LYCIUM FRUIT

Food and Medicine

by Subhuti Dharmananda, Ph.D., Director, Institute for Traditional Medicine, Portland, Oregon

Lycium fruit is the red berry obtained from two closely related plants, Lycium chinense and Lycium barbarum, naturally occurring in Asia, primarily in northwest China (mainly in Qinghai, Gansu, Ningxia, and Inner Mongolia, but east as far as Hebei and west to Tibet and Xinjiang). The fruits from these species are considered interchangeable, though larger fruits are preferred and are more often found on plants of L. barbarum. Lycium is in the Solanaceae family that yields numerous foods, including some that are yellow to red fruits, such as peppers, tomatoes, and the cape gooseberry (a Peruvian species of Physalis).

Lycium fruit is the red berry obtained from two closely related plants, Lycium chinense and Lycium barbarum, naturally occurring in Asia, primarily in northwest China (mainly in Qinghai, Gansu, Ningxia, and Inner Mongolia, but east as far as Hebei and west to Tibet and Xinjiang). The fruits from these species are considered interchangeable, though larger fruits are preferred and are more often found on plants of L. barbarum. Lycium is in the Solanaceae family that yields numerous foods, including some that are yellow to red fruits, such as peppers, tomatoes, and the cape gooseberry (a Peruvian species of Physalis).

The Chinese name for the lycium plant is gouqi and for the fruits is gouqizi (zi is used to describe small fruits); the common name “wolfberry” comes about because the character gou is related to the one that means dog or wolf. The spiny shrub has also been called matrimony vine, for reasons long lost. Carl Linnaeus provided the genus name Lycium in 1753. He is responsible for the species name barbarum, while botanist Philip Miller described Lycium chinense just 15 years later. Lycium is extensively cultivated, especially in Ningxia Province, a small autonomous region formerly part of Gansu, with several production projects initiated since 1987. China now produces over 5 million kilograms of dried lycium fruit each year, most of it for domestic use. The fruits are dried with or without sulfur to yield the market herb, or the fresh fruits may be squeezed for their juice that is then concentrated to preserve it for future use in making various beverages.

TRADITIONAL AND MODERN USES

Although lycium fruit was described in the Shennong Bencao Jing (ca 100 A.D.), its use in traditional formulas was rather limited until the end of the Ming Dynasty period (1368–1644). At that time, it was frequently combined with tonic herbs such as rehmannia, cornus, cuscuta, and deer antler to nourish the “kidney” (as described in Chinese medicine) for the treatment of a variety of deficiency syndromes. This therapeutic approach, using gently warming and “thick” tonifying herbs for nurturing the internal organs, was especially promoted by Zhang Jingyue, whose work is described in the book Jingyue Quanshu(ca 1640). Lycium fruit is depicted by Chinese doctors as having the properties of nourishing the blood, enriching the yin, tonifying the kidney and liver, and moistening the lungs, but its action of nourishing the yin of the kidney, and thereby enriching the yin of the liver, is the dominant presentation. It is applied in the treatment of such conditions as consumptive disease accompanied by thirst (includes early-onset diabetes and tuberculosis), dizziness, diminished visual acuity, and chronic cough. As a folk remedy, lycium fruit is best known as an aid to vision, a longevity aid, and a remedy for diabetes. With the intensive research work done in recent years, reliance on descriptions of centuries-old use of the herb is less important than for many other Chinese herbs, since much is now known about the chemical constituents and their potential health benefits.

Although lycium fruit was described in the Shennong Bencao Jing (ca 100 A.D.), its use in traditional formulas was rather limited until the end of the Ming Dynasty period (1368–1644). At that time, it was frequently combined with tonic herbs such as rehmannia, cornus, cuscuta, and deer antler to nourish the “kidney” (as described in Chinese medicine) for the treatment of a variety of deficiency syndromes. This therapeutic approach, using gently warming and “thick” tonifying herbs for nurturing the internal organs, was especially promoted by Zhang Jingyue, whose work is described in the book Jingyue Quanshu(ca 1640). Lycium fruit is depicted by Chinese doctors as having the properties of nourishing the blood, enriching the yin, tonifying the kidney and liver, and moistening the lungs, but its action of nourishing the yin of the kidney, and thereby enriching the yin of the liver, is the dominant presentation. It is applied in the treatment of such conditions as consumptive disease accompanied by thirst (includes early-onset diabetes and tuberculosis), dizziness, diminished visual acuity, and chronic cough. As a folk remedy, lycium fruit is best known as an aid to vision, a longevity aid, and a remedy for diabetes. With the intensive research work done in recent years, reliance on descriptions of centuries-old use of the herb is less important than for many other Chinese herbs, since much is now known about the chemical constituents and their potential health benefits.

Constituents and Actions

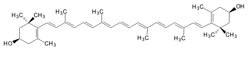

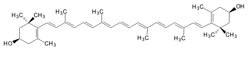

The color components of lycium fruit are a group of carotenoids, which make up only 0.03–0.5% of the dried fruit (1). The predominant carotenoid is zeaxanthin (see structure below), which is present mainly as zeaxanthin dipalmitate (also called physalien or physalin), comprising about one-third to one-half of the total carotenoids. Lycium fruit is considered one of the best food sources of zeaxanthin.

The color components of lycium fruit are a group of carotenoids, which make up only 0.03–0.5% of the dried fruit (1). The predominant carotenoid is zeaxanthin (see structure below), which is present mainly as zeaxanthin dipalmitate (also called physalien or physalin), comprising about one-third to one-half of the total carotenoids. Lycium fruit is considered one of the best food sources of zeaxanthin.

Zeaxanthin is a yellow pigment (an isomer of lutein and a derivative of β-carotene) produced in plants. It contributes to the color of corn, oranges, mangoes, and egg yolks (from dietary carotenoids), and it is also the main pigment of another medicinal fruit recently popularized in China: sea buckthorn (hippophae). When ingested, zeaxanthin accumulates in fatty tissues, but especially in the macula, a region of the retina. It is believed that by having a good supply of this compound, the macula is protected from degeneration, which can be induced by excessive sun exposure (UV light) and by other “oxidative” processes (2–4). Lutein, another yellow carotenoid that accumulates in the macula and provides similar protection, is an ingredient of yellow chrysanthemum flowers (juhua) that are often combined with lycium fruits in traditional Chinese herb formulas to benefit the eyes, including deteriorating vision that occurs with aging and may, in some cases, correspond to macular degeneration. The effective daily dose of these two carotenoids, from food and supplements, has been estimated to be about 10 mg.

Another plant in the Solanaceae family used in Chinese medicine (though rarely), is Physalis alkekengi, the Chinese lantern plant, which contains zeaxanthin dipalmitate as a major active component. In addition, the plant contains some steroidal compounds that have been named physalins, producing some confusion about the use of this term because of its former application to the carotenoid. Physalis is used as a treatment for viral hepatitis, and this effect may be attributed in part to zeaxanthin and also to the steroidal compounds. Physalis is used for treating a variety of inflammatory disorders, perhaps aiding treatment of infections; extracts of physalis have been shown to increase natural killer cell activity when administered to mice.

Another plant in the Solanaceae family used in Chinese medicine (though rarely), is Physalis alkekengi, the Chinese lantern plant, which contains zeaxanthin dipalmitate as a major active component. In addition, the plant contains some steroidal compounds that have been named physalins, producing some confusion about the use of this term because of its former application to the carotenoid. Physalis is used as a treatment for viral hepatitis, and this effect may be attributed in part to zeaxanthin and also to the steroidal compounds. Physalis is used for treating a variety of inflammatory disorders, perhaps aiding treatment of infections; extracts of physalis have been shown to increase natural killer cell activity when administered to mice.

The red carotenoids of lycium have not been fully analyzed. It is believed that part is due to lycopene, the major red pigment in tomatoes and capsicum fruits. The red portion of lycium has been designated as renieratene; the red color overwhelms the yellow of zeaxanthin and the small amount of β-carotene, though the fruits often display an orange tinge due to the yellow components.

Benefits of carotenoid intake are thought to mainly arise from prolonged use. Therefore, lycium fruit, as a source of zeaxanthin and other carotenoids, would be consumed regularly to complement dietary sources, boosting the amount of these components available from fruits and vegetables and egg yolks.

Another component of lycium is polysaccharides, chains of sugar molecules with high molecular weight (several hundred sugar molecules per chain). It is estimated that 5-8% of the dried fruits are these polysaccharides (5), though measures of the active polysaccharides are difficult to undertake, since differentiating functional long chains versus non-functional short chains is challenging; this figure for polysaccharide content is likely on the high side. Studies of the polysaccharides have indicated that there are four groups of them, each group having slightly different structures and molecular weights (6). Although referred to as polysaccharides, the functional immune-regulating substance is actually a polysaccharide-peptide mixture; the amino acid chains maintain a critical structure for the polysaccharide.

Clinical effects of polysaccharides are also somewhat difficult to determine because absorption after oral administration of polysaccharides is limited and may be quite variable; it is estimated that less than 10% of the high molecular weight plant polysaccharides are absorbed, possibly as little as 1%. So, most studies of these polysaccharides are done with isolated cells or with injections of the purified component to laboratory animals, yielding results that may or may not occur when these substances are consumed orally. In one clinical evaluation, cancer patients were treated with a combination of IL-2 and activated lymphokine killer cells plus lycium fruit polysaccharides (which are reported to promote the body’s production of these therapeutic substances), in which patients were given an oral dose of 1.7 mg/kg of the polysaccharides (so, about 100 mg for a 60 kg person), with the reported result that the response rate was higher than without the polysaccharides (7). This dose of polysaccharides is quite low compared to usual clinical practice, and further evaluation is needed.

These lycium fruit polysaccharides, like those obtained from medicinal mushrooms and from several herbs (the best known as a source is astragalus), have several possible benefits, including promoting immune system functions, reducing gastric irritation, and protecting against neurological damage. The latter application has been the subject of several recent studies at the University of Hong Kong, where lycium polysaccharides are proposed, on the basis of laboratory studies with isolated neurons, to be of benefit to those with Alzheimer’s disease, though clinical trials have not yet been carried out (8, 9).

The immunological impacts of polysaccharides have been the primary focus of study (10). One of the primary mechanisms of action for these large molecules may be that they appear to the immune system as though they were cell surface components of microorganisms, promoting activation of a response cascade involving interleukins (such as IL-2) that impact immune cells (such as T-cells). Since the plant polysaccharides are not the same as the structures on particular pathogens, but have a more poorly defined quality, the response is non-specific. It is possible that repeated exposure to large amounts of polysaccharides might result in a lessened response, so that this method of therapy is probably best suited to relatively short duration (e.g., a few weeks). Low dosage exposure may result in no immunological responses, since these polysaccharides are present in several foods in small amounts, and the immune system would be protected from reacting to ordinary exposure levels.

A review of research on lycium fruit appearing in Recent Advances in Chinese Herbal Drugs (11), indicates that polysaccharides from lycium fruit enhance both cell-mediated and humoral immune responses. It was reported, for example, that in laboratory animals, a dose of 5–10 mg/kg lycium fruit polysaccharides daily for one week could increase activity of T-cells, cytotoxic T-cells, and natural killer cells; other studies showed that part of the mechanism of action was via IL-2 stimulation. The end response to polysaccharide administration did not appear to be solely a stimulation of immune activity, however. In a laboratory study of lycium on IgE responses, it was noted that lycium fruit reduced antibodies associated with allergy-type reactions, which was presumed to be accomplished through the mechanisms of promoting CD8 T-cells and regulating cytokines; licorice root had a similar effect (12).

Extraction and isolation of polysaccharides in low concentration is simple, as they are soluble in hot water that is used as an extracting agent. Getting a high concentration of polysaccharides is a more significant task. The easiest method is to first produce a hot water extract of the herb (using more than one extraction to get most of the polysaccharides into solution), and then force the polysaccharides out of solution by adding alcohol, in which they are not soluble; then, the liquid is separated off and the residue is dried to produce the finished polysaccharide product. This method will also condense other large molecules. Although small amounts of highly purified polysaccharides can be produced for laboratory and clinical studies, at this time, commercial extracts containing 40% polysaccharides represent the highest concentration available, while 10–15% polysaccharide content from simple hot water extraction is more common.

A third constituent of interest is the amino-acid like substance betaine, which is related to the nutrient choline (betaine is an oxidized form of choline and is converted back to choline by the liver when it is ingested). When added to chicken feed, betaine enhances growth of the animals and increases egg production; it is currently used in poultry farming because of these effects. In recent years, betaine has been included in some Western nutritional supplement products, especially those used for improving muscle mass, using several hundred milligrams for a daily dose. Betaine was shown to protect the livers of laboratory animals from the impact of toxic chemicals; other pharmacologic studies have shown that it is an anticonvulsant, sedative, and vasodilator. It has been suggested that betaine could aid the treatment of various chronic liver diseases, such as non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. Betaine is found also in capsicum, silybum (the source of the liver-protective flavonoid silymarin), and beets (Beta vulgaris, from which betaine gets its name). The amount of betaine in lycium fruit, is about 1% (10), so to get a significant amount, a large dose of lycium fruit would need to be consumed (e.g., 20–30 grams).

The mild fragrance of the fruits is attributed to a small amount of volatile oils, mainly two sesquiterpenes: cyperone and solavetivone (13). The amount present does not have significant pharmacological functions when lycium is consumed in ordinary amounts. The fruit also contains about 0.15% flavonoids, including rutin and chlorogenic acid (14).

Typical Dosing of Lycium Fruit

Lycium fruit is most often incorporated into complex herb formulas, in which its dose is in the range of 6–18 grams. Since other herbs in the formula could contribute significant amounts of compounds such as carotenoids and polysaccharides, this dose may be insufficient if lycium is used as a single herb remedy instead. There have been a few reports of using lycium fruit as a single herb or as a major component in a small recipe. For example, in the treatment of atrophic gastritis, one of the recommended therapies is to consume lycium fruits, 10 grams each time, twice daily (15). In folk medicine, for diabetes it is recommended to consume 10 grams each time, two or three times daily (16). As a food therapy for strengthening the elderly or debilitated, it is cooked with lean pork, bamboo shoots, and typical Chinese flavorings, and the daily dose would be 15–30 grams (17). As a dietary supplement for eye health (2), a dose of 15 grams per day was deemed beneficial in supplying adequate zeaxanthin (estimated at 3 mg/day). A simple tea for decreased visual perception is made from 20 grams lycium fruit as a daily dose (18). Thus, the dose in complex formulas of 6–18 grams shifts to a dose of 15–30 grams when it is the main herb, or about a 2.5-fold increase in the dose.

A tableted formula for benefiting vision, made from extracts of lycium fruit, cuscuta seed (tusizi), bilberry fruit (a type of blueberry), and marigold flowers (source of lutein), is produced by ITM and called Lycuvin (19). Two tablets of the formula (a typical daily dose) provides lycium extractives from 10 grams of the fruit (with about 3 mg of zeaxanthin); cuscuta extractives from 6 grams of the seeds (a good source of the flavonoid quercetin, and with a polysaccharide content similar to that of lycium fruit); 75 mg of anthocyanins (another visual pigment) from bilberry, and 8 mg of lutein. These quantities are all consistent with high supplementation levels suggested in the literature for eye health, particularly of benefit to the macula.

Like other commonly eaten fruits, lycium is non-toxic. Toxicity studies showed that injection of 2.4 grams/kg of lycium fruit extract did not cause adverse reactions; the LD50 by injection was determined to be about 8.3 grams/kg, a large amount (10). There was one recent report of possible hepatic reaction to consumption of a lycium fruit beverage product (20). A possible case of interaction of lycium fruit with Warfarin (coumadin) was reported (21); however, given the high frequency of use of lycium fruit and of Warfarin, the lack of more reports of interaction suggests that the incidence may be very low.

Himalayan Goji Juice

In the U.S., lycium fruit is already better known as an ingredient of the juice product called Himalayan Goji Juice (goji is another transliteration of gouqi), than as an ingredient in traditional Chinese medicine prescriptions or food therapy. The product was developed by Earl Mindell, who is best known for his book “Vitamin Bible” (which now has a 25th Anniversary revised edition). He learned of lycium fruit from a Chinese herbal specialist in 1995, and introduced a juice product in 2003, which is made from the reconstituted extracts of four fruits: lycium, grape, apple, and pear (with pear puree added). It is provided in bottles of 33 fluid ounces (1 liter), with recommended use of 2–4 ounces per day, so one bottle is about an 8–16 day supply. Very quickly, a number of other companies have imitated this popular product, and some have gone on to make other formulations featuring lycium fruit as a primary or secondary ingredient.

Comparing this juice to the lycium fruit described in traditional Chinese medicine is somewhat difficult. The manufacturer indicates: “One liter of Himalayan Goji Juice contains the polysaccharides equivalent of 2.2 pounds [1 kg] of fresh goji berries.” Typically, a dried berry is about one-sixth the weight of a fresh berry (that is, the moisture content of the fresh fruit is about 83%), so a dose of 2–4 ounces of the juice would correspond to 10–20 grams of the dried fruit, which is in the correct dosage range in accordance with traditional recommendations, though higher doses have been used in some applications. Dried lycium fruit can be eaten whole (sold most in one pound bags, about 23–46 doses of 10–20 grams), and can be obtained at a lower cost because it is in crude form. The makers of this juice, and other similar products, proclaim unique benefits to the juice, mainly because of specific selection of berries, compared to the dried lycium fruits readily available from Chinese herb and grocery stores. The juice is a convenient form of administration and also provides other juices (that yield a more acceptable flavor), so the extra expense may be considered worthwhile, while there is little evidence that would support a contention of differing therapeutic effect if similar amounts of the lycium fruit are obtained from drinking the juice or from eating the dried fruits or taking supplements made from lycium extracts.

An ITM Health Protocol with Lycium Fruit

While ITM has advocated consuming dried lycium fruits, in much the way one would eat raisins or other small dried fruits, as a means of getting an adequate quantity of the fruit, it is recognized that many people prefer other methods of consuming herbs, such as tablets. The following protocol, relying on tableted herbs, provides a good dose of lycium fruit along with other herbs that also have the reputation of nourishing the yin, supplementing the kidney and liver (as described in Chinese medicine terms), benefiting the eyes, enhancing immune functions, and protecting against adverse impact of oxidation:

Tremella 14 (Seven Forests): 5 tablets each time, twice daily

Lycuvin (White Tiger): 1 tablet each time, twice daily

China Rare Fruits Blend (Jintu): 2 tablets each time, twice daily

Tremella 14 is a yin-nourishing combination of crude herbs; about one third of the formula is made of equal parts lycium fruit, tremella (a tree mushroom, yiner), and astragalus (huangqi); these three herbs are excellent sources of active polysaccharides. Lycuvin was described above, and is a source of visual pigments, especially zeaxanthin and lutein, as well as polysaccharides from lycium and cuscuta. China Rare Fruits Blend is a combination of medicinal fruits including lycium and hippophae (shaji) as sources of zeaxanthin; the formula is considered especially useful for nourishing skin, hair, and nails. This protocol of three products provides extract and powder from 15 grams of lycium fruit in a daily suggested dose. The cost of such a protocol is similar to that for consuming the juice products. Although many potential benefits are described for lycium fruit, the goji juice, and these tablets, only the claim of providing useful amounts of carotenoids and other pigments for nourishing the retina (especially the macula) can be adequately verified at this time.

References

- Yong Peng, et.al., Quantification of zeaxanthin dipalmitate and total carotenoids in Lycium fruits, 2006 Plant Foods for Human Nutrition, 60(4): 161–164

- Cheng CY, et.al., Fasting plasma zeaxanthin response to Fructus barbarum in a food-based human supplementation trial, British Journal of Nutrition 2005; 93(1): 123–130

- Trieschmann M, et.al., Changes in macular pigment optical density and serum concentrations of its constituent carotenoids following supplemental lutein and zeaxanthin, Experimental Eye Research 2007; 84(4): 718–728

- Rosenthal JM, et.al., Dose-ranging study of lutein supplementation in persons aged 60 years or older, Investigative Ophthalmology and Visual Science 2006; 47(12): 5227–5233

- Wang Qiang, et.al., Determination of polysaccharide contents in Fructus Lycii, Chinese Traditional and Herbal Drugs 1991; 22(2): 67–68

- Tian M and Wang M, Studies on extraction, isolation, and composition of Lycium barbarum polysaccharides, Journal of Traditional Chinese Herb Drugs, 2006 31(19): 1603–1607

- Cao GW and Yang WG, Observation of the effects of LAK/IL-2 therapy combining with Lycium barbarum polysaccharides, China Journal of Oncology 1994; 16: 428–431

- Chang RC and So KF, Use of Anti-aging Herbal Medicine, Lycium barbarum, Against Aging-associated Diseases, Cellular and Molecular Neurobiology 2007 [in press]

- Yu MS, et.al., Characterization of the effects of anti-aging medicine Fructus lycii on beta-amyloid peptide neurotoxicity, International Journal of Molecular Medicine 2007; 20(2): 261–268

- Zhu Youping, Chinese Materia Medica: Chemistry, Pharmacology, and Applications, 1998 Harwood Academic Publishers, Netherlands

- Zhou Jinhuang, Immunopharmacological activities of yin and yang biomodulatory drugs, in Recent Advances in Chinese Herbal Drugs 1991 Science Press, Beijing

- Yin Jinzhu, et.al., Regulatory action of licorice and lycium fruit on IgE antibodies response, Journal of Beijing Medical University 1992; 24(2): 115–117

- Sannai A, Fujimori T, and Kato K, Isolation of (-)-1,2-dehydro-α-cyperone and solavetivone from Lycium chinense, Phytochemistry 1982; 21: 2986–2987

- Qian JY, Liu D, and Huang AG, The efficiency of flavonoids in polar extracts of Lycium chinense Mill fruits as free radical scavenger, Food Chemistry 2004; 87(2): 283–288

- Wang Qi and Dong Zhilin, Modern Clinic Necessities for Traditional Chinese Medicine, 1990 China Ocean Press, Beijing

- Xu Xiangcai (chief editor), Maintaining Your Health, volume 9 of The English-Chinese Encyclopedia of Practical Traditional Medicine, 1989 Higher Education Press, Beijing

- Zhang Wengao, et.al., Chinese Medicated Diet, 1988 Publishing House of Shanghai College of Traditional Chinese Medicine, Shanghai

- Zong XF and Liscum G, Chinese Medicinal Teas, 1996 Blue Poppy Press, Boulder, CO

- Dharmananda S, A Bag of Pearls, 2004 Institute for Traditional Medicine, Portland, OR

- Haru Amagase, personal communication, July 2007

- Lam AY, Elmer GW, and Mohutsky MA, Possible interaction between warfarin and Lycium barbarum, The Annals of Pharmacotherapy: 2001; 35 (10): 1199-1201

August 2007

Lycium fruit is the red berry obtained from two closely related plants, Lycium chinense and Lycium barbarum, naturally occurring in Asia, primarily in northwest China (mainly in Qinghai, Gansu, Ningxia, and Inner Mongolia, but east as far as Hebei and west to Tibet and Xinjiang). The fruits from these species are considered interchangeable, though larger fruits are preferred and are more often found on plants of L. barbarum. Lycium is in the Solanaceae family that yields numerous foods, including some that are yellow to red fruits, such as peppers, tomatoes, and the cape gooseberry (a Peruvian species of Physalis).

Lycium fruit is the red berry obtained from two closely related plants, Lycium chinense and Lycium barbarum, naturally occurring in Asia, primarily in northwest China (mainly in Qinghai, Gansu, Ningxia, and Inner Mongolia, but east as far as Hebei and west to Tibet and Xinjiang). The fruits from these species are considered interchangeable, though larger fruits are preferred and are more often found on plants of L. barbarum. Lycium is in the Solanaceae family that yields numerous foods, including some that are yellow to red fruits, such as peppers, tomatoes, and the cape gooseberry (a Peruvian species of Physalis).

Although lycium fruit was described in the Shennong Bencao Jing (ca 100 A.D.), its use in traditional formulas was rather limited until the end of the Ming Dynasty period (1368–1644). At that time, it was frequently combined with tonic herbs such as rehmannia, cornus, cuscuta, and deer antler to nourish the “kidney” (as described in Chinese medicine) for the treatment of a variety of deficiency syndromes. This therapeutic approach, using gently warming and “thick” tonifying herbs for nurturing the internal organs, was especially promoted by Zhang Jingyue, whose work is described in the book Jingyue Quanshu

Although lycium fruit was described in the Shennong Bencao Jing (ca 100 A.D.), its use in traditional formulas was rather limited until the end of the Ming Dynasty period (1368–1644). At that time, it was frequently combined with tonic herbs such as rehmannia, cornus, cuscuta, and deer antler to nourish the “kidney” (as described in Chinese medicine) for the treatment of a variety of deficiency syndromes. This therapeutic approach, using gently warming and “thick” tonifying herbs for nurturing the internal organs, was especially promoted by Zhang Jingyue, whose work is described in the book Jingyue Quanshu The color components of lycium fruit are a group of carotenoids, which make up only 0.03–0.5% of the dried fruit (1). The predominant carotenoid is zeaxanthin (see structure below), which is present mainly as zeaxanthin dipalmitate (also called physalien or physalin), comprising about one-third to one-half of the total carotenoids. Lycium fruit is considered one of the best food sources of zeaxanthin.

The color components of lycium fruit are a group of carotenoids, which make up only 0.03–0.5% of the dried fruit (1). The predominant carotenoid is zeaxanthin (see structure below), which is present mainly as zeaxanthin dipalmitate (also called physalien or physalin), comprising about one-third to one-half of the total carotenoids. Lycium fruit is considered one of the best food sources of zeaxanthin.  Another plant in the Solanaceae family used in Chinese medicine (though rarely), is Physalis alkekengi, the Chinese lantern plant, which contains zeaxanthin dipalmitate as a major active component. In addition, the plant contains some steroidal compounds that have been named physalins, producing some confusion about the use of this term because of its former application to the carotenoid. Physalis is used as a treatment for viral hepatitis, and this effect may be attributed in part to zeaxanthin and also to the steroidal compounds. Physalis is used for treating a variety of inflammatory disorders, perhaps aiding treatment of infections; extracts of physalis have been shown to increase natural killer cell activity when administered to mice.

Another plant in the Solanaceae family used in Chinese medicine (though rarely), is Physalis alkekengi, the Chinese lantern plant, which contains zeaxanthin dipalmitate as a major active component. In addition, the plant contains some steroidal compounds that have been named physalins, producing some confusion about the use of this term because of its former application to the carotenoid. Physalis is used as a treatment for viral hepatitis, and this effect may be attributed in part to zeaxanthin and also to the steroidal compounds. Physalis is used for treating a variety of inflammatory disorders, perhaps aiding treatment of infections; extracts of physalis have been shown to increase natural killer cell activity when administered to mice.