REHMANNIA

Rehmannia refers to the root of Rehmannia glutinosa (see Figure 1), an herb of the Scrophulariaceae family. The species name glutinosa comes from glutinous, referring to the sticky nature of the root. Rehmannia is closely related to another herb that carries the name of the plant family, Scrophularia ningpoensis (see Figure 2), for which the root is also used in China. The claimed therapeutic effects and recommended uses of the two herbs are quite similar, but rehmannia is far more frequently prescribed. Also in this plant family is Picrorrhiza kurrooa (see Figure 3), for which the root is used in Chinese medicine; some of its actions are related to those of the other two herbs (1).

Rehmannia was known as dihuang (meaning earth yellow, or underground yellow) and disui (earth marrow) at the time the Shennong Bencao Jing was written (ca. 100 A.D.). It was included in this text among the superior class herbs, with this description (2):

Rehmannia is sweet and

cold. It mainly treats broken bones,

severed sinews from falls, and damaged center.

It expels blood impediments, replenishes bone marrow, and promotes growth

of muscles and flesh. When used in

decoctions, it eliminates cold and heat accumulations and gatherings, and

impediment. Using the uncooked is

better. Protracted taking may make the

body light and prevent senility.

This description indicates

that rehmannia was deemed an herb of restoration—repairing broken bones,

severed sinews, damaged center, debilitated bone marrow, and wasted muscles and

flesh—even in the uncooked form. In

addition, it could help get rid of impediments, accumulations, and gatherings,

indicating that it would resolve swellings and masses. Despite this depiction of its properties,

rehmannia soon became better known for treating fevers and bleeding. In modern times, rehmannia is especially

used for treating hormonal disorders, such as menopause (see: Treatment of menopausal syndrome with

Chinese herbs), thyroid imbalance (see: Treatments

for thyroid disorders with Chinese herbal medicine), and adrenal

insufficiency.

Scrophularia

was listed in the same text, and known as xuanshen

(black shen, a name directly linking

it to ginseng, which was man-shaped shen,

also classified as the yellow shen in

the five elements system). Another

early name for this herb was chongtai

(multi-story platform; referring to its leaf pattern). Scrophularia was included in the middle

class of herbs, with this description:

Scrophularia is bitter

and slightly cold. It is non-toxic,

treating mainly cold and heat accumulations and gatherings in the abdomen, and,

in females, postpartum illnesses and illnesses related to breast feeding. It supplements the kidney qi and brightens

the eyes.

The overlap between the properties of these two herbs includes their cold nature, their ability to treat cold and heat accumulations and gatherings, and their non-toxic quality (implied for rehmannia by its classification in the upper class). The term xuanshen, which is still used today, is taken from the concept that this herb has a quality somewhat akin to that of ginseng (see: Notes on the term “shen” in renshen), and that it is especially beneficial to the kidney (hence the statement that it supplements the kidney qi), which is of the water element and associated with the color black (xuan). The fact that rehmannia could benefit the marrow—a part of the body that is described in traditional Chinese medical terms as an extension of the kidneys—again illustrates some connection between these herbs. Both have a dark brown color, nearly black.

In many herbal prescriptions that contain scrophularia, rehmannia is also present (3). In fact, it appears that rehmannia and scrophularia have similar therapeutic actions and that rehmannia is the more potent of the two, therefore being used more frequently. It can be suggested that the Chinese herbalists understand that when administering a formula with scrophularia, one can get a better effect by including rehmannia.

CONTENTS AND NATURE OF REHMANNIA

A. The Cloying Nature of Rehmannia

One of the features of rehmannia that is frequently mentioned is its “cloying” nature (a term elected by Bensky and his colleagues (4, 5)). A dictionary definition of cloy is “to supply with too much of something, especially with something too rich or sweet.” The word is also short for the obsolete term accloy, which means to clog or satiate. Other authors describe the nature of rehmannia as “sticky” or “heavy.” The root, especially the one that has been steamed (shu dihuang, or cooked rehmannia) is dense, sticky, sweet, and, when taken in large doses, hard to digest. Its physical properties of density and stickiness, according to traditional physicians, indicate a function in the body: namely to settle the erratic qi that is uncontrolled by the kidney (and liver). Its heaviness helps it draw the qi downward to the lower warmer from which it can then rise in a more orderly fashion along standard pathways; the stickiness helps it draw the scattered qi together, so that it sticks to its intended pathways.

Chemical analysis of rehmannia explains much about the cloying nature. The main components of rehmannia decoction (6) are simple sugars (including glucose, galactose, fructose, sucrose, and mannitol), which make the root sticky and give it the sweet taste that is mentioned in the Shennong Bencao Jing, and stachyose, an indigestible starch, which, when taken in large quantity, makes the root cause gas and bloating (stachyose is the component of beans that has this same effect).

Table 1. Sugar and polysaccharide content of rehmannia roots. Note that about half the content of dried

rehmannia is stachyose and verbascose, polysaccharides that are difficult to

digest.

|

Sugar |

Fresh (%) |

Dry (%) |

|

Stachyose |

62.7 |

47.8 |

|

Raffinose |

3.6 |

8.7 |

|

Sucrose |

2.8 |

8.1 |

|

Galactose |

3.1 |

5.3 |

|

Verbascose |

4.6 |

4.3 |

|

Manninotriose |

1.0 |

4.2 |

|

Fructose |

1.9 |

3.1 |

|

Mannitol |

7.4 |

3.0 |

|

Glucose |

1.7 |

2.2 |

When rehmannia is taken in a formula in the form of small pills, a common method of administering the tonic preparations, it does not cause a digestive problem and the “cloying” quality is not especially obvious because of the low dosage ingested. However, Chinese doctors commonly prescribe 12–30 grams and up to 60 grams of rehmannia in decoction for one day, sometimes taken in one dose per day for the heat-cleansing anti-hemorrhage formulas, which yields a large amount of the sugars and stachyose. Or, they prescribe rehmannia-based honey boluses (e.g., Rehmannia Six Formula) in the dose of 9 grams at a time; the honey together with the rehmannia can produce quite a “heavy” sensation in the digestive system. In such forms of administration, the large amount of sugar can make one feel nauseated (soon after consuming it), and the large amount of stachyose and verbascose can make one feel bloated (after about an hour); hence, the reported “cloying” quality and difficulty digesting the herb. It has been reported that simple sugars are present in very large amounts in the decoction made from cooked rehmannia (the more cloying form): more than three times as much as in decoctions made from raw rehmannia (the less cloying form). Presumably, the steaming process that yields cooked rehmannia breaks down the ordinary starches in the root to simple sugars.

One method said to be useful for dealing with the cloying nature of rehmannia is to include the herb alisma in a formula. For example, the role of alisma in Rehmannia Six Formula has been described this way (16): “Alisma clears and purges kidney fire and prevents the greasy-indigestion of rehmannia.” At this time, there is no known basis for regarding alisma as a remedy for the effects of the sugars or starches introduced by rehmannia. In fact, virtually all the rehmannia-based formulas that are not directly related to Rehmannia Six Formula (see below) do not include alisma. Several derivatives of the traditional formulation made by a combination of deletions and additions, have alisma deleted, implying it is a non-essential ingredient in relation to rehmannia. Presumably, this particular action of alisma was described as an afterthought to explain its inclusion in the well-known rehmannia formula and similar ancient prescriptions where it appears to have served, instead, a role as a diuretic. Similarly, the herbs citrus, cardamon, ginger, and saussurea, all used for dispersing stagnant qi and moisture, are said to counteract the cloying property of rehmannia, but these, too, rarely appear in formulas with rehmannia. Still, there may be some basis for the claim that these spicy herbs aid in dealing with the indigestible quality of rehmannia; they contain components that reduce intestinal peristalsis (especially citrus) and help break up intestinal gas, thus alleviating some of the effects of stachyose.

B. The Anti-Inflammatory and Tonic Aspects of Rehmannia

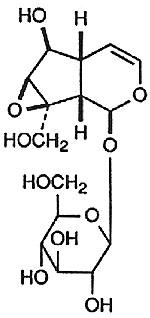

The main active constituents of rehmannia are iridoid glycosides. These are monoterpenes that have a glucose molecule attached. Catalpol (see Figure 4) was the first of these isolated from rehmannia (in 1969), and is the one present in largest amounts. There are more than a dozen iridoids that have been isolated from rehmannia (6), but the others are present in relatively minor quantities. In a study of several samples of rehmannia (17), it was found that catalpol makes up about 3–11% of the undried root content (depending on the growing conditions), with considerably less (about 1–2%) in the dried root: the drying process evidently destroys this component, converting it into another compound that may or may not be active.

The pharmacological action of catalpol and the other iridoids is not fully established, but it appears that their main function is to stimulate production of adrenal cortical hormones (7). These hormones have anti-inflammatory action (explaining the claimed benefits of rehmannia for asthma, skin diseases, and arthritis) and are involved in the production of sex hormones (explaining the claimed benefit of treating menopause, impotence, and other signs of hormone deficiency). It is possible that anti-inflammatory effects could explain its early use in mending injuries, and the androgens that the adrenal gland might yield could increase the muscles, thus helping to explain the earliest reported properties of rehmannia.

Since 1965, a group at the

Shanghai Medical College has been using rehmannia-based kidney tonic formulas

to treat bronchial asthma. In a 1982

report (13), they described using three formulas, Rehmannia Six Formula (Liuwei Dihuang Wan), Rehmannia and

Anemarrhena Formula (Da Buyin Wan),

and their self-designed “kidney reinforcing regimen,” with Wenyang Tang (a derivative of Rehmannia Six Formula). They reported that it would increase the

daily excretion of 17-hydroxycorticosteroid (17-OHCS), which indicates higher

production of adrenal steroids.

The adrenal steroids may then serve as precursors to production of sex hormones. Rehmannia Eight Formula (Bawei Dihuang Wan) was tested in aged rats (18). It was shown to increase estradiol level of the serum in female rats and to raise serum testosterone in male rats. A formula called Bushen Shengxue No. 1 (tonify the kidney, produce blood), is made with raw rehmannia, astragalus, gelatin, and tortoise shell gelatin. In mice, this formula increased the body weight and increased plasma testosterone (19). The combination of raw rehmannia, anemarrhena, plus licorice was fed to rats who were administered dexamethasone for two months (20); this drug impairs adrenal function. The herbs promoted growth, lowered plasma glucose, decreased plasma-free fatty acids, and increased plasma cortisone, suggesting a protective effect for the adrenals.

Catalpol gets its name from the plants of the genus Catalpa, which contains a similar ingredient, isolated in 1963. These plants are in a different plant family (Bignoniacea) than rehmannia. Two species of Catalpa appeared in the Shennong Bencao Jing, the bark of Catalpa bungei (zibaipi) and the fruit of Catalpa ovata (listed under xinbaipi, currently known as xingu); the latter was only mentioned in that text in passing. These are rarely used today. In the Shennong Bencao Jing, Catalpa bungei is listed as an inferior-grade wood herb, but its basic properties are similar to that of scrophularia (bitter and cold), and the text mentions that “If fed to pigs, the pigs may grow four times larger.” This coincides with the claim made for rehmannia that it builds up the flesh and muscles, which may be a response to the iridoids. This effect has not been researched, though one of the studies cited above mentioned that a rehmannia-based formula increased the animals’ body weight. There is a precedent for such traditional claims being verified. Lycium fruit, which is frequently used with cooked rehmannia to build up the flesh and muscles in persons suffering from wasting diseases, contains betaine, a substance that is used by the poultry industry to aid the growth of chickens and is now used as a supplement by American weight lifters to increase their muscle mass (see: Lycium fruit).

Scrophularia contains iridoid glycosides as well, including harpagoside, harpagide, aucubin, verbenalin, ajugol, and longanin. Several iridoids were evaluated for their anti- inflammatory activity on two laboratory animal models: the carrageenan-induced mouse paw edema and the TPA-induced mouse ear edema. Loganic acid was the most active (44% edema inhibition) on the former test, whereas the catalpol derivative mixture isolated from scrophularia, showed the highest activity (72–80% edema inhibition) on the latter (24).

Another commonly used Chinese herb that contains iridoid glycosides as one of its main active ingredients is gardenia (shanzhizi). The main glycoside is geniposide. It is known that this glycoside stimulates bile secretion, which can have a laxative effect. If catalpol has a similar action, then this may further explain (along with the stachyose content) why rehmannia is usually contraindicated in cases of diarrhea. Like rehmannia and scrophularia, gardenia is used to treat bleeding associated with a heat syndrome and ulceration of the mucus membranes. It has been reported that extract of rehmannia hastens the coagulation of blood (1) and this is presumably an effect of the iridoid glycosides. Rehmannia and gardenia appear together in the traditional formula Tang-kuei and Gardenia Combination (Wenqing Yin), which is mainly used to treat bleeding (uterine bleeding, excessive menstruation, bleeding due to gastric ulcers, occult bleeding, etc.). The famous woman’s formula Bupleurum and Tang-kuei Formula (Xiaoyao San) has two variants that are used when there is excessive uterine bleeding: one adds gardenia and moutan, and the other adds rehmannia to the basic prescription. Evidently, gardenia and rehmannia help treat bleeding. Rehmannia and gardenia appear together in the formula Gentiana Combination (Longdan Xiegan Tang), commonly used for inflammation of the vagina and urinary tract, suggesting that they reduce inflammation.

Several species of vitex are used in Chinese medicine and contain iridoid glycosides. Interestingly, vitex, gardenia, and rehmannia are deemed beneficial to the vision. They appear together in traditional vision improving formulas such as Gardenia and Vitex Combination (Xi Gan Mingmu Tang) and Crysanthemum Combination (Zi Shen Mingmu Tang). The mechanism of action is unclear.

A European vitex, V. agnus-castus, known commonly as chaste tree fruit or chaste berry, contains the iridoid glycosides agnuside and aucubin as the main active ingredients. The herb is reputed to normalize irregular menstrual cycles and to treat amenorrhea and dysmenorrhea. In addition, it is used to alleviate menopausal symptoms. Today, herbalists also prescribe it for premenstrual tension. It is believed to have an effect on luteinizing hormone and follicle stimulating hormone.

One of the iridoid glycosides that is found in small amounts in rehmannia and scrophularia is aucubin. It is very similar to catalpol and is also an active ingredient of the rarely used herb Acuba japonica, a close relative of cornus (which contains secoiridoid glycosides) that is used in many rehmannia formulas; aucubin is also present in the more commonly used plantago seed. Both aucubin (14) and geniposide (15) have been shown to have liver-protective actions.

Rehmannia and scrophularia have been shown to have a weak anti-diabetic effect (see: Treatment of diabetes with Chinese herbs), with rehmannia having a stronger action than scrophularia. The iridoid glycosides have been shown to be the source of this action.

C. Processing of Rehmannia

There are several forms of rehmannia mentioned in the Chinese medical literature (11, 25), two of which are readily available to practitioners today. When the fresh root (xian or xiansheng) is collected, it may be put into decoction with herbs, or it may be juiced to yield rehmannia juice (xian zhi), which was used in ancient times and is rarely mentioned today. The fresh herb and its juice are preferred in treatment of bleeding due to heat syndrome. The fresh root may be subjected to minimum drying, sometimes by burying in warm sand. This material is still used in China, but because it is not possible to maintain this moist material in good condition on the herb market, it is not available for general use. It is especially used to relieve thirst and frequent urination in cases of feverish disease. The two forms that are generally available to practitioners everywhere are dried rehmannia root (gan dihuang or gansheng dihuang, commonly referred to as sheng dihuang, and, in English, usually called raw rehmannia), and cooked rehmannia root (shu dihuang). Raw rehmannia root has been dried—in the sun or using an oven—to the point that it preserves well, and cooked rehmannia root is currently prepared by soaking it in a solution of water and rice wine (30%) and steaming it for eight hours (sometimes a full day).

The earliest description of cooked rehmannia (21) is in the Leigong Paochi Lun (possibly from the 5th century A.D.):

Following the collection of fresh rehmannia, remove the white fuzz, then steam the plant on a willow-wood boiler above a porcelain pot; after a certain time, open the cover to allow the steam to escape. Now mix the drug with wine, steam it once more, and again allow the steam to escape after a while. The drug should then be dried. It must not be damaged by coming into contact with copper or iron.

This treatment was sometimes applied repeatedly, up to nine times to mimic the alchemical transformation methods that were applied to cinnabar and numerous elixirs. For example, in the Bencao Gangmu, published at the end of the 16th century, it was reported that (22):

Shu dihuang is made by taking juicy roots, washing in spirits, filling with the seeds of cardamon (suoshami), steaming on a willow frame in a porcelain vessel, drying, and resteaming and redrying nine times.

Cardamon seeds may have contributed to the warming quality desired in the finished product, or may have been thought to protect the user from the cloying effect of cooked rehmannia. The darkness of the processed rehmannia root may be partly due to oxidation of the iridoid glycosides.

According to traditional practitioners, while rehmannia juice and fresh rehmannia are best at purging fire, the (dried) raw rehmannia root has somewhat less of this property, but is able to nourish yin, blood, and essence (i.e., benefit the marrow). The cooked root is no longer of cold property, but is slightly warm, it loses its ability to purge fire, but gains in ability to nourish yin and blood. The dried root can be further processed by frying the root (scorching), which is said to make it more suited to blood deficiency fever (rather than yin deficiency fever), or by charring it, which is suited to treating bleeding (applied for the syndrome of yin deficiency bleeding, whereas the fresh rehmannia juice is applied for the syndrome of excess-fire-induced bleeding). Similarly, cooked rehmannia root can be subjected to scorching or carbonizing, the former used to nourish blood and the latter to treat blood-deficiency bleeding.

At this time, there is little evidence, chemical, pharmacological, or clinical, to support the claims of changes in the properties of the root as the result of different processing. It has been reported, as mentioned above, that the cooked root has more simple sugar than the other forms (which may have little influence on its effects) and that the dried root has more simple sugars and less polysaccharide than the freshly picked root, but little work has been done to associate chemical changes with alterations in pharmacological properties. In a review of research on selected herbs first reported in 1975 (12), it was mentioned that raw and cooked rehmannia were compared by the method of thin layer chromatography, which revealed that there were apparent differences in the quantities of ingredients extractable by various solvents between these two rehmannia products, but there was no obvious change in the substances present.

D. Literature on Chemical Constituents and Pharmacology

The Chinese literature reveals a remarkable lack of active investigation of rehmannia’s constituents and pharmacology in light of the predominance of rehmannia in formulas administered for a wide range of disorders. Only rare reports describe the chemical components, possibly because it is felt that there are no new ones to be found. None of the known active constituents appear to have been subjected to intensive pharmacological study in China, though interest has developed in the West as a result of analysis of Western herbs with similar constituents. Rehmannia extracts are occasionally tested in laboratory animals, but far more often, rehmannia is a component of a large formula that is being tested. In clinical trials, rehmannia is frequently included, but the formulations are typically quite large (typically 8–15 ingredients), so that the role of rehmannia in the reported clinical effects remains unclear.

Scrophularia is even less researched than rehmannia. Its chemical constituents were investigated more than thirty years ago by Japanese researchers, but little has been done since. Similarly, pharmacological actions of its extract or isolated constituents are not actively investigated. As with rehmannia, when used in clinical trials, it is usually in very large formulas (often with rehmannia included). Catalpa species remain uninvestigated.

As

a result of this scarcity of reports, while the existing literature points to

certain pharmacological actions of rehmannia, it is somewhat difficult to

assess the effects reliably. The most

widely studied rehmannia-based formula, Rehmannia Six Formula, is still

inadequately tested. According to Li

Ling, who carried out a literature review (10) including 36 journal articles

published from 1983–1994:

Rehmannia Six Formula has been widely used in clinical practice, representing the principle of treating different diseases with the same therapeutic method. This recipe is worth further study, but the research is still in the area of documenting usual clinical experience and falls short of systematic study.

REHMANNIA IN TRADITIONAL FORMULAS

The earliest text to include rehmannia in formulas with explanations for their use was the Shanghan Zabing Lun (220 A.D.). This work fell into relative obscurity until it was reconstructed and revitalized during the Song Dynasty (around 1000 A.D.). The book was then divided into two separate works, Shanghan Lun and Jingui Yao Lue. The former described an epidemic disease and its treatment by herbs, and the latter dealt with miscellaneous disorders. Rehmannia was a relatively minor herb in these books.

Only one of the 110 formulas of the Shanghan Lun contained rehmannia: Baked Licorice Combination (Zhi Gancao Tang). This formula, like several later ones that contain rehmannia, also has ophiopogon, a yin-nourishing herb. Baked Licorice Combination is still used today. The traditional indications include lingering fever (after a feverish disease) in the palms and soles, dry mouth, dry skin, heart palpitations, and shortness of breath.

In the Jingui Yao Lue, only 6 of the 205 formulas included rehmannia, and only three of those remain in use today. Except for one of the formulas, each of those was mentioned but once in the text. This relatively infrequent use suggests that rehmannia was not a very important to the author of the Shanghan Zabing Lun. Of the three formulas still used today, one is widely used: Rehmannia Eight Formula, some times called Jingui Bawei Tang (Eight Flavor Tea from the Jingui). This is the formula that was mentioned repeatedly in the Jingui Yao Lue, in each statement, it was indicated for a disorder of urination: twice for treating urinary frequency and twice for inhibited urination.

A few centuries after the writing of the Shanghan Zabing Lun came the Zhong Zang Jing. This book has been attributed to Hua Tuo, but was probably written by another, or several other authors, between 300 and 500 A.D. The book presents 68 formulas; 8 of those formulas included rehmannia; one formula has rehmannia as a single herb and two formulas have it in combination with only one other herb. Thus, by this time, rehmannia was clearly a significant herb.

During the Song Dynasty (900–1100 A.D.), a book of popular prescriptions was produced that had several rehmannia formulas: this was the Taiping Huimin Hejiju Fang, often known simply as the Hejiju Fang. In particular, this book listed Tang-kuei Four Combination (Siwu Tang), for which rehmannia represents one-quarter of the prescription; this formula remains the central liver-blood nourishing formula of modern Chinese medicine.

As important as the Hejiju Fang was to encouraging the use of rehmannia for all future generations, another work also led to heavy reliance on rehmannia in prescriptions. It was a book of prescriptions for treating children, Xiaoer Yaozheng Zhijue, published a few years after the Hejiju Fang. This book presented Rehmannia Six Formula (Liuwei Dihuang Tang), a derivative of Rehmannia Eight Formula made by eliminating the two kidney-warming herbs cinnamon bark and aconite. The modified formula was designed originally to treat children who had lack of spirit (poor mental function, low energy), shiny, pale, complexion, and inhibited development, such as unclosed anterior fontanel. The application is quite different than the dominant use of the formula today, which is for older persons who are suffering from degenerative conditions, especially when there is a urinary disorder. Yet, the underlying principle of treatment, nourishing the yin, has not changed.

Tang-kuei Four Combination and Rehmannia Six Formula became central prescriptions for the development of numerous formulas, some of which are so important that they are listed as separate traditional prescriptions and not just variations that can be made.

VARIATIONS ON REHMANNIA SIX FORMULA

Nourish Liver and Kidney, Settle Agitation Variations of Rehmannia Six Formula

|

Rehmannia Six Formula |

Lycium, Chrysanthemum, Rehmannia Formula |

Magnetite and Rehmannia Formula |

Magnetite, Acorus, and Rehmannia Formula |

|

Rehmannia Dioscorea Cornus Alisma Hoelen Moutan |

Rehmannia Dioscorea Cornus Alisma Hoelen Moutan Lycium Chrysanthemum |

Rehmannia Dioscorea Cornus Alisma Hoelen Moutan Magnetite Bupleurum |

Rehmannia Dioscorea Cornus Alisma Hoelen Moutan Magnetite Acorus Schizandra |

Benefit Lung and Astringe Surface Variations of Rehmannia Six Formula

|

Rehmannia Six Formula |

Schizandra and Rehmannia Formula |

Schizandra, Ophiopogon and Rehmannia

Formula |

Rehmannia and Astragalus Formula |

|

Rehmannia Dioscorea Cornus Alisma Hoelen Moutan |

Rehmannia Dioscorea Cornus Alisma Hoelen Moutan Schizandra |

Rehmannia Dioscorea Cornus Alisma Hoelen Moutan Schizandra Ophiopogon |

Rehmannia Dioscorea Cornus Alisma Hoelen Moutan Schizandra Astragalus |

Clear Deficiency Heat Variations of Rehmannia Six Formula

|

Rehmannia Six Formula |

Anemarrhena, Phellodendron and Rehmannia

Formula |

Rehmannia and Tortoise Shell Formula |

Hidden Tiger Formula |

|

Rehmannia Dioscorea Cornus Alisma Hoelen Moutan |

Rehmannia Dioscorea Cornus Alisma Hoelen Anemarrhena Phellodendron |

Rehmannia Anemarrhena Phellodendron Tortoise shell |

Rehmannia Anemarrhena Phellodendron Tortoise shell Peony Tiger bone Cynomorium Ginger Citrus |

Nourish-Essence Variations of Rehmannia Six Formula

|

Rehmannia Six Formula |

Rehmannia and Lycium Combination |

Rehmannia and Eucommia Combination |

Achyranthes and Rehmannia Formula |

|

Rehmannia Dioscorea Cornus Alisma Hoelen Moutan |

Rehmannia Dioscorea Cornus Hoelen Lycium Baked Licorice |

Rehmannia Dioscorea Cornus Lycium Baked Licorice Eucommia Tang-kuei Ginseng |

Rehmannia Dioscorea Cornus Lycium Achyranthes Cuscuta Tortoise shell Antler gelatin |

Yang-invigorating and Yang-restoring Variants of Rehmannia Six Formula

|

Rehmannia Six Formula |

Rehmannia Eight Formula |

Plantago and Achyranthes Formula |

Rehmannia and Schizandra Formula |

||

|

Rehmannia Dioscorea Cornus Alisma Hoelen Moutan |

Rehmannia Dioscorea Cornus Alisma Hoelen Moutan Aconite Cinnamon |

Rehmannia Dioscorea Cornus Alisma Hoelen Moutan Aconite Cinnamon Plantago Achyranthes |

Rehmannia Dioscorea Cornus Alisma Hoelen Moutan Aconite Cinnamon Schizandra Deer antler |

||

|

Rehmannia and Aconite Combination |

Rehmannia and Cuscuta Combination |

||||

|

Rehmannia Dioscorea Cornus Aconite Cinnamon Lycium Eucommia Baked licorice |

Rehmannia Dioscorea Cornus Aconite Cinnamon Lycium Eucommia Antler gelatin Cuscuta |

||||

VARIATIONS ON TANG-KUEI FOUR COMBINATION

Blood-Vitalizing Derivatives of Tang-Kuei Four Combination

|

Tang-kuei Four

Combination Siwu Tang |

Persica and Carthamus

Combination Tao Hong Siwu Tang |

Persica and

Achyranthes Combination Xuefu Zhuyu Tang |

|

Rehmannia Tang-kuei Cnidium Peony |

Rehmannia Tang-kuei Cnidium Peony Persica Carthamus |

Rehmannia Tang-kuei Cnidium Peony (red) Persica Carthamus Achyranthes Chih-ko Licorice Bupleurum Platycodon |

Qi- and Blood-Nourishing Variants of Tang-Kuei Four Combination

|

Tang-kuei Four Combination |

Tang-kuei and Ginseng 8 Combination |

Ginseng and Tang-kuei Ten Combination |

Ginseng Nutritive Combination |

|

Rehmannia Tang-kuei Cnidium Peony |

Rehmannia Tang-kuei Cnidium Peony Ginseng Atractylodes Hoelen Licorice |

Rehmannia Tang-kuei Cnidium Peony Ginseng Atractylodes Hoelen Licorice Astragalus Cinnamon |

Rehmannia Tang-kuei Peony Ginseng Atractylodes Hoelen Licorice Astragalus Cinnamon Schizandra Citrus Polygala |

Nourish Blood, Clear Heat Variations of Tang-Kuei Four Combination

|

Tang-kuei Four Combination |

Coptis, Picrorrhiza, and Tang-kuei

Combination |

Tang-kuei and Gardenia Combination |

Bupleurum and Rehmannia Combination |

|

Rehmannia Tang-kuei Cnidium Peony |

Rehmannia Tang-kuei Cnidium Peony Coptis Picrorrhiza |

Rehmannia Tang-kuei Cnidium Peony Coptis Gardenia Scute Phellodendron |

Rehmannia Tang-kuei Cnidium Peony Coptis Gardenia Scute Phellodendron Bupleurum Forsythia Arctium Trichosanthes root Siler Licorice |

A final boost to the use of rehmannia in prescriptions was given by the publication of Wenbing Tiaobian (1798 A.D.), an influential text about the treatment of feverish diseases (8). This book, and others on the topic produced around the same time, yielded several heat cleansing and moistening formulas that contained rehmannia and scrophularia.

In the book Commonly Used Chinese Herb Formulas, Companion Handbook (9), which, to a large extent, reflects traditional formulas that are still being used today, more than 15% of all the prescriptions contain rehmannia. Thus, of the thousands of prescriptions that have been recorded, it appears that formulas with rehmannia have been preferentially retained. New prescriptions developed for Western practitioners of Chinese medicine similarly reflect the current Chinese preference for rehmannia (see Analysis of formulas used in Western practice of Chinese medicine).

REHMANNIA AS A MAIN HERB IN A FORMULA

Rehmannia

is included in many formulas that have numerous ingredients; its role in the

larger formulas may be questioned, as there are so many ingredients producing

various health effects. In the small

formulations, where rehmannia is provided in a large dosage (typically 12

grams/day or more in decoction) and where it makes up a substantial part of the

formulation (at least 20%), the indications and uses for the formula as a whole

may well reflect the action of rehmannia.

These formulas, with from 1 to 6 ingredients, are described below.

1. Single-herb rehmannia. In the Zhong Zang Jing is Shaman’s Rehmannia Decoction Worth a Thousand Gold (Zuoci Zhenren Qianjin Dihuang Jian), which is made by combining juice of fresh rehmannia with powder of cooked rehmannia, to be made into pills. It is simply said that long administration of these pills makes one “abstemonious from desires and offers an immortal’s imperishable life.” This tells us that the herb was respected as a tonic for longevity and was considered suitable for long-term administration. This is one of the qualifications for being listed as an upper-class herb. We know now that the rehmannia juice is rich in the iridoid glycosides, and it may be of interest that this preparation did not rely solely on cooked rehmannia.

2. Two-herb formulas. The Zhong Zang Jing lists two prescriptions with only two herbs: Rehmannia and Chih-ko Formula (Zhi Furen Xuebeng Fang), which is made with powdered herbs—1 part chih-ko (a type of citrus) and 2 parts rehmannia—to be swallowed down with diluted vinegar. This was used to treat profuse uterine bleeding. The other was Rehmannia Juice and Lacca Formula (Zhi Furen Xuebi Fang), which was made with lacca (ganqi; a toxic herb) and fresh rehmannia juice. This was boiled down to a paste, with a small amount dissolved in wine and taken. This formula was indicated for blockage of blood flow, such as occurs with amenorrhea. This latter use corresponds with the original indication of rehmannia as expelling blood impediments. The treatment of uterine bleeding represents a new indication (compared to the description in the Shennong Bencao Jing), which is elaborated upon in some of the larger formulas. One of the traditional theories of using rehmannia to treat bleeding is that heat in the blood causes the blood to run wild and overflow the vessels; rehmannia clears the heat and thus stops the bleeding. Neither of these two herb formulas are used today. Another prescription of two herbs is Rehmannia Decoction (Dihuang Jian); a large formula by this name is mentioned in Zhong Zang Jing, but this particular formula is from a later text. It combines raw rehmannia with deer antler glue and is indicated to nourish blood and stop bleeding, mainly to be used in cases of lung disease with hemoptysis. Gelatins, whether from deer antler, tortoise shell, or donkey hide, have hemostatic properties.

3. Three-herb formulas. The Jingui Yao Lue has a formula with rehmannia plus sophora and scute: Scute Three Herb Combination (Sanwu Huangqin Tang), which is traditionally used for treating bleeding (mainly uterine bleeding) that leads to fatigue, feverish sensation, and hot and dry conditions (especially at night). In this case, scute contains anti-bleeding flavonoids. This formula is still in use today, treating inflammatory conditions of the skin (eczema, urticaria), menopausal disorders (e.g., hot flashes, irregular bleeding), and postpartum fever. In the Wenbing Tiaobian, a formula comprised of rehmannia, scrophularia, and ophiopogon (Zengye Tang), was presented for treatment of a heat syndrome that caused deficiency of fluids, with symptoms of fever, thirst, and constipation. This formula is today indicated for treatment of constipation associated with intestinal tuberculosis and other diseases.

4. Four-herb formulas. Sun Simiao wrote about herbal formulas during the period 300–500 A.D. (the same time as the Zhong Zang Jing), and designed the Rhino and Rehmannia Combination (Xijiao Dihuang Tang), which combines the two named ingredients with two types of peony: red peony and moutan. This formula is used to clear heat and toxin and stop bleeding. The traditional indications include diseases that produce hemoptysis, nosebleeds, and other bleeding that accompanies a fever, and also for mental confusion during a febrile disease. Today, rhino horn is substituted by buffalo horn and the formula is used for treating various types of bleeding.

In Xiaoer Yaozheng Zhijue, the book that introduced Rehmannia Six Formula as a treatment for young children, the formula Dao Chi San, Rehmannia and Akebia Formula, was introduced. It contains rehmannia, akebia, licorice, and lophatherum (a type of bamboo). The formula name indicates that it is a powder taken to eliminate red, and the redness refers to flushed face and redness and ulceration in the mouth. Today, the formula is used both for oral ulceration and for acute cystitis. The formula is applied to treat a fire syndrome that affects the heart and/or small intestine.

In the book Danxi Xinfa, the formula Da Buyin Wan was presented. This pill has four herbal ingredients, though there is a fifth ingredient when making pills (bone marrow from pig’s vertebrae). The four standard ingredients are cooked rehmannia, tortoise shell, anemarrhena, and phellodendron. This formulation is intended to treat feverish feeling and sweating, possibly accompanied by hemoptysis. Such symptoms often accompany severe cases of tuberculosis (see Chin-chiu and Tortoise Shell Formula, below). It has also been applied to hyperthyroid conditions, since the overactivity of thyroid yields signs of heat and agitation similar to those of the infectious diseases.

A formula developed for treatment of nasal bleeding combines raw and cooked rehmannia with charcoaled tang-kuei, lotus leaf, and lycopus. It is used when a feverish disease damages the yin, and causes the nasal passages to become dry, with resultant nose bleeding. A formula for hemoptysis and epistaxis (bleeding from the stomach) is Si Sheng Wan, comprised of raw rehmannia, lotus leaf, artemisia, and biota tops. All parts of the lotus are used for hemostatic effects.

The other significant four-herb formula is Siwu Tang, which combines rehmannia with tang-kuei, peony, and cnidium. This formula is traditionally used to treat weakness that is due to blood loss or fever due to blood deficiency (see Sanwu Huangqin Tang above, used as a treatment during the blood loss when the same symptoms arise). It is especially used as a woman’s formula to treat irregular menstruation, uterine bleeding (also, rectal/anal bleeding), and other disorders.

5. Five-herb formulas. Two of these herb formulas with rehmannia were used primarily for oral ulceration. These are Rehmannia and Gypsum Combination (Yunü Jian; Decoction of Fair Maiden), which combines cooked rehmannia with gypsum, ophiopogon, anemarrhena, and achyranthes, and Coptis and Rehmannia Formula (Qingwei San; Clear Stomach Heat Powder), which combines raw rehmannia with tang-kuei, moutan, cimicifuga, and coptis. Both formulas clear stomach heat and blood heat. The former nourishes yin and stops bleeding and the latter removes redness. Both are used today for treating gum disease and oral ulceration.

Another prescription,

Ching-hao and Turtle Shell Combination (Qinghao

Biejia San), is a prescription from the Wanbing Tiaobian. This formula combines raw rehmannia with

turtle shell, anemarrhena, ching-hou, and moutan. It is said to clear heat, cool blood and nourish yin and was

developed to treat the late stage of a feverish disease that had already

damaged the yin and left a persisting low-grade fever. Today, it has similar uses, given to

patients with chronic persisting diseases such as pulmonary tuberculosis and

viral hepatitis; it has also been applied to treat hyperthyroidism. In the same book, Yiwei Tang was presented.

It contains raw rehmannia, ophiopogon, lycium fruit, yu-chu, and crystal

sugar. This formula treats feverish

disease with oral ulceration. It was

modified later to produce a six-ingredient formula (Yiguan Jian; see below) substituting crystal sugar with tang-kuei

and melia to regulate the liver qi.

A formula for a condition dominated by heat and intestinal dryness (with severe constipation) is Zengye Chengyi Tang. This formula combines raw rehmannia with scrophularia and ophiopogon to moisten dryness and rhubarb plus mirabilitum to purge the congested intestines.

The book Zhengshi Zhunsheng has a three ingredient tonic pill called Zhujing Wan (Preserve the Sights Pill), made with cooked rehmannia, cuscuta, and plantago seed, which is to be taken with a two ingredient decoction made with hoelen and acorus, to yield a five-ingredient formula. The purpose of this formula is to nourish the kidney and liver in order to promote good vision. Hoelen and plantago drain excess fluids that may contribute to accumulation of turbidity in the fluid compartment of the eye (these ingredients are included in modern formulas for treating glaucoma). Similarly, acorus is used to clarify the obscurities and is traditionally used to brighten the vision and intelligence. Rehmannia and cuscuta are here used as tonics for the kidney and liver.

6. Six-ingredient formulas. There are two key kidney-nourishing formulas that use rehmannia. One is Rehmannia Six Formula and the other is Zuogui Yin (Decoction to Restore the Left Kidney; the left is the yin side). Both formulas contain rehmannia, dioscorea, hoelen, and cornus; the latter replaces moutan and alisma with lycium fruit and baked licorice. The ingredients of Rehmannia Six Formula are sometimes described as being three pairs of tonifying/purging herbs. Thus, rehmannia nourishes the kidney fluids while alisma drains water; dioscorea nourishes the spleen yin while hoelen purges spleen dampness; and cornus nourishes the liver while moutan purges liver heat and liver blood stagnation. To yield the derivative formula Zuogui Yin, two of the “purging” herbs are removed and replaced by two tonic herbs: lycium fruit nourishes the kidney yin and liver blood, while baked licorice tonifies the spleen qi. Thus, Zuogui Yin is considered more tonifying. Both formulas are used extensively today (for example, they are recommended for treating menopausal syndrome), usually with minor modifications.

Tang-kuei Six Yellow Combination (Danggui Liuhuang Tang), contains a mix of raw and cooked rehmannia, with tang-kuei, scute, phellodendron, coptis, and astragalus. It is indicated for fever, night sweating, irritability, red face, red tongue, and dry mouth and lips. Rehmannia and tang-kuei replenish the damaged yin and blood, astragalus helps to suppress excessive sweating due to damaged qi, and scute, coptis, and phellodendron purge the raging fire (they treat infection). Glehnia and Rehmannia Formula (Yi Guan Jian) includes raw rehmannia, lycium fruit, glehnia, ophiopogon, tang-kuei, and melia. This prescription is traditionally indicated for a yin-deficiency syndrome with dry mouth and throat, bitter taste in the mouth, and epigastric pain and fullness. It is today used for a wide range of inflammatory disorders of the digestive system, including hepatitis and gastritis.

Curcuma Powder (Yujin San) is comprised of equal parts raw rehmannia, curcuma, plantago seed, dianthus, talc, and mirabilitum; it is used for treating blood in the urine. Rubia Powder (Qiangen San) is comprised of equal parts raw rehmannia, rubia, gelatin, biota tops, scute, and a half part baked licorice; it is used for uterine bleeding associated with blood heat. Rehmannia and Atractylodes Combination (Gubeng Zhibeng Tang) is made with cooked rehmannia, ginseng, astragalus, atractylodes, tang-kuei and carbonized ginger; it is used for treating of sudden severe bleeding or continuous bleeding associated with qi and blood deficiency.

Two formulas of six ingredients that are direct modifications of Tang-kuei Four Combination are made either by adding persica and carthamus, to yield Persica, Carthamus, and Tang-kuei Combination (Tao Hong Siwu Tang), used to treat the combination of blood deficiency and blood stasis, usually for cases of irregular menstruation, dysmenorrhea, or other menstrual related disorders, or by adding picrorrhiza (a relative of rehmannia that contains some iridoid glycosides) and coptis, to yield Coptis, Picrorrhiza, and Tang-kuei Formula (Siwu Erlian Tang), used to treat blood deficiency manifesting as feverish sensation in the palms and soles, ulceration of the mouth, and night fever/sweating.

One can note from the descriptions of these formulas that the dominant uses of rehmannia have been for treatment of feverish condition, oral ulceration, and bleeding.

SCROPHULARIA IN RELATION TO REHMANNIA

Scrophularia is sometimes used in place of rehmannia in formulas, as occurs with Qinggong Tang (Heart Clearing Decoction), which uses scrophularia with rhino horn, ophiopogon, bamboo leaf, lotus plumule, and forsythia, in a formula that is similar in application to the Rhino and Rehmannia Combination. This formula is given to persons suffering from a feverish disease with depletion of body fluids. Scrophularia is combined with rhino horn, gypsum, anemarrhena, licorice, and oryza, in the formula (Huaban Tang) that is similar in nature to the Rehmannia and Gypsum Combination. This formula is given to persons suffering from high fever with bleeding beneath the skin. Both formulas are said to treat delirium associated with fever.

Although rehmannia is

described in the most ancient texts as treating accumulations and gatherings,

scrophularia is more often selected for that purpose. This is justified, in particular, by the salty taste associated

with scrophularia, which is thought to resolve masses, especially soft masses. An example of a scrophularia-based formula

for masses is Xiaoluo Wan (mass

reducing pill), made with equal parts scrophularia, oyster shell, and

fritillaria.

More often, scrophularia is used along with rehmannia. The formula that epitomizes this combination is Zengye Tang, a prescription of the Wenbing Tiaobian, that has only one additional ingredient: ophiopogon. It is said to clear heat, nourish yin, and moisten the intestines.

Rehmannia with scrophularia occur together in the following larger formulas:

Qingying Tang: used to treat fever, delirium, insomnia, thirst.

Qingwen Baidu Yin: used to treat fever, mania, hemoptysis, restlessness, thirst.

Shen Xi Dan: used to treat high fever, skin eruptions, irritability, red eyes.

Liangying Qingqi Tang: used to treat fever, irritability, swelling in the throat with redness, thirst, shortness of breath, skin rashes.

Jia Wei Dao Chi San: an expansion of Dao Chi San described above, used to treat oral ulceration, fever, poor appetite, and loose stool.

Lianqiao Baidu San, used to treat skin eruptions.

Haicang Dihuang San: used to treat eye disorders, such as keratitis, dry eyes, and aversion to brightness.

Baizi Yangxin Wan: used to treat sleep disturbance with night sweats, heart palpitations, and disorientation.

Baihe Gujin Tang: used to treat hemoptysis, dry and sore throat, hot palms and soles, and night sweats.

Yangyin Qingfei Tang: used for swollen and sore throat, fever, dry nose and lips.

Zengye Chengqi Tang: used for constipation accompanying a feverish disease.

The last three formulations are expansion of Zengye Tang. Compared to formulas that depend on rehmannia without scrophularia, these prescriptions are not indicated for bleeding, but are indicated for hot and dry conditions. It is possible that the high level of iridoids in rehmannia is necessary to provide a hemostatic action.

SUMMARY

Rehmannia, especially cooked rehmannia, is utilized in modern practice as a tonic for the yin and blood and especially to be used in cases of kidney yin deficiency associated with aging. Historically, rehmannia has been used more often for other applications. It has played a key role in formulas for treating heat syndromes that lead to symptoms such as fever (or feverish feeling), sweating (especially night sweating), inflammation (especially of the mouth), bleeding (from all orifices and even under the skin, but especially uterine bleeding), dryness, and thirst. The formulas containing rehmannia frequently included other ingredients for clearing heat, such as forsythia, coptis, gypsum, etc. Many of the symptoms described as indications for these formulas may have been the result of infections and other diseases that are now under better control as the result of modern hygiene and medical interventions. Therefore, rehmannia is now more often being used to treat symptoms that are of somewhat similar nature but of different cause.

A good example of modern use of rehmannia is menopausal syndrome (see: Treatment of menopausal syndrome with Chinese herbs), where hot flushes replace the fever, night sweating is also a problem, dryness of the skin and vagina are common symptoms, and—during the initial phase of menopause—uterine bleeding or irregular menstruation is a characteristic. Clearly, some of the intense fire-purging herbs that we now know also have antibiotic properties and were used in earlier rehmannia formulas are not necessary for such applications. Tonic ingredients in some of the formulas that have been mentioned, such as cornus, tang-kuei, lycium fruit, tortoise shell, anemarrhena, dioscorea, and cuscuta are now often utilized with rehmannia to treat menopausal syndrome.

Tang-kuei Four Combination, as a basic prescription for nourishing blood, has become incorporated into numerous larger formulas that are used in overcoming weakness and fatigue. A good example is the use of Tang-kuei and Ginseng Eight Combination as a general tonic for women (sold as the patent remedy “Women’s Precious Pills”) and the use of Ginseng and Tang-kuei Ten Combination to overcome the adverse effects of Western medical therapies. In the latter case, several therapies produce symptoms of oral ulceration, thirst, feverish feeling, and, when the bone marrow is suppressed to inhibit platelets, spontaneous bruising and bleeding. Clearly, the presence of rehmannia in this relatively large formula could contribute to treatment of those symptoms.

The effects of rehmannia can be explained in relation to the iridoid glycosides, which are currently the only known active ingredients for the dosages of rehmannia that are used (rehmannia also contains some immune-modulating polysaccharides, but the amounts present appear to be small). These iridoids probably function via the adrenal glands to yield changes in the level of anti-inflammatory adrenal hormones and to form a basis for the production of sex hormones (in menopausal women, the adrenal cortex is a significant source of estrogens). The iridoids may also reduce bleeding, stimulate bile production, protect the liver from damage, and reduce elevated blood sugar.

REFERENCES

1. Hsu HY, et al., Oriental Materia Medica: A Concise Guide, 1986 Oriental Healing Arts Institute, Long Beach, CA.

2.

Yang Shouzhong

(translator), The Divine Farmer’s

Materia Medica, 1998 Blue Poppy Press, Boulder, CO.

3. Huang Bingshan and Wang Yuxia, Thousand Formulas and Thousand Herbs of Traditional Chinese Medicine, vol. 2, 1993 Heilongjiang Education Press, Harbin.

4. Bensky D, and Gamble A, Chinese Herbal Medicine: Materia Medica, 1993 rev. ed., Eastland Press, Seattle, WA.

5. Bensky D and Barolet R, Chinese Herbal Medicine: Formulas and Strategies, 1990 rev. ed., Eastland Press, Seattle, WA.

6. Tang W and Eisenbrand G, Chinese Drugs of Plant Origin, 1992 Springer-Verlag, Berlin.

7. Hson-Mou Chang and Paul Pui-Hay But (eds.), Pharmacology and Applications of Chinese Materia Medica, (2 vols.), 1986 World Scientific, Singapore.

8. Hsu HY and Wang SY, The Theory of Feverish Diseases and Its Clinical Applications, 1985 Oriental Healing Arts Institute, Long Beach, CA.

9. Hsu HY and Hsu CS, Commonly Used Chinese Herbal Formulas, Companion Handbook (2nd revised edition), 1990 Oriental Healing Arts Institute, Long Beach, CA.

10. Li Ling, New developments on research on Rehmannia Six Formula, unpublished manuscript, 1996 TCM Information Institute, China Academy of Traditional Chinese Medicine.

11. Cheung CS and Kaw UA, Synopsis of the Pharmacopeia, 1984 American College of Traditional Chinese Medicine, San Francisco.

12. Hsu HY, Present state and perspective of traditional Chinese medicine in Taiwan, Bulletin of the Oriental Healing Arts Institute 1979; 4(6): 5–32.

13. Shen Ziyin, et al., Kidney reinforcement regimen in the treatment of bronchial asthma, Journal of Traditional Chinese Medicine 1982; 2(2): 135–140.

14. Chang IM and Yun HS, Plants with liver-protective activities: pharmacology and toxicology of aucubin, in Chang HM, et al. (editors), Advances in Chinese Medicinal Materials Research, 1985 World Scientific, Singapore, pp. 269–285.

15. Chang HM, et al., Active component from a Chinese composite prescription for the treatment of liver diseases, in Chang HM, et al. (editors), Advances in Chinese Medicinal Materials Research, 1985 World Scientific, Singapore, pp. 221–237.

16. Cheung CS and Tokay H (translators), The six ingredients headed by radix rehmanniae, Journal of the American College of Traditional Chinese Medicine 1982; (2): 55–63.

17. Luo Yanyan, et al., Determination of catalpol in rehmannia root by high performance liquid chromatography, Chinese Pharmaceutical Journal 1994; 29(1): 38–40.

18. Chen Jiayi, Zhang Yuyang, and Wu Qiang, Effect of Jingui Shenqi Pills on sex hormone in aged rats, China Journal of Chinese Materia Medica 1993; 18(10): 619–620.

19. Chen Shuanghou, et al., Pharmacological study of Bushen Shengxue No.1, Chinese Traditional and Herbal Drugs 1990; 21(6): 266–267.

20. Zhang Lili and Shen Ziyin, Effects of kidney yin and kidney yang tonics on animals chronically treated with glucocorticoids, Journal of Traditional Chinese Medicine 1988; (3): 46–49.

21. Unschuld PU, Medicine in China: A History of Pharmaceutics, 1986 University of California Press, Berkeley, CA.

22. Smith FP and Stuart GA, Chinese Medicinal Herbs, 1973 Georgetown Press, San Francisco, CA.

23. Hsu HY, Chen YP, and Hong M, The Chemical Constituents of Oriental Herbs, 1982 Oriental Healing Arts Institute, Long Beach, CA.

24. Recio MC, et al., Structural considerations on the iridoids as anti-inflammatory agents, Planta Medica 1994; 60(3): 232–234.

25. Sionneau P, Pao Zhi, 1995 Blue Poppy Press, Boulder, CO.

Figure 1: Rehmannia glutinosa.

Figure 2: Scrophularia ningpoensis.