Jisheng Fang

A Book of Formulas to Promote Well-Being

The Jisheng Fang was written by Yan Yonghe, a little known but highly regarded physician of the Song Dynasty (see Appendix 1). Published in 1253, the text is in 10 volumes, each one made up of several subsections that are comprised of an essay followed by prescriptions. The Jisheng Fang had 79 essays on the subjects of internal medicine, external diseases, gynecology, pediatrics, and miscellaneous diseases, with 450 formulas (1, 2). In addition to providing new formulas, also includes formulas from other Song Dynasty works, such as Taiping Huimin Hejiju Fang and Sanyin Fang, and simple folk remedies. In the Ming edition that is still reprinted today, some of the original content has been lost: it consists of only 8 volumes that contain 56 of the essays and a total of 240 formulas. One of Yan's followers, Chong Dingyan, wrote a sequel to the text; it has been called Yanshi Jisheng Xufang (Master Yan's Continuation of the Jisheng Formulas) or Chong Dingyan Shi Jisheng Fang (Master Chong Dingyan's Jisheng Fang) containing 90 additional remedies. It is often considered a part of the original, together called Jisheng Fang. More than 20 of the formulas from these two works are retained in modern TCM literature (3).

The Jisheng Fang was written during the middle of the Jin-Yuan medical reform period (1127-1368), when several competing ideas about the main causes of disease were presented (see: The Jin-Yuan medical reforms). Yan Yonghe was a younger contemporary of Li Dongyuan, also known as Li Gao (1180-1251), who was the recognized leader of one of four schools of medical thought that developed at this time. Li's school emphasized tonification of the spleen and stomach, because he believed that digestive weakness-caused by poor diet, worrying, and overwork-led to many diseases. The main text of the school was Li's compendium Pi Wei Lun (Treatise on Spleen and Stomach; published 1249). The most famous formula to come from his work is Buzhong Yiqi Tang, the formula for tonifying the center (with ginseng, astragalus, atractylodes, and baked licorice) and regulating the flow of qi (with bupleurum and cimicifuga used to raise the yang qi).

Yan Yonghe, like Li Gao, emphasized the importance of the spleen and stomach-representing the digestive system-in the cause of and treatment of diseases. However, he supported the concept of the "pre-natal school," invoking the fundamental role of the kidney fire. The prenatal school had been the forerunner of Li's spleen/stomach school, which, instead, was based on the "post-natal" spleen/stomach. Xu Shuwei (1079-1155), a physician who represented the prenatal school and was author of Leizheng Puji Benshi Fang (Classified Effective Prescriptions for Universal Relief), stated (4):

When the kidney qi is timid and weak, the genuine original qi is in a degenerated and exhausted condition; then there is inability to digest meals. As rice and grains in a cooking vessel which has no fire beneath it will not be ready to eat, when the genuine fire of the kidney is not sufficient, the food is not cooked-the stomach is unable to transform and digest it.

The pre-natal school compared the stomach to a cooking vessel heated by a fire. Just as food is cooked in a wok to make it more tasty and digestible, when properly heated, the stomach is able to convert the food into usable qi. The spleen then transports the foods' basic flavors-its essential qi-to nourish the organs. The properly warmed stomach will break down the food materials so that the spleen can further transform and transport them, such as when it nourishes the lungs by raising the transformed food essence to them.

The fire that warms the stomach is the mingmen fire (Life Gate; Kidney Qi; Genuine Fire). If this fire weakens, then the food is not properly digested, and one can suffer from food stagnation with transformation of the residual mass to pathologic dampness and phlegm. According to this school of thought, the mingmen fire is a key focus of attention for the physician, being even more important than the stomach and spleen organs that it supports. The "prenatal" school gets its name from the concept that the original kidney essence, determined while in the womb, gives rise to this mingmen fire, while the postnatal school gets its name from the idea that the spleen and stomach develop with maturation of the infant who, at first, is unable to consume food (5).

The designation of prenatal and postnatal schools was explained later by Li Zhongzi (1588-1655), referring to the early days (prenatal) and later days (postnatal) (6):

Why are the kidneys the roots of the early days? Even before the fetus assumes any form, the two kidneys are already in existence. They therefore constitute the roots of the zangfu, of the 12 blood channels, the roots of inhalation and exhalation, and the source of the triple burner. The very beginning of human existence depends on the kidneys. Therefore, it is said that the source of early days lies in the kidneys. Why is the spleen called the source of late days. When the infant assumes its bodily form and does not eat for a day, it becomes hungry. When it has received no nourishment for seven days, the intestines and stomach dry up and the baby dies. In the classic it is written: 'Whenever sufficient nourishment is present, life flourishes; where the supply of food is interrupted, life is doomed.' If the influences of the stomach have finally been destroyed, all medicines are of absolutely no use. As soon as the body assumes its physical form, it requires the influences contained in foods....For the entire course of his life, man depends on these influences, thus we speak of the roots of late days.

In short, life cannot begin and the body cannot be formed without the essence stored in the kidneys, hence these are the root of the beginning of life. However, life cannot be sustained without the effective function of the stomach and spleen to take in and absorb nutrients, hence the continuation of life is rooted in these organs. The reason this distinction is deemed an important consideration in traditional Chinese medicine is that one of the primary issues debated over the centuries was: at which pivotal point should medical intervention be aimed? Is it warming the mingmen? Tonifying the spleen and stomach? Regulating the heart? Getting rid of pathological fire? Nourishing the yin? Of course, one can conclude-consistent with the doctrine of modern TCM-that for each individual one must analyze the constitution, disease influences, symptoms, and signs, and treat the individual accordingly. Yet, there had long been a hope entertained that one could identify a single primary basis for most disease. It is for this reason that there were the competing schools of the Jin-Yuan medical reform, each vying for the position of having identified the key to disease causation and, therefore, the associated prevention and treatment strategies that would work best.

Yan Yonghe considered that indigestion, stuffiness of the chest and abdomen, and loose stools are examples of problems due to "degeneration and deficiency of the genuine fire (mingmen)," with the resulting inability of the spleen and stomach to steam and cook the food, followed by symptoms of phlegm-fluid accumulation. Xu Shuwei, his predecessor in this school of thought, had advocated that when tonifying the spleen "the constant warming and tonifying of kidney qi is essential." But Yan went a step further and indicated that "tonifying the kidney qi is better than tonifying the spleen."

The importance of mingmen fire persisted as a significant medical view for several centuries. For example, during the late Ming Dynasty, a "warm nourishment" school developed that was based on this concept. The therapeutic approach involved the use of warming tonics to invigorate the kidney qi and the spleen yang. Li Zhongzi, who was quoted above in relation to the distinction of pre- and post-natal schools, was a prominent member of the warm nourishment school, along with Xue Ji (1486-1558), Sun Yikui (1522-1619), Zhang Jingyue (1563-1640), and Zhao Xianke (1573-1644). Zhao specialized in the theory of the mingmen, and elaborated the functions of mingmen in relation to each of the viscera. In relation to the spleen and stomach, he said: "without it [mingmen fire], they are unable to steam and ferment the fluid and grains, and the production of the five tastes will be impaired."

There had been an ongoing debate about the meaning of mingmen. In the Neijing ,the mingmen was directly associated with the eyes, but in the Nanjing (Difficult Questions, a series of inquiries into issues raised in the Neijing), the mingmen was associated with the kidneys. It was said, based on the Nanjing statements, that the left and right kidneys were different: the left is associated with kidney yin and the right with kidney yang and with the mingmen. Later, several authorities contested the idea that the two kidney lobes differed from one another, and, instead, placed the mingmen in the center of the kidneys and as the key element of the lower burner of the triple burner system (sanjiao). The mingmen contained, within this intermediate location, both a mingmen fire (yang aspect) and a mingmen water (yin aspect). From the discussion in the Nanjing and afterward, the mingmen was recognized as a key to life: without its warming influence, nothing in the body would function, nothing would move. Zhang Jingyue elaborated:

The mingmen controls both kidneys and both kidneys belong to the mingmen. Mingmen is the mansion of both water and fire, the house of yin and yang, the sea of essence and blood, the nest of life and death. If the mingmen is depleted and damaged, the five zang and six fu lose their sustenance, and the yin and yang will become sick, causing all types of disorders.

One of the main formulas for treating kidney qi deficiency had been presented in the ancient Jingui Yaolue (220 A.D.), which had become quite popular during the Song Dynasty and influenced the medical reforms that were soon to come. The formula, Bawei Dihuang Wan (Rehmannia Eight Formula), later became known as Jingui Shenqi Wan (the Kidney Qi Pill from the Jingui). This formula, as understood in modern times, relies on cinnamon and aconite to invigorate the mingmen fire (or kidney yang) and rehmannia to nourish the mingmen water (or kidney yin). The role of rehmannia is dual and based on the fundamental yin/yang concept: on the one hand, it supplements the yin essence that nourishes the yang; on the other hand, it helps the yin essence control the yang and prevent it from flaring up. Zhang Jingyue always emphasized the first point-that the "deficiency of mingmen fire is due to depletion of genuine yin [mingmen water]-hence he frequently included rehmannia in formulas that he designed to treat the weakness of yang.

Yan Yonghe demonstrated a particular interest in the problem of phlegm-fluid accumulation and adverse flow of qi that results from spleen and stomach disorders. Several of his formulas relied on spleen tonification with ginseng, which also supplements the yang qi. For dampness elimination, he relied upon citrus (zhupi), atractylodes (baizhu), hoelen (fuling), and, for severe cases with obvious edema, areca peel. For rectifying stomach qi he used fresh ginger and pinellia. To invigorate the kidney qi, aconite, cistanche, cuscuta, deer antler, cinnamon, and lindera were used. These herbs were recommended as therapies for enhancing mingmen fire by another contemporary of Yan, Wang Haogu (1210-1300) in his book Materia Medica of Decoction (Tangye Bencao).

Over time, Yan Yonghe was nearly forgotten, and he has no biography listed in the major medical texts. But, his book became famous, particularly for its formulas that tonify the stomach and spleen, rectify qi circulation, dispel dampness, and transform phlegm. His best-known formula is Gui Pi Tang (Decoction for Returning the Spleen), which is understood as a prescription to warm up the spleen and stomach by nourishing the heart (within the Five Elements pattern, there is the concept that the fire element associated with the heart engenders the earth element associated with the spleen).

The original formulas was:

| Gui Pi Tang | |

| astragalus | 30 g |

| ginseng | 15 g |

| atractylodes | 30 g |

| hoelen | 30 g |

| licorice (baked) | 10 g |

| zizyphus | 30 g |

| saussurea | 15 g |

The ingredients would be ground to powder, and then made into a tea by brief boiling along with fresh ginger and jujube. This formula has the same qi-supplementing basis as Buzhong Yiqi Tang, namely, the combination of ginseng, astragalus, atractylodes, and baked licorice. Astragalus and ginseng are thought to invigorate the heart qi, while zizyphus nourishes the heart blood (by analogy, these three herbs correspond to cinnamon, aconite, and rehmannia, respectively, in the Rehmannia Eight Formula). Gui Pi Tang was adjusted 300 years later (described in the book Jiaozhu Furen Liangfang) to include tang-kuei and polygala, which is the formulation that comes down to us today.

Other formulas described by Yan include several that are well-known, including Qipi Yin (Seven Peels Drink) for getting rid of damp and treating edema, Jiawei Shenqi Wan (modified Rehmannia Eight Formula) for treating dampness and numbness in the legs, and Ditan Tang (Phlegm-scouring Decoction) for resolving phlegm obstruction of the orifices (see the Appendix 2 for a listing of major formulas of the Jisheng Fang).

The translation of the title Jisheng Fang varies. Some translate it as Formulas to Aid the Living; others designate it Formulas to Save Lives. Fang simply means formulas or prescriptions; sheng refers to life, particularly in the sense of generation and growth, but the character is usually not used alone; rather it is combined with another character to produce a more specific meaning, though the second character can then be dropped in producing phrases like the book title. Ji means to help or aid or to provide relief. The title of Yan's book may be better translated as Formulas to Promote Well-Being, as sheng can be taken as short for shenghuo, referring to life and well-being, while ji can mean to alleviate suffering and bring relief. The title of another famous medical text, Puji Fang, is generally translated as Formulas for Universal Relief; which is also the translation for Puji in Xu Shuwei's book mentioned previously; so ji is used in this context to mean "bring relief." Only some of the formulas in Yan's extensive work might be characterized as life-saving, so the translation Formulas to Save Lives seems less suited. Most of the formulas are health-promoting in nature, and since one naturally uses formulas to aid the living, the other translations (commonly made and perhaps technically correct from the Chinese viewpoint) are probably not as valuable for our understanding of the text. So, Formulas to Promote Well-Being may be the translation closest to the original intent in naming the book Jisheng Fang.

December 2002

The Jin-Yuan medical reforms owed much of their impetus to physicians working in Hubei Province. Li Gao (1180-1251), head of the spleen/stomach school, was from that province and was influential in Yan's work. The dates of Yan's birth and death are not known but have been determined to be approximately 1206-1268, so he was able to learn from the elder Li Gao while Li was still vigorously working.

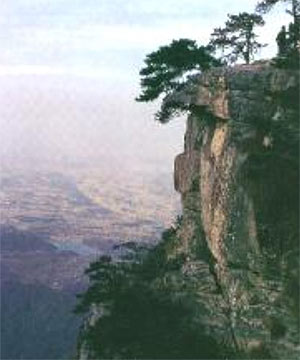

Yan was born and lived near Lushan (Mount Lu). This famous mountain is situated at the outskirts of Jiujiang city at the northern tip of Jiangxi Province adjacent to Hubei (see map below). It's rugged beauty has influenced poets (it is said that over 1,500 of them climbed this mountain for inspiration), scholars, wise men, and religious seekers. On the mountain is the Donglin Monastery built in 384 A.D.; it is the birthplace of the Lian Sect (Pure Land) of Buddhism. Solitary and imposing, Lushan towers over the southern bank of the Yangtze River, leaving behind its shadows upon the huge Boyang Lake.

As a result of tremendous rubbing and grinding of glaciers, its sharp peaks and cragged cliffs look all the more precipitous. The enveloping clouds and mists make it very hard to define the true shapes of the peaks and ridges. The rapid streams cascade down and form numerous deep pools and hanging waterfalls. To describe the infinite variety of fantastic shapes of Lushan Mountain, Sudongpo (a famous Song Dynasty poet, 1037-1101) wrote in his poetic masterpiece: "I can't tell the true shape of Lushan, because I myself am in the mountain!"

Anhui Province, to the northeast of Lushan, is one of China's largest producers of medicinal herbs. Most of the herbs in Yan's formulas come from that province today. The region surrounding Jiujiang was famous for its production of magnolia bark, one of the important ingredients Yan used for the treatment of stagnated fluids. Unfortunately, most of the trees were felled in recent years.

For ease of understanding Yan's approach to therapy, his formulas that come down to us today are here divided into three groups; tonic and warming formulas, surface relieving formulas, and formulas for accumulation, heat, and disordered stomach qi. The details of the formula ingredients and proportions are relayed from Thousand Formulas and Thousand Herbs of Traditional Chinese Medicine (3).

| Renshen Hutao Tang (Ginseng and Walnut Combination) | |

| Ginseng | 6-9 grams |

| Fresh ginger | 5 pieces |

| Walnut | 5 nuts |

This simple prescription warms the spleen, lungs, and kidneys to treat cough, asthma, and fullness in the chest.

Jiawei Shenqi Wan or Jisheng Shenqi Wan

(Rehmannia Eight Formula with achyranthes or cyathula and plantago seed added,

sometimes called Achyranthes, Plantago, and Rehmannia Formula)

| Rehmannia | 15 g |

| Cornus | 30 g |

| Dioscorea | 30 g |

| Alisma | 30 g |

| Hoelen | 30 g |

| Moutan | 30 g |

| Cinnamon bark | 15 g |

| Aconite | 15 g |

| Cyathula | 15 g |

| Plantago seed | 30 g |

The ingredients are to be ground to powder, made into pills, and taken with rice water. It warms the yang, tonifies the kidneys, assists the qi in transforming water, and promotes urination to reduce edema.

| Jisheng Tusizi Wan (Dodder Seed Pill) (Equal parts all ingredients): |

| Cuscuta Cistanche Aconite Antler Alpinia Lindera Dioscorea Oyster shell Schizandra Gallus Mantis |

The herbs are to be powdered and made into pills. The formula warms the kidney, invigorates yang, dispels abdominal chills, and astringes essence.

| Simo Tang (Four Milled Herbs Decoction) | |

| Ginseng | 3 g |

| Areca seed | 9 g |

| Aquilaria | 3 g |

| Lindera | 9 g |

The herbs are to be ground to powder and the briefly decocted. The formula regulates flow of qi, warms the kidney and spleen, alleviates fullness of chest and abdomen. It is used for constraint of liver qi due to injury from emotional upset, with uprising of stomach qi that adversely affects the appetite.

| Shi Ti Tang (Kaki Combination) | |

| Kaki | 9 g |

| Clove | 6 g |

| Fresh ginger | 6 g |

The herbs are decocted; the formula warms the middle burner and helps overcome upward flow of stomach qi. This prescription is used for hiccoughs due to cold stomach.

| Xiong Su San (Cnidium and Perilla Formula) | |

| Cnidium | 10 g |

| Atractylodes | 10 g |

| Citrus | 10 g |

| Pueraria | 10 g |

| Perilla | 5 g |

| Ophiopogon | 10 g |

| Peony | 10 g |

| Licorice | 10 g |

The ingredients are to be decocted with fresh ginger and green onion. The formula resolves the surface, dispels wind-cold, and reinforces the spleen.

| Ju Su San (Citrus and Perilla Formula) | |

| Citrus | 3 g |

| Apricot seed | 3 g |

| Perilla | 3 g |

| Atractylodes | 3 g |

| Pinellia | 3 g |

| Schizandra | 3 g |

| Licorice | 1.5 g |

| Fritillaria | 3 g |

| Morus bark | 3 g |

The ingredients are to be ground to powder, then briefly decocted with fresh ginger. The formula is used to ventilate the lungs, resolve phlegm, alleviate cough, and resolve surface symptoms. It is deemed useful for common cold with cough.

| Canger San or Cangerzi San (Xanthium Formula) | |

| Angelica | 30 g |

| Magnolia flower | 15 g |

| Xanthium | 7.5 g |

| Mentha | 1.5 g |

The herbs are ground to powder and taken in doses of 6 grams each time with green tea. It is used mainly for sinus congestion with sticky but profuse discharge accompanied by headache.

| Ditan Tang (Pinellia and Arisaema Combination; Phlegm-Scouring Decoction) | |

| Pinellia | 8 g |

| Arisaema-bile | 8 g |

| Citrus | 6 g |

| Chih-shih | 6 g |

| Hoelen | 6 g |

| Ginseng | 3 g |

| Acorus | 3 g |

| Licorice | 2 g |

| Bamboo | 2 g |

The herbs are to be decocted. The formula is used for spleen/stomach weakness that leads to phlegm accumulation that pours over into the orifices, causing stroke with stiff tongue and difficult speech.

| Daotang Tang (Phlegm-expelling Decoction) | |

| Pinellia | 6 g |

| Arisaema (baked) | 3 g |

| Red citrus (juhong) | 3 g |

| Chih-shih | 3 g |

| Hoelen | 3 g |

| Licorice | 2 g |

This is a modification of Ditan Tang. The ingredients are ground to powder and boiled with ten slices of fresh ginger. This formula is used for oppressive phlegm accumulation, causes fullness of the chest with expectoration of thick, sticky phlegm, or vomiting and loss of appetite due to phlegm stagnation of the stomach; other symptoms include headache, dizziness, vertigo, and stroke due to uprising phlegm blocking the orifices.

| Jupi Zhuru Tang (Citrus and Bamboo Combination) | |

| Red Hoelen | 30 g |

| Citrus | 30 g |

| Loquat | 30 g |

| Ophiopogon | 30 g |

| Bamboo | 30 g |

| Ginseng | 15 g |

| Baked Licorice | 15 g |

The herbs are to be decocted with 5 pieces of fresh ginger. The formula is used to clear uprising stomach qi due to stomach heat, with vomiting and reduced appetite accompanied by thirst. This formula is modified to Jisheng Jupi Zhuru Tang by adding pinellia, with similar indications.

| Chixiaodou Tang (Phaeseolus Combination) Equal amounts of all ingredients (15 grams each) |

| Phaeseolus Tang-kuei Poke Alisma Forsythia Red peony Stephania Polyporus Morus Euphorbia |

These herbs are to be decocted. The formula is used to clear heat, eliminate dampness, and dispel heat from the blood. Applications include treatment of sores and carbuncles, irritability, thirst, and reduced urination.

| Qipi Yin (Seven Peel Formula) Equal parts (15 grams each) |

| Areca peel Citrus Hoelen peel Fresh ginger peel Blue citrus Lycium bark Licorice bark |

The herbs are to be powdered and then decocted briefly, with a dose of 9 grams each time. The formula regulates the qi, reinforces the spleen, and eliminates dampness accumulation. It is mainly used to treat edema.

| Shipi Yin (Spleen Bolstering Drink) Equal amounts of all ingredients (6 grams each, except licorice, 3 grams) |

| Magnolia bark White atractylodes Chaenomeles Saussurea Tsao-ko Areca seed Aconite Hoelen Dry ginger Licorice |

The herbs are to be powdered and then briefly decocted (the formula is also called Shipi San, referring to the powder). This formula is used for treating edema due to yang deficiency, with edema of the lower body, cold limbs, and not thirst; there is accompanying central stagnation of fluids, with distention of the chest and abdomen, loose stools, and thick greasy tongue coating.

| Juhe Wan or Jisheng Juhe Wan (Citrus Seed Pills) | |

| Citrus seed | 30 g |

| Sargassum | 30 g |

| Kelp | 30 g |

| Ecklonia | 30 g |

| Melia | 30 g |

| Persica | 30 g |

| Magnolia bark | 15 g |

| Akebia | 15 g |

| Chih-shih | 15 g |

| Corydalis | 15 g |

| Cinnamon bark | 15 g |

| Saussurea | 15 g |

The herbs are to be ground to powder and made into pills with yellow wine and taken 9 grams each time with warm wine or salty water; alternatively, the powder can be briefly decocted. This formula resolves phlegm masses and disperses stagnant qi and blood. It is mainly used for the combination of qi stagnation, cold, and damp accumulation, leading to swelling and pain of the lower abdomen (including inguinal hernia or hydrocele).

| Shuzao Yinzi (Decoction for Diuresis) | |

| Alisma | 12 g |

| Phaseolus | 15 g |

| Poke | 6 g |

| Chiang-huo | 9 g |

| Areca peel | 15 g |

| Zanthoxylum | 9 g |

| Akebia | 9 g |

| Chin-chiu | 9 g |

| Areca seed | 9 g |

| Hoelen | 30 g |

The herbs are to be decocted with 5 pieces of fresh ginger. The formula is used to alleviate edema with thirst and difficult urination.

| Qingpi Yin (Decoction for Clearing the Spleen) Equal amounts of the following (12 grams each) |

| Blue citrus Magnolia bark Atractylodes Tsao-ko Bupleurum Hoelen Scute Pinellia Licorice |

The herbs are to be decocted. This formula removes dampness and phlegm, and clears pathogenic heat of the liver that affects the spleen. It is a modification of Xiao Chaihu Tang (Minor Bupleurum Combination), with herbs added to disperse stagnant qi and dampness.

| Zhisou Baihua Wan (Lily and Trichosanthes Formula) | |

| Morus bark | 100 g |

| Aster | 75 g |

| Lily | 75 g |

| Asparagus | 75 g |

| Dioscorea | 75 g |

| Raw Rehmannia | 75 g |

| Fritillaria | 75 g |

| Ophiopogon | 75 g |

| Scrophularia | 75 g |

| Gelatin | 50 g |

| Anemarrhena | 50 g |

| Moutan | 50 g |

| Trichosanthes root | 50 g |

| Stemona | 50 g |

| Apricot seed | 50 g |

| Platycodon | 50 g |

| Scute | 50 g |

| Hoelen | 50 g |

| Licorice | 25 g |

The herbs are to be powdered and made into pills. The formula is for cough and phlegm accumulation associated with lung heat, with spontaneous sweating due to yin deficiency heat.

| Xiaoji Yinzi (Thistle Drink) | |

| Raw rehmannia | 30 g |

| Breea | 15 g |

| Talc | 15 g |

| Akebia | 9 g |

| Typha | 9 g |

| Lotus node | 9 g |

| Lophatherum | 9 g |

| Tang-kuei | 9 g |

| Gardenia | 9 g |

| Baked licorice | 6 g |

The herbs are to be decocted; the formula is used for urination that is blood tinged due to excess of heat in the blood.