return to itm online

SAFETY ISSUES AFFECTING CHINESE HERBS:

Magnolia Alkaloids

by Subhuti Dharmananda, Ph.D., Director, Institute for Traditional Medicine, Portland, Oregon

BACKGROUND

Beginning in 2002, several product liability insurance companies providing coverage for herb product manufacturers began excluding magnolia from their policies. This means that a company that produces a product containing magnolia would not get any of the policy benefits if it were subjected to a lawsuit claiming harm from those products. This action deters most product designers and manufacturers from including this commonly used Chinese herb. Insurers do not provide explanations for their exclusions, which are usually based on the perception that an undue risk of complaints against their policyholders exists. Clearly, if magnolia has the potential to cause severe adverse reactions that would worry the insurers, those who produce such formulas and those who prescribe them ought to know about it.

After an extensive search of the literature, I have found only two potential sources for the insurers' concerns about magnolia, and both appear to involve errors in interpretation. The first source is a 1993 article that appeared in Lancet (1), describing a tragedy at a weight loss clinic in Belgium. In the article, two herbs, Stephania tetrandra and Magnolia officinalis, were suggested to be the cause of renal failure. Soon afterward, both of these botanicals were dropped from the consideration of researchers who followed-up on this case, and attention was turned instead to a species of Aristolochia that had been used at the weight loss clinic as an unintentional substitution for Stephania tetrandra (2). Because it is difficult to distinguish Aristolochia and Stephania roots (the part used) that are in the herb markets, most herb companies now avoid Stephania in order to assure that no Aristolochia enters into their products inadvertently. The alternative is to test each batch for chemical markers that clearly distinguish the two; the testing became reliable only recently. Insurers undoubtedly have been influenced by mention of magnolia in this early report. Numerous expensive lawsuits resulted from the problems with Aristolochia, the basis of these being the Belgian experience reported in 1993. In Belgium, the government bans the use of Magnolia officinalis in herb products, but permits other species of Magnolia, reflecting concern over this one report.

The second source is a Health Canada alert issued about magnolia bark, stating that it "contains tubocurarine and related substances which are known to cause respiratory paralysis in animals and may be toxic to infants and small children." In an extensive search for magnolia bark ingredients, tubocurarine has failed to appear outside of that alert. Thus, if it is present, it must be in a miniscule amount, but the Health Canada statement may have been a simple error, with the intention to say that magnolia bark contains "tubocurarine-like substances." Tubocurarine is a bis-benzylisoquinoline alkaloid (bis means there are two of the basic molecules linked together); magnolia bark contains benzylisoquinoline alkaloids, mainly magnocurarine, so a similarity to tubocurarine exists. Tubocurarine is a drug developed for certain limited uses: it is a muscle relaxant that produces a flaccid paralysis sometimes needed during medical procedures (e.g., some surgeries, endotracheal intubation, and electroconvulsive therapy). All, or most, of the benzylisoquinoline alkaloids have muscle-relaxing effects, though tubocurarine is the most potent one used.

Health Canada's concern about magnolia and its content of these alkaloids was part of the basis for halting import of a U.S.-made herb product labeled for use in children. The product, a tincture called Chest Relief, was cited as containing three potentially harmful herbs: magnolia bark, trichosanthes, and fritillaria. Although the Health Canada action was not broadly publicized, it probably came to the attention of insurers. Health Canada had put magnolia bark on its alert list in 1998, but had taken no action until providing its notification about Chest Relief (because it was labeled for pediatric use) in 2001. However, this alert may be an over-reaction; as described below, the amount of alkaloids of potential concern in magnolia and its products is quite small.

MAGNOLIA IN CHINESE HERBALISM

| Magnolias are a source of Chinese herbal materials that are widely used internationally. There are two basic materials of frequent application: the bark of magnolia, called houpu, and the flower bud of a another magnolia, called xinyi or xinyihua. The flower bud is used almost exclusively for treatment of sinus congestion and sinus headaches, and is taken orally or applied topically (for example, by inhaling the essential oils or placing some of the herb powder or extract in the nose). Magnolia bark, on the other hand, has a very wide range of applications. Many of the formulations with magnolia bark are aimed at treatment of lung disorders (including cough and asthma) or intestinal disorders (infections and spasms); magnolia bark is also a common ingredient in the treatment of abdominal swelling of various causes and edema.

|

Several species of Magnolia are used as source materials, though Magnolia officinalis is the primary source reported for the bark and Magnolia lactiflora is the primary source reported for the flower. The active components of the magnolia materials have been identified (see Table 1 and Figure 1). The flower buds mainly contain monoterpene and sesquiterpene aromatics that are understood to provide the decongestant effect for which they are utilized. Alkaloids have not been detected in the flower buds as yet. The unmistakable pleasant fragrance of magnolia bark is primarily due to the presence of two groups of non-alkaloid compounds: biphenols (magnolol and honokiol are dominant) which have a mild fragrance, and an essential oil with eudesmol as the main component (about 95% of this oil) that has a stronger fragrance.

In samples of magnolia bark from different areas of China, the content of magnolol and honokiol were in the range of 2-11% and 0.3-4.6% respectively (3, 4). Eudesmol (a triterpene) usually comprises just under 1% of the bark. The biphenols and eudesmol are understood to be the main active constituents that confer the desired pharmacological effects. These ingredients are reported to have anxiolytic effects (5), to enhance steroid production by the adrenal cortex (6), inhibit bacteria (4) and pathogenic fungi (7), have antioxidant actions (8), reduce inflammation and pain (9); they may protect against seizures (10) and act as an antidote for intoxication by organophosphorus pesticides (11). The anxiolytic effect of magnolia has been relied upon in production of a commercial product called Sublimiss, made from magnolia bark extract, and described as a substitute for kava (an anxiolytic) and St. John's Wort (an antidepressant).

Magnolia bark also contains a small amount of alkaloids, mainly benzylisoquinoline alkaloids-magnoflorine, magnocurarine, and salicifoline, with traces of oxoushinsunine, anonaine, michelabine-but these alkaloids are not considered important to the clinical actions. They make up only about 1% of the bark, with magnocurarine, the most potent of the alkaloids, at less than 0.1% in most commercial samples (12). The alkaloids may confer some of the antispasmodic effect of magnolia bark when used in high dose decoctions to alleviate bronchiole spasms and intestinal spasms. Magnocurarine was investigated as a potential muscle relaxant drug in Japan (13). A recent evaluation indicates that magnocurarine comprises about 0.2% or less of the commercial magnolia bark (14; see Table 2 and Figure 2).

A substitute sometimes used in China for magnolia bark (houpu) is tuhoupu, from species of Manglieta. These are plants closely related to magnolia; the bark of some Manglieta species grown in certain areas has considerably more of the magnocurarine than the magnolia bark routinely traded (14, 15). There are also some species of Magnolia with high magnocurarine levels (14, see Table 3), but not Magnolia officinalis.

TABLE 1. Constituents of Magnolia officinalis

| Component Found

| Part Where Found

(Quantity When Measured)

|

| α-Eudesmol

| essential oil

|

| α-Pinene

| plant

|

| Anonaine

| plant

|

| β-Eudesmol

| essential oil

|

| β-Pinene

| plant

|

| Bornyl-acetate

| essential oil

|

| Bornyl-magnoliol

| plant

|

| Caffeic acid

| plant

|

| Calcium

| bark (6,350 ppm)

|

| Camphene

| essential oil

|

| Caryophyllene epoxide

| essential oil

|

| Copper

| bark (8 ppm)

|

| Cryptomeridiol

| essential oil

|

| Cyanidin

| plant

|

| Essential oil

| bark (3,000-10,000 ppm)

|

| Eudesmols

| bark (2,820-2,940 ppm)

|

| Honokiol

| plant

|

| Iron

| bark (120 ppm)

|

| Kaempferol

| plant

|

| Liriodenine

| plant

|

| Magnesium

| bark (690 ppm)

|

| Magnocurarine

| plant

|

| Magnoflorine

| plant

|

| Magnolol

| bark

|

| Manganese

| bark (120 ppm)

|

| Michelarbine

| Plant

|

| Potassium

| bark (2,560 ppm)

|

| Quercetin

| Plant

|

| Salicifoline

| Plant

|

| Sodium

| bark (27 ppm)

|

| Zinc

| bark (9 ppm)

|

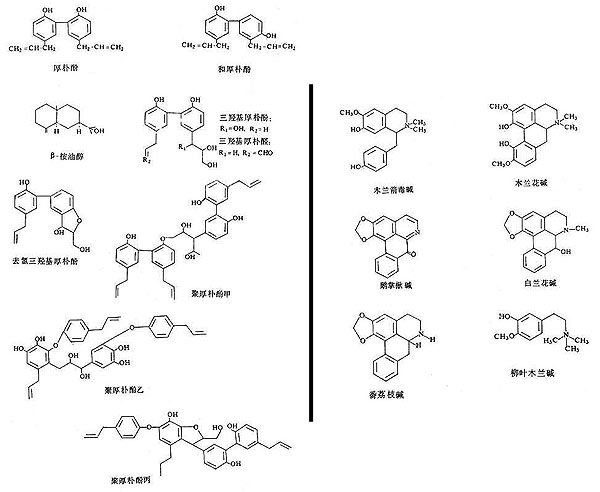

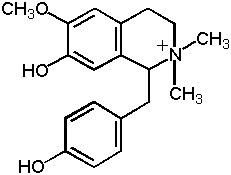

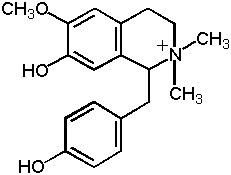

Figure 1: Structure diagrams of magnolia bark active constituents.

Phenolic compounds are shown at the left, quinoline alkaloids are shown at the right.

TABLE 2. Contents of Magnocurarine in Medicinal Magnolia Bark (Houpo)

| Species

| Collection Sites

(Region, Province)

| Magnocurarine Percent of Bark

|

| Magnolia officinalis

| Zhenping, Shaanxi

| 0.150

|

| Magnolia officinalis

| Hanzhong, Shaanxi

| 0.103

|

| Magnolia officinalis

| Ansi, Hubei

| 0.127

|

| Magnolia officinalis

| Nanjiang, Sichuan

| 0.060

|

| Magnolia officinalis var. biloba

| Jinggangshan, Jiangxi

| 0.060

|

| Magnolia officinalis var. biloba

| Guilin, Guangxi

| 0.025

|

| Magnolia officinalis var. biloba

| Lishui, Zhejiang

| 0.201

|

TABLE 3. Contents Of Magnocurarine In Substitute Species

| Species

| Collection Sites

(Region, Province)

| Magnocurarine Percent of Bark

|

| Magnolia wilsonii

| Yaan, Sichuan

| 1.620

|

| Magnolia rostrata

| Tenchong, Yunnan

| 0.061

|

| Magnolia rostrata

| (undesignated region), Yunnan

| 0.316

|

| Magnolia sargentiana

| Ganluo, Sichuan

| 1.465

|

| Magnolia sargentiana

| Muchuan, Sichuan

| 0.031

|

| Magnolia sprengeri

| Nanjiang, Sichuan

| 0.096

|

| Magnolia sprengeri

| Nanchuan, Sichuan

| 0.016

|

| Magnolia sprengeri

| Liuba, Shaanxi

| 0.029

|

| Magnolia sprengeri

| Kangxian, Gansu

| 0.087

|

| Magnolia liliflora

| Nanjing, Jiangsu

| 0.017

|

| Magnolia biondi

| Yangxian, Shaanxi

| 0.038

|

| Manglietia chingii

| Beiliu, Guangxi

| 0.817

|

| Manglietia chingii

| Rongxian, Guangxi

| 0.866

|

| Manglietia szechuanica

| Yaan, Sichuan

| 0.420

|

| Manglietia szechuanica

| Muchuan, Sichuan

| 1.410

|

| Manglietia insignis

| Ximeng, Yunnan

| 0.866

|

| Manglietia insignis

| (undesignated region), Yunnan

| 0.420

|

| Magnlietia yuyuanensis

| Qujiang, Guangdong

| 1.602

|

| Manglietia duclourii

| Zunyi, Guizhou

| Trace

|

| Manglietia glauca

| Wuming, Guangxi

| 0.342

|

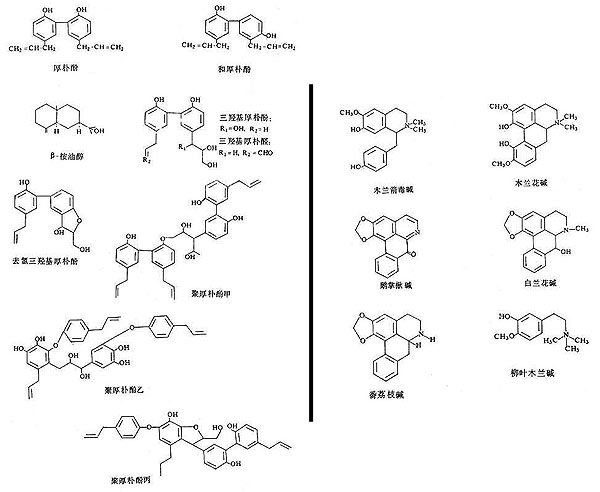

Figure 2: Magnocurarine

QUANTITIES OF THE ALKALOIDS INGESTED

Magnolia bark is typically administered either by decoction (usual dosage range of 3-9 grams for a one day dose) or in prepared forms, in which the powdered or extracted herb may be included, but in quantities significantly less than the 3-9 grams per day in decoction (16). If one assumes that the total alkaloid content of magnolia bark is extracted, consumed, and absorbed, then the total magnocurarine dose at the upper level of magnolia bark use (9 grams) with highest content of magnocurarine (0.2%) is about 18 mg. This would usually be consumed over two divided doses, so 9 mg per dose.

Turbocurarine, when used as a drug, is administered in IV drip, with a dose of about 25-100 mg infused within about one minute, and then repeated as needed every 5 minutes, to yield dosing of up to several hundred milligrams over a period of as little as half an hour. Clearly, the drug level in the bloodstream will be markedly higher by these doses of alkaloid by IV drip than the orally consumed decoction, being absorbed slowly. Little is known about the extraction efficiency of the magnolia alkaloids, nor their absorption efficiency, so it is difficult to make good estimates of how large the safety margin is. For those who use high dosage decoctions, the substitute herbs with high levels of magnocurarine might be of some concern.

In finished ready-to-consume products made with magnolia bark powder or dried how water extracts, the amount of magnocurarine would be far less than in the hypothetically efficient decoction described above because of the lower amount of magnolia used. Therefore, a high safety margin is to be expected.

CONCLUSION

The insurance companies are paid by manufacturers to cover marketed formulas rather than decoctions given by Chinese medicine practitioners. Unless a specialized extraction process is utilized to extract the magnolia alkaloids, and unless these are given in high doses, the prepared forms are not a threat because of their alkaloid content. Further, the concern about renal toxicity from the 1993 Belgian report has turned out to be based on an unrelated herb and no further consideration of magnolia has been given in this regard.

Because the regulators (such as members of Health Canada) have no way to know which species of magnolia is used, or how it is prepared, or how much of the alkaloids are present, it is reasonable for there to be some lingering concerns about the alkaloid content and use of the products for pediatric applications. The products currently on the market may be entirely safe with respect to their magnolia content, yet there is not a convenient means of screening products for alkaloid content. In defending the Chest Relief formula from the warnings issued by Health Canada, Efrem Korngold and Harriet Beinfield made the estimation that the product delivered only "0.008 mg of the alkaloids" per dose, which is a miniscule amount.

This review of magnolia should provide additional reassurance that the levels of magnolia alkaloids are safe, but it also brings a caution against the unrestrained use of substitute species until they have been adequately tested. The substitutes may have similar therapeutic actions, and may even prove more effective in Chinese medical practice by virtue of having higher amounts of certain active components, but they may also present potentially toxic levels of some ingredients when the high dose preparations are utilized.

The magnolia bark on the international market has been uniform over the years, while substitution (as with Manglietia species) is only being tried out locally in some Chinese clinics. However, it is important for herb importers to observe their supplies and make sure that substitutes are not obtained for distribution unless tests are conducted on alkaloid levels. The insurance companies and government agencies, including Health Canada, need to re-evaluate the basis for the concerns they raised, and ought to change restrictions (if any are to be imposed) on use of Magnolia officinalis, which is not, in fact, high in alkaloids.

No reports of adverse reactions to magnolia bark have appeared in any of the publications of the regulatory agencies, nor in medical reports from China. In Japan, traditional formulas with magnolia are routinely used in the form of dried hot water extracts. Pinellia and Magnolia Combination (Banxia Houpo Tang) is an example of one that is frequently prescribed with magnolia bark as a main ingredient. Indications for the formula include esophageal spasms and various nervous syndromes indicating an effective antispasmodic and anxiolytic activity. In two recent studies conducted in Japan, the formula was found beneficial in treating swallowing difficulty in the elderly, improving the swallowing reflex in those who suffered from aspiration pneumonia, stroke, and progression of Parkinson's disease (17, 18). The safe use of the formula in the elderly who are in poor health, as indicated by these clinical reports, further demonstrates the safety of magnolia bark. The manufacturers of the over-the-counter herbal remedy Sublimiss specifically list the included components of honokiol, magnolol, magnoflorine, and magnocurarine, and report excellent safety for clinical evaluations conducted for them (unpublished data).

It appears unlikely that magnolia will present a risk for consumers. To the contrary, when herb product manufacturers are forced to find alternatives to magnolia bark, there is no reason to believe that the replacements will be any safer. Magnolia bark has a long history of extensive use, and its apparent safety should be welcomed.

REFERENCES

- Vanherweghem JL, et al., Rapidly progressive interstitial renal fibrosis in young women associated with slimming regimen including Chinese herbs, Lancet 1993; 34: 387-391.

- Vanhaelen M, et al., Identification of aristolochic acid in Chinese herbs, Lancet 1994; 343: 174.

- Tang W and Eisenbrand G, Chinese Drugs of Plant Origin, 1992 Springer-Verlag, Berlin.

- Zhu YP, Chinese Materia Medica: Chemistry, Pharmacology, and Applications, 1998 Harwood Academic Publishers, Amsterdam.

- Kuribara H, et al., The anxiolytic effect of two oriental herbal drugs in Japan attributed to honokiol from magnolia bark, Journal of Pharmacy and Pharmacology 2000; 52(11): 1425-1429.

- Wang SM, et al., Magnolol stimulates steroidogenesis in rat adrenal cells, British Journal of Pharmacology 2000; 131(6): 1172-1178.

- Bang KH, et al., Antifungal activity of magnolol and honokiol, Archives Pharmaceutical Research 2000; 23(1): 46-49.

- Kong CW, et al., Magnolol attenuates peroxidative damage and improves survival of rats with sepsis, Shock 2000; 13(1); 24-28.

- Wang JP, et al., Antiinflammatory and analgesic effects of magnolol, Archives Pharmacology 1992; 346(6): 707-712.

- Chiou LC, Ling JY, and Chang CC, Chinese herb constituent beta-eudesmol alleviated the electroshock seizures in mice and electrographic seizures in rat hippocampal slices, Neuroscience Letters 1997; 231(30; 171-174.

- Chiou LC, Ling JY, and Chang CC, beta-Eudesmol as an antidote for intoxication from organophophorus anticholinesterase agents, European Journal of Pharmacology 1995; 292(2): 151-156.

- Lou Zhicen and Qin Bo, Study on Quality and Systematization on Category of Chinese Frequently Used Crude Herbs, Section II, 1995 Beijing Medical University and Peking Union Medical College Allied Press, Beijing.

- Matsuki A, Recent findings in the history of anesthesiology: Discovery of muscle relaxant magnocurarine in Japan, Masui 1982; 31(12): 1414-1419.

- Xiao Peigeng (editor in chief), New Compilation of Chinese Materia Medica, Vol. III, 2000 Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences, Beijing.

- Song WZ, Cui JF, and Zhang GD, Studies on the medicinal plants of the Magnoliaceae tuhoupo of Manglietia, Journal of Chinese Herbs 1989; 24(4); 295-299.

- Pharmacopoeia Commission of PRC, Pharmacopoeia of the PRC, (English edition) 1988 People's Medical Publishing House, Beijing.

- Iwasaki K, et al., The effects of the traditional Chinese medicine Banxia Houpo Tang on the swallowing reflex in Parkinson's disease, Phytomedicine 2000; 7(4): 259-263.

- Iwasaki K, et al., Traditional Chinese medicine Banxia Houpu Tang improves swallowing reflex, Phytomedicine 1999; 6(2): 102-106