Figure 1: The enormous ginkgo tree at

the Cave of the Heavenly Teacher.

GINKGO

So eulogized the poet Li Shanji about the ginkgo tree, during the 19th century, while visiting sacred Mount Qingcheng in the foothills of the great mountain range leading from Sichuan Province to Tibet (1).

Today, the ginkgo tree is deemed to be biologically the oldest tree in the world, a "living fossil" from earlier evolutionary history (2). The genus dates back to 165 million years in China. Most of the trees, accustomed from the beginning to moderate climate to which they took all across the northern hemisphere, were destroyed by the ice age, with surviving members left only in the Orient. Individual ginkgo trees also compete for the title of oldest living specimens of life on earth. Surveys done in China have revealed that there are some ginkgo trees that are as much as 3,000 years old, with a total of about 180 trees exceeding 500 years of age (3). The largest grove of old ginkgos is in the Tian Mu Shan (Heaven's Eyes Mountain) Nature Reserve in Jiangsu Province.

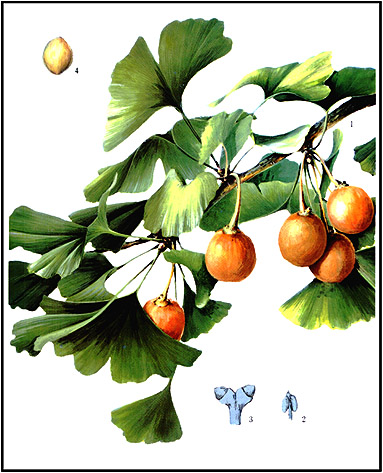

One of the most famous ginkgo trees now standing is said to have been planted by Zhang Daoling, later called the Heavenly Teacher, who practiced the Oriental arts of spiritual alchemy and shamanism. On Mount Qingcheng, where he lived as a hermit, he turned his cave into a center of an organized religion in 143 A.D., with the tree at its side. Over the centuries, the tree became incorporated into the structure of the Cave of the Heavenly Teacher, a popular pilgrimage site. This imposing ginkgo tree (see Figure 1) has grown to a height of more than 50 meters (about 160 feet), with a circumference of 7 meters (about 22 feet). The tree's stature is further enhanced by numerous "roots" that appear like stalactites hanging from the branches. These arose from falling ginkgo nuts that had landed on the tree and grown in place. It is this tree that inspired Li Shanji.

The Chinese people have known the ginkgo tree for its prominent fruits, calling it the Silver Almond Tree or the White Nut Tree. The tree has also been known for its peculiar fan-shaped leaves, something like duck feet, and hence called the Duck Feet Tree. It has been revered as a sacred plant: named the Ancestor Tree, Buddha's Fingernail Tree, and Eyes of the Cosmic Spirit Tree. Since the 10th Century A.D., the name Silver Almond Tree (yinxing) has been most often used to refer to it, probably because of the importance the tree's almond-shaped nut gained as a food. At that time, it was declared a tributary item offered to the Imperial Court, to be used in the Emperor's banquets.

It has been reported that the first Westerner to bring back a description of the ginkgo tree was a German surgeon employed by the Dutch East India Company, visiting Japan around 1700 A.D. (4). Dutch traders visiting Japan soon brought ginkgo trees to Europe in 1727. There, it gained the common name Maidenhair Tree, because the leaf resembled that of the local maidenhair fern. Ginkgos were planted in the famous Kew Gardens in 1754, where they still stand as relatively young specimens at 250 years old.

The botanical name we use was assigned by the famous botanist Linnaeus in 1771. It arose from the mixing of the Chinese names for Silver Almond and White Nut by the Japanese, yielding yinguo (silver nut), which the Japanese pronounced roughly as ginkgo. The leaves form two lobes, hence the species name biloba. The tree was introduced to America in 1784 and soon became a popular curiosity in the Northeastern U.S. Today, ginkgos are widely used as ornamental trees, especially in cities, where they survive well amongst the pollution and poor soil, throughout much of North America and Europe.

The worldwide interest in ginkgo that exists today stems from this tree's potential medical applications, well-known where ginkgo originated but not recognized here until more than 250 years after the tree was introduced. The Chinese may have begun their medicinal use of the tree with the nuts, as the practice of finding medicine among foods is common there, but they soon added the leaves and even the roots to their list of valuable medicinal materials. The leaves were the plant part first put into practical use in the Western world, in Germany during the past decade.

According to the European research, which now includes over 300 published articles on the chemistry, pharmacology, and clinical applications of ginkgo, the leaves contain substances that promote blood circulation, alleviate allergy reactions, and have antioxidant properties. Probably the most dramatic claim is that it helps improve circulation to the brain and alleviates memory problems that are characteristic of Alzheimer's Disease and other forms of dementia.

What is the origin of this finding, which has garnered so much attention that it may have the broader impact of helping to restore herbal medicine to a prominent place at the end of the 20th century?

In 1330, the work of the officially appointed medical authority Wu Rui was written under the title Materia Medica for Daily Use (Riyong Bencao). This book detailed the medicinal properties of 540 items that could be used both as food and medicine, including the ginkgo nut. This item was a local favorite, as Wu lived near the Tian Mu Shan grove (he may have obtained ginkgo nuts from trees that still thrive there). The Materia Medica was handed down through generations of Wu's family and was finally published around 1550.

The medicinal uses of ginkgo nut were mainly involved with treatment of lung diseases. In fact, one of the famous traditional Chinese formulas for treating asthmatic breathing, Ding Chuan Tang, has ginkgo nut as a key ingredient (the original formula is sometimes called Ma-huang and Ginkgo Combination as an English designation, recognizing two of its most important ingredients). The nine ingredient decoction was first recorded in the book Exquisite Formulas for Fostering Longevity (Fu Shou Jing Fang), written by Wu Min in 1530 A.D. (5). New versions of Ding Chuan Tang are sometimes developed for clinical use, with ginkgo nut as a prominent ingredient.

The fruit extract has been shown to strongly inhibit Mycobacterium, which is the cause of tuberculosis, one of the dominant lung ailments that has persisted in China. As has been confirmed by recent work in Germany, ginkgo contains ingredients that alleviate asthma. These ingredients, obtained from the leaf in Germany, are also present in the nuts.

Another traditional use of the ginkgo nut in China is as an astringent to treat fluid discharges. A remedy for leukorrhea is black chicken stewed with ginkgo nut and lotus seed (Baiguo Lianzi Dun Wuji). It is made by putting the herbal ingredients plus rice and black pepper in the unique black-boned chicken as a stuffing, cooking it, and then eating the combination (6). The recipe was recorded in Li Shizhen's Collection of Simple Prescriptions (Binhu Jijian Fang, ca. 1580 A.D.; Binhu is an alternate name for Shizhen).

Lan Mao, another Chinese herb specialist, had the first published description of medical use of ginkgo leaf in his book Dian Nan Bencao (Herbal Dictionary of Yunnan), published in 1436 A.D. He recommended topical applications of ginkgo leaf for the treatment of skin diseases.

Information about ingestion of ginkgo leaf was incorporated into a formal medical work, Compilation of Essential Items of Materia Medica in 1505. Qiu Jun, its author, specifically aimed to incorporate into his book items that had been used widely but had failed to be recorded in the previous official Materia Medicas. The book came into the hands of Liu Wentai at the Imperial Medical Office, but the work was not published until two hundred years later, and then it was all but lost, until it was recently published in 1937. After the Chinese communist revolution, the book was again all but lost. Partly as a result of this uneven path of publication, ginkgo leaf remained a folk remedy, rather than a major part of Chinese medical practice, until recently. Liu's book included a remedy for diarrhea which was made by combining ginkgo leaf powder and flour to make a bread. One of the folk remedies of more recent times is Liangye Yijiang Tang, made with ginkgo leaf, artemisia leaf, and fresh ginger, used for treating chronic bronchitis.

Modern research on ginkgo began with chemical analysis of its active constituents in Japan during the 1920's (7, 8). The ginkgo nut contains a toxic material in the seed coat, which is stripped away when preparing it for food use, but may be retained for some medical uses. The toxic component, called ginkgotoxin, was apparently the first item investigated.

The modern work with flavonoids, the components that affect circulation in the brain, was initiated by the isolation of ginkgetin, first published by a Japanese researcher in a German journal in 1932. Additional work on isolating numerous active constituents was reported by Japanese researchers during the 1950's and thereafter, with efforts continuing to the present. One of the first Western reports of active constituents (independent of Oriental study efforts) was published in 1959 in Proceedings of the Chemical Society. However, the isolated ingredients described there were the same as those reported earlier. Virtually all these chemical investigations were done with the ginkgo leaves.

Pharmacological investigation (mainly laboratory animal studies and test tube evaluations) of ginkgo's active constituents were reported soon after the constituents were isolated. In 1930, a Japanese researcher reported on the effect of ginkgotoxin on isolated frog heart; in the same year he also reported on skin irritation caused by the extract of the whole ginkgo fruit, possibly because of his own experience of that problem. In 1950, Chinese researchers reported that the ginkgo nut and its isolated active constituents could inhibit various bacteria, including Mycobacterium, and other human and animal pathogens. European pharmacological research into ginkgo started with work that resulted in a 1966 German publication reviewing the vascular pharmacology of the herb, which was then followed up by a continual line of research to the present (9).

Clinical studies (human trials) with ginkgo began during the 1960's in China with studies of the leaf extract in treatment of cardiovascular diseases, an application that had been suggested by folk uses of the herb. One of the first of several reports on this subject was issued by the Beijing Coordinating Research Group on Coronary Diseases in 1971. Research on ginkgo for cardiovascular diseases was intensively pursued during the next ten years and has continued to the present. Applications of ginkgo in China include angina pectoris, heart attack, cerebrovascular spasm, and stroke; it is also used to alleviate high cholesterol levels and high blood pressure. Other studies demonstrated benefits of ginkgo leaf in treating chronic bronchitis, Parkinson's disease, and schizophrenia.

The standardized extract of ginkgo was first introduced as a therapeutic agent in Europe in 1975 (10). European clinical trials with ginkgo were reported in Germany in 1984 and 1985 (though some preliminary experience was already accumulated before then). This research involved peripheral arterial occlusion, psycho-pharmacological effects, and hypoxia protective effects. In a major meeting on flavonoids held in New York in 1985 (11) interest in ginkgo was not yet evident: there were no reports on this very recent finding, even though there were European reports on other important flavonoids that promote circulation. But, there was a symposium on ginkgo's effects on cerebral circulation in Germany the same year. Just 12 years later, in November 1997, an article appeared in the Journal of the American Medical Association (JAMA) describing a double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of ginkgo leaf extract in treating Alzheimer's disease (12).

What got ginkgo leaf into the mainstream of research was the investment by European pharmaceutical companies (a consortium of French and German manufacturers) who developed a standardized concentrated extract of ginkgo leaf given to researchers for testing and marketed to doctors. This product has since become the number one medicinal herbal remedy sold in Germany. A substantial amount of the ginkgo leaves now come from America: there is a 1,000 acre ginkgo plantation in South Carolina. The trees are stripped of leaves at the end of June, and then the leaves are dried and shipped to France for extraction (13).

A common standardization of the extract is a finished product that contains 24% ginkgo flavonoids (known as ginkgolides; they are glycosides of commonly occurring plant flavones). To attain this level of active ingredients requires concentrating them by about 25 times their natural levels. Frequently, but not always, a product of similar standardization is sold today in health food stores in America. With all the publicity, numerous ginkgo products have been offered, from simple powdered leaves, to highly purified active ingredients with nearly 30% flavonoid levels.

This story about ginkgo briefly traces a traditional herbal remedy from an early point in its history, over 600 years ago, to the present time where it has been accepted as a plant drug in Germany and is on the verge of broader acceptance in the U.S., thanks to formal publication of clinical results in JAMA. Over the course of so many centuries, a remedy of potential value to millions has finally been raised out of the obscurity that has fettered foreign traditional medical systems for far too long.

Although the earliest visitors to China, such as Marco Polo (at the end of the 13th century), may have been awed by the civilization of China and its potential contributions to the West, during the past three centuries, Western visitors to China frequently attempted to write-off any of the cultural contributions the Chinese could make and attempted to impose its system of thought, including medicine, on China. It took Japanese researchers who published their results in the German scientific press to reveal something of what Chinese herbal medicine could offer from this plant (there is a similar story surrounding ma-huang, the source of the drugs ephedrine and psuedoephedrine). It then took a decade of German chemical, pharmacological, and clinical investigation-helped forward by the investment of a pharmaceutical consortium-to generate some interest in this valuable herb in Europe and then in the U.S. The German research post-dated similar Chinese research and made little reference to the Chinese experience and research efforts.

Perhaps as a lesson from this, we may be more open to learning from the Oriental traditional medicine and more willing to work quickly to bring forward the vast knowledge and experience of Chinese and Japanese doctors and researchers to practical applications here.

Another important lesson comes from the desire to actually use the herb once its value has been widely recognized: there may not be enough trees to satisfy world demand for the extract. Trees can be cultivated, but that takes years. Currently, about 70% of the world's ginkgo trees are in China, mainly those cultivated in Jiangsu Province in huge, dense plantations. China has recently become a supplier of ginkgo extract to America, providing an alternative to the French product that, perhaps ironically, gets its ginkgo leaves from America at higher cost.

In the case of ginkgo, there are no wild trees remaining, with the possible exception of some of the most ancient ones which might have been left in their original place. Without a wild population, the genetic diversity, and the accompanying diversity of phytochemicals, can become severely limited over time, making further medicinal developments from the plant more difficult. Therefore, it is best to uncover potentially valuable herbs early, and develop the natural resources in a timely manner, rather than waiting to the last possible moment to accept a natural remedy and then rapidly overburden the supply.

The Chinese did not know until recently the evolutionary age of ginkgo, but they could, just by contemplating its form and development, see that it was unique among trees. They knew, since ancient times, that there were male and female trees that needed to be planted nearby in order to produce seeds; further, they bloomed at night, and shed the blossoms promptly, as if celebrating the wonder of life in secret. In the famous herbal of Li Shizhen (Bencao Gang Mu, 1596 A.D.), he notes: "If one drills a hole into the side of a female ginkgo and inserts a branch from the male ginkgo, the tree will generate seeds-does this not illustrate the marvelous workings that result from attraction of yin and yang?" Temples were built next to ginkgo trees as extensions of worship of the tree itself.

Then, there is the strange appearance of stalactites (zhongru), which sometimes appear like breasts. One ginkgo in Sendai, Japan, is said to have been planted over the grave of an emperor's wet nurse, who vowed to Buddha that she would give milk to all women who had none for their babies. The tree flourished and grew great "breasts" and any woman who prays to it is said to be able to nurse her infants.

The old age attained by the trees, which would have been especially evident in ancient times before most of the forests were cleared, implied that the tree had a mystical power associated with the great spirits. Li Shizhen reported that "Daoist shamans used to engrave their magical spells and seals on ginkgo wood from old trees in order to communicate with the spirit world."

Although a focus of attention has been on brain circulation, the extracts of ginkgo have also been shown effective for peripheral arterial occlusion (affects the legs) and for angina pectoris and heart attack (affecting the main cardiac arteries and the heart). The mechanisms of action for all these include inhibiting platelet activating factor (PAF, which leads to clotting of blood), antioxidant activity (which helps to prevent further development of atheromas), and alleviating spasms of the muscles surrounding the vessels (by inhibiting nitric oxide and increasing release of endothelium-derived relaxing factor and prostcylin). PAF is released from cell membranes and causes inflammation and allergy type reactions, as well as platelet sticking.

The pharmacological effects of administering ginkgo extract include: reduces accumulation of harmful metabolites of respiration (lactates and carbon dioxide), enhances glucose uptake and normalizes cellular respiration (to maintain cellular energy metabolism), improves vascular tone, and reduces cerebral edema.

Clinical trials have reportedly found positive influence of ginkgo on vertigo, hearing disturbances, macular degeneration, and depression (14, 15). However, the quality of clinical trials has been variable. In a 1992 review of 40 papers reporting on clinical efficacy of ginkgo extract, most of them carried out in Germany and France, 8 were found to be well-designed and conducted with randomized placebo control. Since that time, the frequency of studies with good quality has increased and one can expect further work on sensory phenomena (hearing, sight, balance, perhaps also smell), psychological disturbances (depression, schizophrenia), and other applications.

The clinically effective dosage of the standardized commercial extract is about 120-240 mg/day. Treatment time of 4-6 weeks is considered a minimum duration to observe improvements, with 3-6 months as a standard course of treatment for existing symptomatic disease (6 months is usually the maximum duration of a clinical trial; longer term use may be necessary to maintain the desired effects). Higher dosages, up to 600 mg, were used to evaluate immediate effects on short-term memory, with positive results. It is not known whether such high dosages would be safe for daily use over a period of several months. The standard dosages of ginkgo extract do not cause adverse effects, except that a few people report mild gastric disturbance or headache.

While ginkgo has been made popular as a result of commercial investments in preparing extracts and sponsoring research, similar activities are attained from other Chinese herbs that have not yet been developed in the same way. For example, cerebral circulation is improved with the flavonoids from pueraria (kudzu), used in a similar dosage range.

December 1997