George Soulié de Morant |  Commemoration image for Soulié de Morant. |

CHINESE MEDICINE IN ITALY

Integrated into the Modern Medical System

Italy has a long history of interaction with China. Two famous early Italian visitors to China were the Venetian Marco Polo (1254-1324) and the Jesuit priest from Macerata, Matteo Ricci (1552-1610). Chinese medicine made its way to Italy later, primarily via its development in France during the 20th Century (for the history of the first two centuries of European developments, from 1671-1871, see Appendix 1).

Acupuncture, as a medical practice rather than a curiosity, was brought to France though the efforts of George Soulié de Morant, who was engaged in the French diplomatic service in China between 1901 and 1917. Soulié de Morant published articles and French translations of Chinese and Japanese medical texts, and on his return to France taught clinical applications of acupuncture to French physicians. He also systematically introduced acupuncture theory from the classical texts to them (see Appendix 2 for a more complete story of his contributions). A unique approach to acupuncture therapy was developed by the French proponents, which has come to be known as "French Energetic Acupuncture." Among its basic principles is the concept, common in the Chinese system, that diseases and symptoms (particularly pain) are related to blockages in the flow of qi. With this as a point of emphasis, there is a high reliance on acupuncture points that were designated as "barrier points" (see Appendix 3 for a brief review of the diagnostic approach and point selection). This system developed within the medical community, so it has primarily influenced medical doctors who practice Chinese medicine, including those in Italy and the U.S.

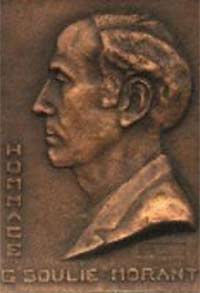

A student of Soulié de Morant, Dr. Albert Chamfrault, helped establish the French Association of Acupuncture (Association Francaise d'Acupuncture; AFA) in 1945. By 1966 this association had set up six teaching centers in France (in Paris, Bordeaux, Limoges, Nice, Strasbourg, and Toulouse). With the establishment of formal teaching opportunities, a few doctors from Italy studied acupuncture in France during the latter 1960s, and then returned to found the Società Italiana Di Agopuntura (SIA; Italian Society for Acupuncture; www.sia-mtc.it) in 1968, one of numerous professional organizations that arose in Europe since that time (see Appendix 4 for a list of several of these). This Italian society has produced numerous workshops and congresses and a journal (now in its 25th year, with quarterly publication; see article abstract and cover copy, Appendices 5, 6). Several schools of acupuncture were developed in Italy (there are at least 16 at present), one of the largest being So-Wen (Scuola di Medicina Naturale; School of Natural Medicine) in Milan, which opened its doors in 1973. The schools originally simply taught the French Energetic Method.

During the 1980s, when China had become more open to foreign visitors, new contacts with mainland China were developed by several SIA members, revealing the more complete system of Chinese acupuncture, as well as the extensive system of herbal medicine, which had not been previously introduced in Italy (or France to any extent). While French Energetic Acupuncture relies mostly on the systematic study of the meridians, Chinese herb therapies rely more on zangfu theory. It took several years to introduce and develop the zangfu framework in the Italian schools. So-Wen and a few other advanced schools quickly turned to teaching this subject; Dr. Grazia Rotolo and Dr. Caterina Martucci (authors of Farmacoterapia Cinese), introduced the first herbal seminars as early as 1987. Still, up to late 1990s most students of Chinese medicine in Italy were not able to understand and apply herbal medicine. This has changed in the past five years. Presently, 80% of the schools have adopted a Chinese program that includes both acupuncture and herbs according to the full TCM system. Roberto Gatto (president of the SIA), Sonia Benassi (head of Lao Dan, an herb company), and a few other doctors who had visited China and attended many international seminars, continue to develop and promote the TCM system, including herbal prescribing.

Aside from SIA, other organizations were established. For example, the Italian Association of Acupuncture-Moxibustion and Traditional Chinese Medicine (Associazione Italiana di Agopuntura-moxibustione e Medicina Tradizionale Cinese; AIAM) was established in 1987 with three central committees: scientific, educational, and legislative; it also incorporates the Inter-University Commission for Acupuncture Research. Additionally, there is an Italian Medical Association of Acupuncture (AMIA) in Rome and the Matteo Ricci Foundation (Fondazioni Matteo Ricci) that includes a school in Bologna, a journal, and several workshops. There are a sufficient number of acupuncture organizations in Italy that a coordinating organization was established: the Italian Federation of Acupuncture Societies (Federazione Italiana delle Società di Agopuntura; FISA) with 2,500 members. A plethora of schools and professional organizations have arisen in other European countries as well and a coordinating organization was established, called EuroTCM.

According to the Italian law, acupuncture therapy must be performed only by medical doctors (this has also been the case in France, Belgium, Denmark, and the Scandinavian countries). The So-Wen data base of MD acupuncturists, the largest file available in Italy, counts more than 7,000 names. The total number of Italian MDs trained in acupuncture is likely to be about 10,000. As in France, this represents one of the highest densities of Chinese medical practitioners outside East Asia (Holland, which does not restrict acupuncture to medical doctors, has the highest density, with an estimated one practitioner for every 3,200 people). The population of Italy is about 56 million, or less than one-fifth that of the U.S., which has a more liberal legal status for acupuncture yet has only about 15,000 licensed acupuncturists and about 5,000 medical acupuncturists. It has been reported that about 16% of Italy's population uses various types of alternative medicine, including Chinese medicine; many would like to see these covered by national health insurance.

The study of acupuncture in Italy involves 400-500 hours of training over a four year period. Since the students are medical doctors already in practice, they can only attend some weekend seminars, which accounts for the long total duration of the courses. The cost of the program is about 5,000 Euros ($6,000 U.S. at this time). The Italian programs provide about twice the training that medical acupuncturists receive in the U.S. at the main training center at UCLA School of Medicine (where French acupuncture has been a major theme). Chinese herbal medicine has been treated as an independent course in Italy (about 250-300 hours in 2 years) that is taken by some doctors after their graduation from acupuncture studies. Since the duration of training is so long (six years with the added herb courses), most students do not pursue herbal training.

Many of the acupuncturists are family doctors (general practitioners) who still rely on use of modern drug therapies. They have pursued acupuncture studies because of their concerns about drug side effects and the desire to find alternatives to the less than adequate drug therapies. A few of the doctors add Western herbs or homeopathic remedies to their prescription range; now several hundred have added Chinese herb prescribing.

In Italy, there is a limited selection of herb products (and other natural supplements) sold in stores or via the internet as non-prescription items. These do not have a good reputation among the medical doctors. The doctors would prefer to prescribe specific remedies, including Chinese herbs, based on their diagnostic work. However, by Italian law, medical doctors are not allowed to sell or give any prescription (drugs or herbs) directly to the patient; thus, they must refer the patients to a pharmacy that will carry the appropriate herbal products. Unfortunately, among the Chinese herb products that were initially introduced to Italy the quality was often poor, and there have been concerns about contamination of those coming from China. Because the term "herbal therapy" in Italy (and throughout Europe) means use of only plants, some have argued against inclusion of any of the traditional minerals and animals as commonly found in many Chinese products. The concern for high quality products coupled with the small number of prescribers has resulted in expensive products. All these factors have restricted the use of Chinese herbs in Italy. As a result, many Italian acupuncturists just apply acupuncture to treat pain and some acute symptoms, but do not deal with internal medicine (herbal medicine). Research has focused on acupuncture therapy.

Things are gradually changing in this regard; the introduction of Chinese herb courses (involving about 500 doctors) has stimulated greater interest in prescribing herbal remedies. A small herbal company in Milan, Lao Dan, began developing a product line in 1988 that has expanded to include over 30 traditional formulas relying solely on plant materials, with herb extraction carried out in Italy to assure quality (see Appendix 6 for sample label image). That company specifically aims its efforts toward assuring high quality of raw materials and manufacturing, correct formulation, and proper distribution. Due to low levels of demand at this time, it is difficult for the company to develop a full line of products, partly because all sales must go through pharmacies; it is estimated that only about 400 medical acupuncturists are routinely prescribing these items. Other small product lines have also appeared in Italy during the past few years, including a line of topical and internal remedies with a focus on orthopedics and traumatology (especially sports applications), developed by Dr. Karl Zippelius, who immigrated to Florence, Italy from Germany after studying acupuncture and herbs there. The products include pastes, salves, tinctures, and tablets.

The new programs of herbal medicine education have the capability in the next three years to train about 500 new practitioners. In addition, through seminars, as many as 1,000 current practitioners could receive continuing education on the topics. However, it is unlikely that these participation levels will be met; the actual attendance may be only 20-30% of the potential audience due to scheduling conflicts and concerns about the ability to readily obtain and utilize the herbal remedies. Perhaps with positive response to the therapies the demand for training will increase in the coming decade.

Prior to the work of George Soulié de Morant, a few Westerners had described acupuncture therapy and some had used it, but they failed to generate sufficient interest for the field to develop formally. The first records date back to 1671, when a French Jesuit priest named Harviell, who had served in China, published Les secrets de la Medicine des Chinois (Secrets of Chinese Medicine). There was brief mention of acupuncture from time to time after that, but then a number of articles and books appeared in the 19th century, outlined in the table below (adapted from Understanding Acupuncture by Birch and Felt, 1999 Churchill-Livingstone).

Some 19th Century References to Acupuncture in the West

| Date | Country | Author(s) | Nature of publication |

| 1802 | England | W. Coley | Article about the uses of acupuncture |

| 1816 | France | L. Berlioz | Book on acupuncture for chronic disorders |

| 1820 | Italy | S. Bozetti | Book on acupuncture |

| 1821 | England | J.M. Churchill | Article on use of acupuncture in treating rheumatism |

| 1822 | USA | Anonymous | Medical journal commentary favorable to acupuncture |

| 1825 | France | J.B. Sarlandiere | Article on the use of electroacupuncture for gout |

| 1825 | Italy | A. Carraro | Article on uses of acupuncture |

| 1826 | USA | F. Bache | Article about uses of acupuncture |

| 1826 | England | D. Wandsworth | Article about using acupuncture for pain relief |

| 1826 | Germany | G.E. Woorst | Review article on status of acupuncture |

| 1827 | England | J. Elliotson | Article about acupuncture for rheumatism |

| 1828 | Germany | J. Bernstein | Article about acupuncture for rheumatism |

| 1828 | Germany | L.H.A. Lohmayer | Article about acupuncture for rheumatism |

| 1828 | France | J. Cloquet, T.M. Dantu | Book on acupuncture |

| 1833 | USA | W.M. Lee | Article about acupuncture for rheumatism |

| 1834 | Italy | F.S. da Camin | Described Sarlandier's work on electroacupuncture |

| 1871 | England | T.P. Teale | Article about acupuncture for pain relief |

Peter Eckman, in his book In the Footsteps of the Yellow Emperor, presents the results of his intensive research into the development of acupuncture therapy in Europe. The main purpose of his effort was to discover the influences on J.R. Worsley, who became a significant figure in the development of acupuncture in England and America, two countries where Eckman has lived and worked. He was able to trace significant influence from both Japan (via visiting Japanese practitioners and teachers) and from China (mainly via George Soulié de Morant), as well as some influence from Vietnam and Korea, and then the interaction with German naturopathy and homeopathy. Regarding George Soulié de Morant, he wrote the following (slightly edited for presentation here):

I think we can say that contemporary traditional acupuncture in the West started with George Soulié de Morant (1878-1955) in 1927 in France. Prior to that date, there had been scattered accounts and even some books about acupuncture in Western languages, but no attempt to formulate a systematic understanding of acupuncture based on points, meridians, the circulation of qi and its management and reflection in pulse diagnosis. Soulié de Morant grew up in an unusual family that encouraged him to learn Chinese from the age of eight. He was originally schooled by the Jesuits and intended to study medicine, but had to give up that ambition when his father died.

George Soulié de Morant |  Commemoration image for Soulié de Morant. |

At 21 (1899), based on his linguistic skills, he got a secretarial job in China, and happened to be in Beijing during a cholera epidemic. Soulié de Morant became acquainted with a Dr. Yang, who was considered extraordinarily successful in treating cholera victims with acupuncture (typical formula of points: ST-25, ST-36, LI-10, and points surrounding CV-8). Soulié de Morant's curiosity was piqued to the point that he began studying with Dr. Yang, who let him do some of the treatments under his guidance.

Soulié de Morant was subsequently appointed to the French Consular Corps and sent to various cities in China, in each of which he sought out acupuncture teachers, including several in Yunnan, which is contiguous with Indochina. It is likely that the initial Vietnamese influence on French acupuncture was a consequence of his studies in Yunnan [though France ruled over Indochina since 1887, which may have allowed for other routes of influence, such as Vietnamese traditional doctors living in France]. Soulié de Morant adopted local custom as his own, and it was said that when he dressed up, his speech and manner were indistinguishable from a native Chinese, and so he earned the respect and trust of his teachers, who supplied him with the most precious texts and instruction. He became so proficient a practitioner that in 1908 the Viceroy of Yunnan certified him as a "Master Physician-Acupuncturist" [so, just four years after meeting Dr. Yang and beginning study of acupuncture].

One other Oriental influence on Soulié de Morant came from Japan, where he spent a month in 1906 because of his own poor state of health, and is reflected in Soulié de Morant's later citation of Japanese works in his publications. Thus, from its inception, the European acupuncture which Soulié de Morant inaugurated reflected aspects of Chinese, Japanese, and Vietnamese traditions. In fact, Soulié de Morant also cited several classical Korean texts, so that tradition was represented, too.

Soulié de Morant returned to France in 1918, but it was not until 1927 that his career in acupuncture really began there. At that time, he brought his daughter for medical treatment to Dr. Paul Ferreyrolles (1880-1955), a member of a study group of physicians investigating alternative medicine. This study group prevailed upon Soulié de Morant to abandon all his other interests and translate the classical Chinese medical texts into French and train them in acupuncture treatment. This he did, while also developing his own clinical practice, first under medical supervision in several hospitals, and later in private practice. He also experimented on himself, needling different points to see their effects, and kept careful records which he used in his subsequent publications.

Among Soulié de Morant's sources, aside from his extensive practical training, he used many classical Oriental texts, but the main ones were two Ming Dynasty Chinese tests: Zhenjiu Dacheng (Great Compendium of Acupuncture and Moxibustion; 1601) and Yixue Rumen (Basics of Medical Studies; 1575). He was also influenced by the Japanese work of Sawada as communicated by Nakayama, whose book Soulié de Morant translated into French with the assistance of the Japanese George Ohsawa (Japanese name: Sakurazawa Nyoitchi; 1893-1966, one of the originators of "macrobiotics").

His first writing about acupuncture was an article in the French Homeopathic Journal in 1929, in collaboration with Ferreyrolles, and his first serious book about acupuncture, Précis de la vrai acuponcture chinoice, was published in 1934. All together, he wrote over 20 articles and books on acupuncture, his magnum opus being L'Acuponcture Chinoise, the first part of which appeared from 1939-1941, but was only published in its entirety posthumously in 1957, and later in English translation (title: Chinese Acupuncture) by Paradigm Press (1994).

The students of Soulié de Morant, including Jean Niboyet (1913-1968, founder of the Mediteranian Acupuncture Association), Albert Chamfrault (ca. 1912-1971; French Association of Acupuncture), and Roger de la Fuÿe (?-1961), pushed forward the field of acupuncture with translations, associations, conferences, and developing clinical practices.

During the 19th century, many of the European writings about acupuncture focused on its use for rheumatism, gout, and other pain disorders. This emphasis continues to this day; the dominant use of acupuncture in the West, especially amongst medical acupuncturists, is for the "musculoskeletal" problems. The unique approach taken in France, which has been formalized and promoted in the study groups and workshops of the French Acupuncture Association (AFA), led to description of two groups of points. According to the French medical acupuncturists Gérard Guillaume and Mach Chieu (as described in their book Rheumatology and Chinese Medicine), one type of points have either global effects or affect an entire channel (or axis, see below); these include most of the transport points, cleft points, source points, and connecting points. The others are specific for the area to be treated, and include mainly associated points, alarm points, and barrier points. Guillaume and Cheiu point out that "barrier points are extremely important in the treatment of pain." Dan Bensky has written about the French system (www.siom.com) and a portion of his presentation has been adopted for presentation here. Among the key concepts of the French system are use of the eight diagnostic parameters, grouping of acupuncture channels into axes, and the above-mentioned focus on barrier points.

The eight diagnostic categories (deficiency/excess, cold/hot, interior/exterior, yin/yang) are applied, in the French system, to the diagnosis of local musculoskeletal pain, particularly joint pain, rather than just to the general syndromes as is commonly done in the TCM system. For example, pain that is lessened with pressure or support is classified as deficient while that which gets worse is considered to be of an excess nature. Pain that is lessened by heat and increased by cold is considered to be of a cold nature, and conversely for the heat type. The pain may come from invasion of external pathogenic factors and be lodged in the painful joint or muscle, or may come from interior disharmonies (of the internal organs) and migrate from there to the affected part. A yin-type pain is dull, throbbing, of moderate intensity, chronic, occurring or aggravated at night, and deep. A yang-type pain is sharp, violent, paroxysmal, stabbing, burning, intense, acute, diurnal, and superficial.

The French place a strong emphasis on the channels, more so than on point sets as often done in modern TCM in China. The twelve channels are viewed as six pairs of channels: two greater yin channels, two lesser yang channels, etc. (taken from the six-fold system depicted in the Neijing Suwen for acupuncture and repeated in the Shanghan Lun for herbs). The functions of the two channels within each pair are understood to be related and so are the manifestations of their disharmonies. Each of these pairs is known as an axis (or great channel).

The concept of barrier points originally came from the Chinese word guän, often translated as barrier or gate. Several French doctors were struck by the number of points that have this word in their name (either primary name or alternate) and they also noted the importance of the concept of barriers or gates in the discussion of joint problems in chapter 60 of the Neijing Suwen. Using this as a point of departure, they described each joint as a place through which physiologic energies (qi and blood in TCM terms) pass, as through an open gate; under certain pathological circumstances, the joint space can turn into a barrier (closed gate) that obstructs the circulation. The yin and yang qi enter and exit the joints. Utilizing the eight categories and properties of channel flow in the axes, the practitioner is to determine the fundamental nature of the disorder, specifically whether the blockage involves the yin or yang qi as it is either entering or exiting the joint. The barrier points (which are originally picked on the basis of traditional descriptions of their channels, specific point indications, the point names, and other factors) are then to be selected as the main part of treatment. These points are depicted in the following table.

Barrier Points in the French Energetic Acupuncture System

| Yang Exiting | Yang Entering | Yin Exiting | Yin Entering | |

| Shoulder | SI-11 | LI-15 | LU-2 | PC-2 |

| Elbow | TB-13 | TB-7 | HT-6 | HT-6 |

| Wrist | LI-9 | SI-6 | PC-4 | LU-6 |

| Hip | BL-29 | ST-31 | SP-12 | LV-11 |

| Knee | GB-33 | GB-36 | KI-5 | KI-5 |

| Ankle | ST-37 | BL-63 | LV-6 | SP-8 |

EuroTCM is attempting to recruit participation of Chinese medicine organizations across Europe in a central information clearing house, along with work towards unifying education and laws. Following is a table of current member organizations, which represent only a fraction of those currently operating in Europe (listed here are the colleges and professional organizations involved with acupuncture and TCM generally):

| Country | Abbreviation | Full name | Type |

| Austria | MED CHIN | Medizinische Gesellschaft für Chinesische Gesundheitspflege in Österreich | College |

| PROTCM | Austria Austrian Professional TCM Federation | Professional org. | |

| TCMA-W | TCM Academy - Campus Wien | College | |

| TCM-U | TCM University | Private University | |

| Belgium | BAF | Belgian Acupunctors Federation | Professional org. |

| BATCM | Belgian Association of Traditional Chinese Medicine | Scientific org. | |

| OTCG | Opleidingsinsituut Traditionele Chinese Geneeswijzen | College | |

| Bulgaria | BAAPT | Bulgarian Acupuncture Association of Physical Therapists | Professional org. |

| Czech Republic | CSBS | Ceskoslovenska Sinobiologicka Spolecnost | College |

| CSBSPTCM | Praktici TCM | Acupuncture org. | |

| NBJ | Foundation of the white crane | Professional org. | |

| TCMB | TCM Bohemia - Klinika Tradicni Cinske Mediciny | Clinic | |

| England | BC | Bodyharmonics Centre | College |

| Germany | ABZ Süd | Ausbildungszentrum Süd | College |

| DBVTCM | Deutscher Berufsverband für TCM | Professional org. | |

| MFTCM | Mercurius Chen Xing | College | |

| TCMA-B | TCM Akademy Campus Berlin | College | |

| TCMA-M | TCM Akademy Munchen | College | |

| Greece | ESPKI | Elleniko Sillogos Paradosiakis Kinezikis latrikis | Professional org. |

| HAOTCM | Hellenic Academy of TCM | College | |

| Hungary | H.SH.T | Hungarian Shaolin Temple | College |

| Italy | SIA | Societa Italiana di Agopuntura | College |

| Ireland | ACMO | Acupuncture and Chinese Medicine Organisation | Professional org. |

| AFI | Acupuncture Foundation TCM Training Programme | College | |

| AFPA | Acupuncture Foundation Professional Association | Professional org. | |

| AIAc | Association of Irish Acupuncturists | Professional org. | |

| Netherlands | DDF | Dutch Dao Foundation | Professional org. |

| HTUTCM | Hwa To University of Traditional Chinese Medicine | College | |

| OC | Oriental College | College | |

| ZHONG | Ned. Vereniging voor Traditionele Chinese Geneeskunde | Professional org. | |

| Serbia/Montenegro | RHCI | Railway Health Care Institute | Professional org. |

| SJC | Balkan Su Jok College | College | |

| Slovac Republic | SINBIOS | Slovenska Sinobiologicka Spolecnost | College |

| Slovenia | SAATCM | Slovenian Association of Acupuncture and TCM | Professional org. |

| Sweden | CESAMQ | Cesamq international TCM organization | College |

| NJA | Nei Jing College | College | |

| SAA-TCM | Swedisch Acupuncture Association | Professional org. | |

| STCMS | Society of Traditional Chinese Medicine Sweden | Professional org. | |

| YSTCM | Yangtorp School of TCM | College |

In the Journal of Traditional Chinese Medicine (2000; volume 20, number 3, pages 231-240), a group of eight Italian medical acupuncturists reported on their comparison of drug therapy versus acupuncture for migraine. They evaluated 120 patients affected by migraine treated at four public health centers. Acupuncture therapy focused on use of 5 points: touwei (ST-8), xuanlu (GB-5), fengchi (GB-20), lieque (LU-7), and dazhui (GV-14), all but the last mentioned point were treated bilaterally. Patients were evaluated after 6 months and 12 months of therapy. The authors concluded that acupuncture was a cost-effective alternative to modern drug treatments.

Numerous clinical reports are published in Italian, mainly in the SIA Journal. Following is a sample abstract of a report on use of acupuncture for pain:

Title: Acupuncture Therapy for Dysmenorrhea

Authors: Stefania Bresciani, Raffaella Mezzopane, Roberto Malavasi, Alberto Lomuscio

Institutions: Scuola di Medicina Naturale and Divisione di Ginecologia Ospedale San Paolo - Milano

Published in: SIA Journal #108, December 2003 (pp: 36-40)

Summary: Thirty women with primary dysmenorrhea have been treated with acupuncture, following a fixed protocol. The authors have evaluated the intensity and duration of pain, the number of work days lost every month, the amount of drugs used to control the pain of menstruation, and associated symptoms. The results show a very significant reduction of all these parameters. It is suggested to use acupuncture therapy in association with classical Western therapy in all the cases of primary dysmenorrhea.

Following are images of the SIA journal cover and the Lao Dan product packaging to illustrate the work being done in Italy towards developing the field of TCM.

SIA Journal Cover |  Label of Lao Dan Chinese Herb Products from Italy |

September 2004