trongsa Dzong. In 1968, with Dungtsho Sherab Jorden, he laid the foundation stone for the first traditional hospital to be set up by the government in Dechencholing. The principal indigenous hospital functions were transferred to the new indigenous hospital in Kawajangsa, which was opened in 1979.

Dip one sachet of tea into a cup of hot water (no sugar or milk required), and brew for a few minutes to get the best flavor and color. The tea not only gives a soothing and refreshing sensation but is supposed to improve the conditions of your heart, liver, nerves and the digestive system. And there are no known side-effects. Great benefit for a small price. But like any other Bhutanese traditional medicine, to reap the benefits, the consumption should continue for a long time.

The sachet contains the Tsheringma herbal tea, just introduced into the market by Menjong Sorig Pharmaceuticals, a unit of the Institute of Traditional Medicine Services. The tea is the first commercial product of the institute, along with a medicinal incense under the same brand name. It is named Tsheringma after the goddess of longevity, wealth and prosperity.

The tea consists of only two ingredients. The main ingredient is Carthamus tinctorius flowers (gurgum in Bhutanese; it is the common safflower) which is a cardiac and nerves tonic. It has a cooling effect, which according to traditional medical literature is good for curing all types of liver diseases. The safflower is not grown naturally in Bhutan but can be cultivated, and is readily available from India. The other ingredient is the root bark from Cinnamomum tamala (Bhutanese name: shing-tsha), which adds flavor, aids digestion, and stabilizes bowel movements. The plant (known as Indian Bay Leaves, displayed here) is naturally grown in Bhutan and is found in the sub-tropical forest; the plant is also found in northern India.

Cinnamomum tamala, also known Indian bay leaves |  Enjoying tea in Bhutan. |

According to Ugyen Dorji, marketing officer of the institute, research on the formulation had started early last year. He said that though a comprehensive scientific research was not done, there were no known side effects. According to the traditional medical literature, traditional medicines never had any known side effects. The objective of the institute is to "become slowly sustainable and also to explore the possibilities of producing natural products for the world market as a contribution to the country's economy by using the biodiversity in a very sustainable way....Right now, we have no plans to sell outside the country."

The Tsheringma herbal tea is available for Nu 50 a box (about $1.20 U.S.) containing 25 neatly-packed sachets. The pharmaceutical unit started using the modern imported machines to produce the traditional medicines in December 1998. The machines, with a capacity to produce two tons of herbal tea in a year, made production systematic, increased output, and improved quality and hygiene. Speaking at the launching ceremony on Monday, Dr. Gado Tshering, director of health, urged consumers to leave tea, coffee and alcohol for Tsheringma herbal tea. But, he added, more studies had to be carried out after surveying the consumers. The institute, meanwhile, wants to apply for patent and trademark rights for the product. Under the motto "promoting health and happiness the natural way," the institute will soon be coming out with another product-an herbal drink (which is not carbonated and has no artificial colors or preservatives) from the medicinal plants. These herbal products may just be the beginning of many more to come.

Bhutan, the kingdom of the peaceful Dragon, used to be called Men Jong, Land of Medicinal Plants, because of the fertility of its valleys and the luxury of its forest flora. Above the Indian plain, the country gradually rises, stage after stage, hill after hill, from the luxurious jungle of the foothills, about 200 meters above sea level to the solitude of the snow capped peaks culminating at more than 7500 meters.

These differences in altitude, bringing almost tropical vegetation right to the base of glaciers, has made it possible for plants of extremely different climate and environments to grow in the same country. Tropical and subtropical forests are found in the south. Temperate and even Mediterranean plants flourish in the valleys, and very rare specimens grow up to 500 meters. To date, more than 600 medicinal plants have been identified in Bhutan, and at least 300 of these commonly used by practitioners for preparing drugs, pills and tablets.

The Bhutanese medical system goes well beyond the notion of medicine in the narrow Western sense. It forms part of a whole-blending culture and tradition-in which Buddhism is the prevailing influence. Health and spirituality are inseparable and together they reveal the true origins of any sickness. The art of healing is therefore a dimension of the sacred.

The system of medicine referred to as Sowa Rigpa is practiced in many countries today, but owes its origins and development to ancient Tibet. Sowa Rigpa is known nowadays as Tibetan medicine.

It is believed that the beginning of time, the art of healing was a prerogative of the gods, and it was not until Kashiraja Dewadas, an ancient Indian king, went to heaven to learn medicine from them, that it could be offered to man as a means to fight suffering. He taught his progeny the principles and the practice of healing, and this knowledge was spread and perpetuated as an oral tradition until the lord Buddha appeared and gave specific written teachings on medicine. These were recorded in Sanskrit and became part of early Buddhist sacred writings.

When Buddhism was first brought into Tibet in the eighth century by Guru Rimpoche, some of these medicinal texts were translated into the Tibetan Language, and enlightened rulers of that country became interested in the subject. They started promoting the development of the art of healing, by organizing meetings on medicine to which they invited healers not only from the whole of Tibet and surrounding Himalayan countries, but also from China, India, and the Muslim world. It is reported that all these conferences, all the different systems were examined and the best practices adopted and incorporated into the newly born Sowa Rigpa, which was then handed down from one generation to the next. This tradition was further enriched by the contribution of great Tibetan doctors including Yuthog "the Elder" in the eighth century, and one of his descendants, Yuthog "the Younger," who lived in the eleventh century. The latter made a notable contribution in spreading the celebrated Gyu'shi or "Four Medical Tantras" and its commentary, the Vaidurya Ngonpo. The Four Medical Tantras, which were originally Sanskrit texts dating perhaps from the fourteenth century, are unanimously considered to be the basic work of Tibetan medicine. It was under the reign of the fifth Dalai Lama that the Chagpori Medical School, soon to become a famous center of healing, was founded at Lhasa.

Though it took shape in Tibet, this medical tradition, which is still practiced in Bhutan, has always been characterized by the diversity of its origins. It is based on Indian and Chinese traditions and has also incorporated ancient medical practices connected with magic and religion. However, in essence, it is based on the great principles of Buddhism and provides a comprehensive way of understanding the universe, man, and his sicknesses.

Indian sources, including Ayurvedic Medicine, were the most important. They provided the majority of the theoretical bases of the medical tradition, revealed to mankind through the channel of Vedic sages. In this tradition, man can be understood by analogy with the universe, the laws and matter of which serve as a model of elementary physiology. There is thus an identity of nature between the solid parts of a man and the earth, his fluids and water, and his body heat and fire, his breath and the wind. These parallels gave birth to the theory of the humours, one of the fundamental principles of medicine now practiced in Bhutan.

Chinese sources also played a decisive role. Here again, physiology and physiopathology are based on a close relation between the human microcosm and the universal macrocosm. For Chinese philosophers and doctors, these two worlds are governed by the same law derived from an immutable and eternal principle, Tao, of which there are two aspects: yin and yang. The entire universe, including human beings, goes forward rhythmically in accordance with the yin and yang. In medical sphere, the balance or imbalance of this fundamental energy will result in health or sickness. In addition, the system of channels running through the body and enabling energy to circulate, and the distinction between full and empty organs, are both taken from China. However, the most important contribution of Chinese medicine to the art of healing is the examination of the pulse, which indicates, in particular, any disorder connected with an excess or shortage of yin and yang.

These two great systems of thought inspired Tibetan and Bhutanese medicine, but there were also local influences. In many ancient accounts, sickness is usually attributed to demonic causes. Local gods, demons, and spirits of all kings could be considered as responsible for certain illnesses. To obtain healing, it was necessary to practice particular rituals and only monks or magicians were in a position to do so. This medical practice thus involved divination, as the means of diagnosing and recognizing the spells causing the illness, and exorcism, as the way of treating the patient. And even though medical techniques in Tibet and Bhutan developed subsequently, the combination of observation, experience, study, knowledge, and popular beliefs had a definite influence in the way traditional medicine evolved in each land.

Over and above these various influences, Buddhism itself is at the heart of Tibetan and Bhutanese medical traditions. Buddhism teaches that the existence of phenomena and suffering (sickness, old age and death) have a single origin that prevents man from reaching enlightenment, namely ignorance. This is the origin of the three moral poisons, desire, aggressiveness, and mental darkness. In turn, these three moral poisons will produce the three pathogenic agents-air, bile and phlegm-which are the origin of sickness. With its overall conception of the universe and life, Buddhism is a way of linking medical theory to the same single source, in which sickness finds its natural place. Only knowledge, leading to Enlightenment, can free mankind from this painful existence.

It was only after reaching enlightenment and understanding of the ties binding man to this world, and the means of freeing himself from them, that Buddha could define the origin of pain, discover the way to eliminate it and teach an effective theory. It is therefore no surprise that he became the most outstanding healer. Through his own experience, he discovered the art of healing old age, sickness, and death. The divinity of medicine, Sangye Menla (the Medicine Buddha) is represented in traditional iconography with a blue body. His right hand holds out the Terminalia chebula, which is believed to cure all illnesses, as a gift. In his left hand is a bowl of ambrosia, the elixir of immortality.

When Shabdrung Ngawang Namgyel came to Bhutan in 1616, his Minister of Religion, Tenzing Drukey, who was also an esteemed physician, started the spread and teaching of Sowa Rigpa. Although there were sporadic instances of Bhutanese being sent by their patrons to study this art in Tibet before then, it was only after 1616 that Sowa Rigpa was established permanently in Bhutan.

Since then, the Bhutanese tradition of Sowa Rigpa has developed independently of its Tibetan origins and although the basic texts used are the same, some differences in practice make it a tradition particular to the country. The specific knowledge and experience gained by the Bhutanese over the centuries are still very much alive in this medical tradition that originated in Tibet. The natural environment, with its exceptionally rich flora, also enabled the development of a pharmacopoeia of which there is no equivalent anywhere in the world.

Unfortunately, very little is known of the traditional doctors who practiced in Bhutan from the time of Shabdrung Ngawang Namgyal (1594-1651; the founder of the Kagyu tradition of Buddhism in Bhutan) to the time of the Wangchuck Dynasty (1907-present). His Majesty Ugyen Wangchuck, the first King of this dynasty, had at his court a personal physician, Dungtsho Pemba, who was the descendant of a family of traditional doctors and whose father, Dungtsho Gyeltshen, was said to have been the personal physician to the first King's father, Jigme Namgyal.

Dungtsho Gyeltshen was trained in Tibet in the famous Lhasa Medical School of Chagpori. Dungtsho Pemba's son, Dungtsho Penjore, who also studied at Chagpori, acquired the fame of being the best doctor in the family and was called to serve at the court of His Majesty Jigme Wangchuck, the second King of Bhutan. These physicians used to send raw materials to Tibet and received the prepared drugs from Chagpori. They apparently never manufactured the medicines.

Another Bhutanese physician at the court of the second King was Mahaguru, the former Gangtey Trulku's physician. Mahaguru was from Gangtey Gompa and trained as a doctor there. He was a very saintly man as well as a good doctor, prepared his own medicines whenever he needed to prescribe them to his patients. On His Majesty's orders, he was provided with regular rations from Wangdi Phodrang Dzong.

In the first half of the 20th century, another famous physician was Dungtsho Chimi Gyeltshen. When he turned twenty, he went to Tibet to study medicine at Chagpori. After staying there for 16 years, during which he rose to the highest rank for a traditional physician, he came back to Bhutan at the bidding of Ashi Kenchock Wangmo, the second King's younger sister, and settled near Kurtoe. Dungtsho Chime Gyeltshen died in 1966.

The first practitioner to work as a government servant, in the modern sense of the word, is Dungtsho Pema Dorji (current director of the National Institute of Traditional Medicine), who opened the first government run, traditional-style dispensary in Dechencholing, Thimphu. During the first year of work at the dispensary, he was joined by Dungtsho Sherab Jorden, the former physician to Lam Namkhey Ngyingpo, at Karchu, Tibet. Shortly after that Ladakh Amchi, another physician joined the team. He has since died. These two physicians were both graduates from the other medical school at Lhasa, the Mentsekhang.

Dungtsho Pema Dorji was born in the Tongsa region of Bhutan, in the little village of Phuntsochoeling gompa. Pursuing a well-established family tradition, he began his medical studies in Kurtoe in the east of Bhutan under Dungtsho Chimi Gyeltshen, his grandmother's brother. He remained there for three years, learning the rudiments of the art of healing. In spite of a pleasant life in the Kurtoe region, he decided at the age of 16 to leave Bhutan for a while to continue his studies in Tibet, at Chagpori Monastery, one of the two famous medical schools in Lhasa [destroyed in 1959 by Chinese soldiers]. He intended to reach Lhasa via Bumthang, a feat of adventure at the time. The route took him over the terrible Melakarchung pass, which climbs to more than 5000 meters against an awesome backdrop of ice and snow. With his teacher, he crossed the higher Himalayas on foot, carrying raw materials and food and, after a month's travel, arrived safely in Lhasa, where he was dazzled the splendors of the Dalai Lama's ancestral capital. He joined the monastic body at Chagpori medical school and, in his monk's habit, spent seven years studying in Tibet with the greatest masters of the Sowa Rigpa medical tradition.

Dungtsho Pema Dorji at the age of 18 |  New Year festival Lhasa |

Recalling those years spent in Lhasa, Dungtsho Pema Dorji remembers a life devoted to study and in acquisition of knowledge, with a strict monastic discipline. However, he also recalls happy, magical moments during the great festivals of the Tibetan religious calendar. In particular, he remembers with emotion the Losar (New Year) festival, when sacred dances and horse races took place at the foot of the Potala. The celebration was followed by three weeks of rituals to mark the Monlam Chenmo (Great Prayer). On that occasion, all the monks from the monastic universities of Lhasa gathered around the Jokhang to celebrate the New Year rites. There were more than 25,000 monks from Sera, Drepung, or Ganden, thronging the streets of the Tibetan capital, transforming it into a symphony of gold and crimson.

December 2002