Finally, there is pricking of the ear apex (tubercle) to let out blood, as a similar basic technique. All these peripheral point bleeding treatments are used for heat and excess syndromes. As an example, treating the ear apex by bloodletting has been recommended to treat hordeolum, an eye infection (8).

Peripheral blood-letting is distinguished from a practice of pricking the skin to release blood prior to applying cups, that provide an additional stimulus to the area and cause more blood to be extracted. However, like the peripheral point bleeding, it is used to let out pathogens and heat. A report on treatment of acute diseases with blood-letting followed by cupping suggested that the technique would remove toxic heat from the interior (9). In general, the author believed that:

The combination of bleeding and cupping aims at eliminating the toxic factors and removing stagnation, promoting resuscitation, and clearing heat, activating qi and blood circulation in the meridians and collaterals, relieving swelling and pain in order to facilitate the elimination of pathogenic qi and the restoration of good health.

He gave examples of blood-letting and cupping at dazhui (GV-14), taiyang (Extra-2), and weizhong (BL-40). Weizhong, at the back of the knee, is probably the most frequently mentioned non-peripheral point for bleeding therapy, with or without cupping; quze (PC-3), at the corresponding point in the crease of the elbow, is next most frequently used. Dazhui (GV-14), the meeting point of all six yang channels with the governing vessel, is treated for many acute heat syndromes, with standard acupuncture, blood-letting, and cupping.

Some of the peripheral blood-letting applications are easy to understand, at least theoretically, from the basic concept of letting out tainted blood; for example, to treat a poisonous snake bite where venom has been injected into the nearby portion of the limb. Similarly, swelling and pain of the foot by letting out blood at the toes is conceptually understandable within this paradigm. The treatment of stroke (apoplexy), coma, mental dysfunctions, and epilepsy by this method may be related to the concept that a vicious wind penetrates to the center and causes severe disruption to the normal brain function; the wind turbulence generates heat in the blood; alternatively, a disease with high fever can cause these damaging sequelae. This heat may be released by causing bleeding from these points, under the concept that the blood is a vehicle for carrying out the excess heat. In the English-Chinese Encyclopedia of Practical Traditional Chinese Medicine (10) under the condition called wind-stroke, in addition to several acupuncture points to be treated by standard needling, the authors mention using a three-edged needle to cause bleeding at the jing-well points. The Encyclopedia states that "pricking the 12 jing-well points helps to eliminate heat and bring resuscitation."

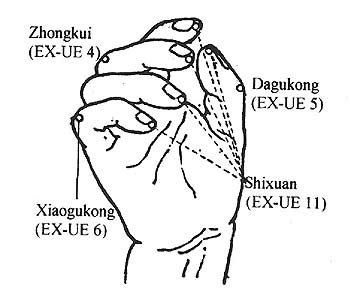

The problems of high fever, bleeding, sore throat, and headache might also be understood in terms of being treated by letting out heat via the removal of bad blood or excess blood. In the English-Chinese Encyclopedia, pricking the jing-well point shaoshang (LU-11), is mentioned as one of the treatments for severe cough due to wind-heat affecting the lungs; the jing-well point zhongchong (PC-9), as well as the non-peripheral points at the limb joints, quze (PC-3) and weizhong (BL-40), are indicated for pricking to release blood for treatment of high fever with heat in the ying and blood levels. shixuan points at the fingertips, as well as PC-3 should be pricked, the book suggests, for treatment of heat stroke (summer heat disturbing the heart and requiring resuscitation). Bleeding at the jing-well point zhongchong (PC-9) is also suggested for treatment of syncope of the excess type, while pricking of the 12 jing-well points is part of the therapy for severe sun stroke. Another recommendation for treating sunstroke is the combination of quze (PC-3), weizhong (BL-40), and dazhui (GV-14) as well as the 12 jing-well points all being pricked to cause bleeding.

MODERN VIEWS

Blood-letting is a method of therapy that is difficult to explain in modern terms. Aside from the traditional theoretical basis for these treatments in letting out heat and excess factors, a key issue is whether it actually produces the claimed effects. Many Western acupuncturists have stated informally that they get dramatic results from this treatment method, but, unfortunately, there is no evidence presented to support such contentions. Despite the frequent mention of treating peripheral points by blood-letting in both ancient and modern Chinese medical texts, there is little reference to this technique in Chinese medical journal reports. Very few articles focus specifically on use of this technique. Further, descriptions of therapies for the disorders that peripheral blood-letting is supposed to successfully treat rarely include that method. Instead, standard acupuncture techniques without blood-letting, as well as herbal therapies, are described. Therefore, the effectiveness of the technique must be questioned, at least until further evidence has accumulated.

When the method of peripheral blood-letting is used, it is usually combined with other therapies (e.g., standard acupuncture or even Western drugs) that might be sufficient to explain the claimed beneficial effects. In a report on treating hordeolum by bleeding the ear tubercle mentioned in the previous section, the eyes were also treated with antibiotics. In an article on treatment of patients with persistent hiccup (1 to 15 days) with bleeding of jing-well points, the treatment was accompanied by standard acupuncture at several points (BL-13, BL-17, BL-21, ST-44, ST-45, LI-1, and LI-4). It was reported that 95 out of 131 patients were cured after one treatment (9). It is difficult to know how much of a contribution was made by the peripheral blood-letting.

A Chinese physician who has used the blood-letting at the hand jing-well points extensively for emergency cases wrote a report on his experience (see Appendix 1). In his general analysis of treatment strategies and in two case presentations, he described use of standard acupuncture therapy, particularly needling of LI-4, along with bleeding the hand jing-well points bilaterally. It was not possible to tell whether the same results could have been attained without the blood-letting portion of the treatment. One of the claims commonly made by Western acupuncturists is that blood-letting at the jing-well points or at the ear can rapidly decrease blood pressure. Yet, in a clinical study conducted in Beijing with patients carefully monitored for responses to acupuncture therapy for hypertension, blood-letting was not a technique employed (10). The author claimed a good effect with standard acupuncture, using such points as LI-4, LI-11, GB-20, LV-3 and BL-17. In all these cases, hegu (LI-4) was needled; it is possible that this is the most effective point. Blood-letting at the ear apex was mentioned only in passing as one ear acupuncture technique in the book Traditional Chinese Treatment of Hypertension (14), but was reported to be highly effective for hypertension in a single case report (15).

Today, we know that the peripheral blood has the same content as the rest of the blood that circulates in the body, and that there is no reason to expect that the blood let out by this method is "bad blood," other than in a purely symbolic role. While standard acupuncture therapy is depicted as being effective, in part, by releasing various transmitter substances (e.g., endorphins), by stimulating local blood flow (e.g., by dilating vessels), and by producing changes in the brain that may have both systemic and highly specific effects, letting out a small amount of blood (usually just a few drops) remains without a suitable explanation for the potent effects claimed. The technique used to let out the blood is one of quick and light pricking to pierce the skin and vein. Unlike standard acupuncture, this method does not involve getting a qi reaction or other evidence that the body is responding on a deep level.

Blood-letting occurs in numerous contexts in the modern world. Millions of people donate a pint of blood, sometimes regularly; millions more prick fingertips every day to get a blood sample for diabetes testing. While these experiences are not as specific as aiming for certain acupoints to release blood, the large number of points at the periphery indicated for blood-letting in the Chinese literature, often with overlapping indications, suggests that the technique does not necessarily require a high degree of specificity for the location. Do diabetics and blood donors suffer substantially less from syndromes of heat and excess?

Therefore, acupuncturists should be somewhat cautious in making claims of effectiveness and should request clinical trials to evaluate the method, especially now that funding for acupuncture trials is being provided in the U.S. Since many of the applications of this method are for acute syndromes or disorders easily measurable, it should be possible to compare the effects of blood-letting at acupoints versus non-acupoints, or blood-letting by pricking versus pricking without releasing blood, as well as to compare standard acupuncture to blood-letting for treating a particular disorder.

SUMMARY

Blood-letting is an ancient therapy that was an essential part of traditional acupuncture practice described in the original texts and which persists today, particularly for treatment of emergency cases, such as loss of consciousness, high fever, and swellings. Most of the blood-letting therapy relies on treating peripheral points of the fingers and toes. Its purpose is to alleviate excess conditions, particularly heat syndromes and fluid swelling, and to promote resuscitation. A traditional concept was that the release of blood would draw out the excess. This therapy is somewhat difficult to explain in modern terms, and, therefore, requires some investigation and research before any substantial claims of effectiveness can be made. Practitioners often note what appear to be prompt and dramatic results from the therapy, suggesting that its efficacy should be easy to confirm using short-term trials. In most cases, peripheral blood-letting (or other blood-letting therapy) is accompanied by standard acupuncture, especially with points that are not far from the blood-letting points, such as the hand/wrist points LI-4, LU-7, and PC-6 and the foot/ankle points LV-2, LV-3, and KI-3, suggesting that these other points may contribute significantly to the observed therapeutic outcome. As a symbolic therapy-of letting out excess, bad blood, toxins, or heat-blood-letting is a potent technique for both the practitioner and the patient, and its use represents a continuation of the earliest traditions of acupuncture.

APPENDIX 1. Clinical Application of Twelve Well Points by Duan Gongbao.

The following brief report (12) was edited slightly for readability and to avoid repetition:

In many years' clinical practice, I used blood-letting method of "Twelve Well-Points" to treat emergencies such as coma, syncope, acute infantile convulsion, wind-stroke syndrome, hysteria, epilepsy, etc., and have achieved immediate results. Twelve Well-Points refer to bilateral hand well points: shaoshang (LU-11), shangyang (LI-1), zhongchong (PC-9), guanchong (TB-1), shaochong (HT-9) and shaozhe (S-I 1) which belong to the three yin and three yang meridians of the hand and are located at the finger tips. The 6 well-points of the yang meridians belong to metal and are the beginning points of the three yang meridians of the hand, while the other 6 well-points of the yin-meridians belong to wood and are the ending points of the three-yin meridians of the hand.

The indications of the Twelve Well-Points are acute febrile diseases, cerebrovascular diseases, wind-stroke syndrome, syncope, acute infantile convulsion, manic and depressive psychosis, etc. The Twelve Well-Points can be used for eliminating heat, resolving phlegm, restoring consciousness, and promoting resuscitation. It is recorded in the classic book Lingshu that psychiatric diseases are related to the five zang-organs, so, the well-points are often used. It also says that blood diseases are related to the heart, thus, blood-letting can eliminate pathogenic heat and cause resuscitation. Therefore, pricking for bleeding and twirling-reducing or twirling-pricking of the well-points can be used to treat mental disorder, excess type of wind-stroke syndrome, acute infantile convulsion resulting from attack of pericardium by heat, heart disturbed by phlegm-fire, or mental confusion due to phlegm, syncope due to high fever, etc. After routine sterilization with 75% alcohol, hold a sterilized three-edge needle to prick these well-points rapidly, then squeeze the local point forcefully to let a few drops of blood out.

When the patient falls into sudden mental changes, loss of consciousness or mental disorder, the Twelve Well-Points are treated to induce resuscitation, as follows:

- Accumulation of phlegm-heat in the lung and heart confused by phlegm: in case of invasion of the pericardium by pathogenic factors, it is treated by ventilating the lung and resolving phlegm, clearing away pathogenic heat from the heart to cause resuscitation. The 12 well-points are used in combination with chize (LU-5), shenmen (HT-7) and daling (PC-7), which are punctured and stimulated with the reducing method.

- Attack of the pericardium by pathogenic summer-heat: in case of heatstroke due to accumulation of pathogenic heat to block qi flow, it is treated by clearing away pathogenic heat from the heart to cause resuscitation, restoring the consciousness. The well-points are selected in combination with reducing shenmen (HT-7) and pricking quze (PC-3) to let a bit blood out.

- Wind-stroke: in case of excess syndrome of stroke, it is treated by clearing away heat, inducing resuscitation and waking up the patient from unconsciousness. The 12 well-points are punctured in combination with needling by the reducing method yongquan (KI-1) and hegu (LI-4).

- Interior heat-syndrome: in case of acute infantile convulsion due to high fever and wind stirring inside, it is treated by clearing away heat and toxic materials, eliminating pathogenic heat from the heart, calming the liver to stop the wind, and by using well-points combined with needling by the reducing method hegu (LI-4) and taichong (LV-3).

As an example, Mr Wang, aged 58 years, a farmer, suddenly fell into coma; he had flushed complexion, lockjaw, deviation of the eyes, rigidity of both hands, rattling sound in the throat due to phlegm, full and taut pulse. His syndrome was heart stirred by phlegm-fire, producing an excess type of wind-stroke syndrome. Therapeutic principles applied were eliminating heat, resolving phlegm, causing resuscitation, and restoring consciousness. Acupoint selection included the Twelve Well-Points pricked to let a bit of blood out; hegu (LI-4) and taichong (LV-3) were punctured and stimulated with reducing method (needles retained for 10 minutes). After treatment, the patient was restored to consciousness immediately, accompanied with slight deviation of the mouth and eyes, weakness of the upper and lower limbs on the left side. Thereafter, acupoints on the face and limbs were punctured continuously. Half a month later, he returned to normal.

As another case, a male baby, aged 2 1/2 years, experienced high fever, convulsion, lockjaw, muscular spasm of the four limbs, and loss of consciousness. Differentiation of syndromes indicated acute infantile convulsion due to excessive interior heat and wind stirring inside. Therapeutic principles applied were dispelling wind and removing heat, calming the internal wind and relieving convulsion and spasm. Acupoint selection included the Twelve Well-Points which were pricked to let a bit of blood out, combined with puncturing and stimulating hegu (LI-4), taichong (LV-3), and jiexi (ST-41) with the reducing method. After treatment, the baby was restored to consciousness immediately. Half an hour later, his fever abated and he spoke and laughed as usual.

The effects of the Twelve Well-Points in causing resuscitation, clearing away heat from the heart and tranquilizing the spirit, ventilating the lung, and regulating yin and yang are derived mainly from the combined application of the Three Yin and Three Yang Meridians of the hand. Shaoshang (LU-11) and shangyang (LI-1) serve to ventilate the lung, remove heat from the throat, regulate the wei qi to relieve the exterior syndrome, and reduce fever. Zhongchong (PC-9) can function in clearing away heart-fire and accumulated heat of the pericardium, tranquilizing, inducing resuscitation and restoring consciousness. Guanchong (TB-1) can clear away the pathogenic fire of the upper-jiao and remove the accumulated heat in the shaoyang meridian. Shaochong (HT-9) is used to clear away heart fire, tranquilize, and regulate heart qi. Shaozhe (SI-1) serves to remove heart fire, ease mental anxiety, and eliminate accumulation of heat in the taiyang meridian. The aforementioned acupoints are only suitable for recuperating depleted yang and rescuing the patient from collapse, rather than for prostration (deficiency) syndrome due to sudden exhaustion of yang of emergence or due to exhaustion of qi from chronic disease because of excessive weakness of the primordial qi. Therefore, the Twelve Well-Points should be used according to differentiation of syndromes. Otherwise, erroneous application of these acupoints will bring the patient with unfavorable influence and even miss the opportunity for emergency treatment because of delay.

APPENDIX 2. Clinical Application of Blood-Letting Therapy by Yang Haixia

The following report (15) includes the full text of the physician's instructions on treatment, and then his case reports, which are shortened considerably for presentation here.

The operator needs to massage the determined area for blood-letting to cause local congestion, and clean the skin area for disinfection according to the routine procedure. Fix the acupuncture point or vein in the blood-letting area with one hand, and hold a sterilized three-edged needle with the other hand to prick the point or vein 1-3 mm deep quickly and then remove the needle immediately. Press and squeeze the muscle around the pricked point or vein to cause bleeding. The amount of bleeding caused for each treatment varies from a few drops to several milliliters of blood according to the individual cases, the areas for blood-letting, and the patients' conditions. Clinical practice has proved that this therapy has the functions of inducing resuscitation, reducing heat, invigorating blood, removing stagnation and obstruction in the channels, and can be mainly applied to treat excess, heat, and acute syndromes.

Case 1. Chronic headache caused by hyperactivity of yang. Extra points taiyang and yintang were pricked to let out a few drops of blood. Shortly after treatment, the pain disappeared suddenly, without relapse.

Case 2. Apparent small stroke, causing sudden deviation of mouth, left eye being closed, and chewing dysfunction. An obviously distended vein in the mouth was pricked to cause bleeding, once per week. Body acupuncture with electric stimulation was used additionally, every other day. After 30 days treatment, facial muscles returned to near normal.

Case 3. Apparent small stroke with rigidity, pain, and numbness of tongue accompanied by dysphasia. Extra points jinjin and yuye of the lingual vein were pricked for bleeding. Two treatments resolved the disorder.

Case 4. Intermittent dizziness, tinnitus, and heaviness of the head due to hypertension. Blood-letting was done on the ear apex on both sides and the groove on the back of the ears to let out a few drops of blood. After five treatments, the blood pressure was stabilized at a lower level with relief of symptoms.

APPENDIX 3. Summary of Major Blood-Letting Points

The following tables are derived from the Advanced Textbook on Traditional Chinese Medicine and Pharmacology (13).

Summary of Peripheral Points for Blood-Letting

This table does not include the jing-well points, which are manly used for the same indications as the other points listed here, except for the unique pediatric therapy of the sifeng points.

| Point Name | Distribution of Blood Vessels | Indications |

| shixuan | at the fingertips, network of the proper palmar digital arteries and veins | fever, coma, sunstroke, unconsciousness, numbness of the hands and feet |

| Shierjing | behind the corner of the fingernails, network of the proper palmar digital arteries and veins | fever, coma, sore throat, tonsillitis |

| sifeng | network of the proper palmar digital arteries and veins | infantile malnutrition, dyspepsia, pertussis (squeeze out yellowish-white fluid) |

| Yuji (LU-10) | reflux branch of the cephalic vein in the thumb | fever, sore throat, tonsillitis |

| Bafeng and qiduan | dorsal venous network of the foot | swelling, pain and numbness of the foot, snakebite |

| baxie | dorsal subcutaneous network of hand | swelling, pain and numbness of the hand, snakebite |

| Ear apex, supratragic apex, and earback | posterior auricular artery and vein | fever, tonsillitis, red and swollen eyes, hypertension |

Summary of Body Points for Blood-letting

This table does not include the point dazhui (GV-14), which is also often used in blood-letting, especially accompanied by cupping. Dazhui has he indications of treating various heat syndromes and fevers, and epilepsy.

| Point Name | Distribution of Blood Vessels | Indications |

| Chizi (LU-5) | cephalic vein | sunstroke, acute vomiting and diarrhea |

| Quze (PC-3) | cephalic vein | sunstroke, suffocating feeling in the chest, fidgets |

| Weizhong (BL-40) | great and small saphenous veins of the popliteal fossa | sunstroke, acute vomiting and diarrhea, systremma |

| Yintang | branches of the medial frontal artery and vein | headache, dizziness, red and swollen eyes, rhinitis |

| Taiyang | venous plexus inside temporal fascia | headache, red and swollen eyes |

| Baihui (GV-20) | anastomotic network of the left and right superficial temporal artery and vein and occipital artery and vein | fever, tonsillitis, red and swollen eyes, hypertension |

| jinjin and yuye | lingual vein | apoplexy, stiff tongue, and stuttering |

REFERENCES

- Ellis A, Wiseman N, and Boss K, Fundamentals of Chinese Acupuncture, 1988 Paradigm Publications, Brookline, MA.

- Unschuld P, Medicine in China: A History of Ideas, 1985 University of California Press, Berkeley, CA

- Wu jingnuan (translator), Ling Shu or The Spiritual Pivot, 1993 The Taoist Center, Washington DC.

- Ni Maoshing (translator), The Yellow Emperor's Classic of Medicine, 1995 Shambhala Publications, Boston, MA

- Yang Shouzhong and Chace C, The Systematic Classic of Acupuncture and Moxibustion , 1994 Blue Poppy Press, Boulder, CO.

- Anonymous, Essentials of Chinese Acupuncture, 1980 Foreign Languages Press, Beijing.

- Long Zhixian (general chief editor), Acupuncture and Moxibustion, 1999 Academy Press, Beijing.

- Wang Zhao, Wan Xiaosong, and Zhang Qiuying, Treatment of hordeolum by blood-letting at ear apex, Journal of Traditional Chinese Medicine 2001; 21(3): 213-214.

- Yin Ying, Blood-letting at a single point for treatment of acute diseases, Journal of Traditional Chinese Medicine 1997; 17 (3): 214-216.

- Xu Xiangcai (chief editor.), The English-Chinese Encyclopedia of Practical Traditional Chinese Medicine, (volume 6) 1989 Higher Education Press, Beijing.

- Tian J, Acupuncture treatment of 135 cases with hiccup, World Journal of Acupuncture and Moxibustion 1999; 9(l):54-55.

- Duang Gongbao, Clinical application of twelve well points in emergency treatment, World Journal of Acupuncture and Moxibustion 2000; 10(2).

- State Administration of Traditional Chinese Medicine and Pharmacy, Advanced Textbook on Traditional Chinese Medicine and Pharmacology, volume 4, 1997 New World Press, Beijing.

- Hou jinglun, Traditional Chinese Treatment for Hypertension, 1995 Academy Press, Beijing.

- Yang Haixia, Clinical application of blood-letting therapy, Journal of Traditional Chinese Medicine 2002; 22 (1): 26-28.

August 2002

Figure 1: The nine original acupuncture needles.