Return to ITM Online

WATER CONSUMPTION AND HEALTH

Is 8 fluid ounces, 8 times a day the best advice?

by Subhuti Dharmananda, Ph.D., Director, Institute for Traditional Medicine, Portland, Oregon

When examining the classical medical literature for recommendations on drinking fluids, one encounters a few references to the advantage of drinking warm fluids, and to the potential adverse effects of drinking cold ones, and there are references to the advantage of drinking tea, but there is no mention of drinking fluids in large quantity. In a review of numerous works that include a discussion of rules for keeping healthy, food is extensively described and almost always mentioned in relation to its quantity, consuming beverages is rarely discussed other than in passing. In the English-Chinese Encyclopedia of Practical Traditional Chinese Medicine volume titled Maintaining Your Health (1) some advice collected from traditional works is passed on. Regarding drinking, two ancient books are quoted:

As the book Qianjin Yaofang [Prescriptions Worth a Thousand Gold by Sun Simiao; Tang Dynasty] puts it: those good at health care dine when they feel hungry and drink when thirsty. The book Zunsheng Bajian [Eight Commentaries Honoring Life by Gao Lian; Ming Dynasty] holds the same view that one should not eat until he feels hungry and not drink until very thirsty….

The Encyclopedia points out that in China the traditional beverages were tea and wine, and advice is given regarding how to make the best use of these, indicating their benefits but cautioning about drinking too much of either.

A modernized interpretation of an Ayurvedic recommendation, is this from the Maharishi Institute (2):

Drinking hot water regularly is a classical Ayurvedic recommendation for balancing vata and kapha dosha, strengthening digestive power, and reducing metabolic waste (ama) that may have accumulated. Boil a sufficient amount of unchlorinated tap water or (better still) mineral water in an open saucepan, for at least ten minutes. Keep this water in a thermos flask and take a few sips (or more, if you are thirsty) every half-hour throughout the day. It is the frequency rather than the quantity that is important here. To increase the positive effect you can add 1-2 slices of fresh ginger (or a pinch of ginger powder) to the water when boiling it.

A typical thermos is 1 liter, and there is no suggestion here that the full amount needs to be consumed in the day. In both the Chinese and Ayurvedic cases, the amount of water to consume is not specified, but consumption of fluids appears to be limited, regulated to some extent by actually being thirsty. In China, a practice similar to that of the Ayurvedic recommendation is followed: a thermos of hot water, used to pour over tea leaves, is relied upon to have small amounts of tea throughout the day. According to the Chinese view, it is considered best to have the tea between meals, not while very hungry, and not immediately after the meal (though it can be taken shortly after eating in cases where the meal was too heavy, in an effort to relieve the discomfort and aid the digestion of the food).

In the Quintessence Tantras of Tibetan Medicine (3) it is noted that there are three main beverages: milk, which opposes wind and increases phlegm; water which opposes bile and increases wind; and alcohol which opposes phlegm and increases bile. This description follows the Ayurvedic tridosha system (wind = vata or vayu; phlegm = kapha; bile = pitta). In Tibet, where there are vast areas without easy access to water, different natural water sources are recognized as having different benefits (or harm) for drinking:

The different types of water include rainwater, melted snow, river water, spring water, well water, lake water, and forest water. Rainwater is of supreme quality and the rest are successively inferior. Rain water is of indeterminate but pleasant taste, is invigorating and satisfying, has cool, light power, and is like nectar. Melted snow water comes in rushing torrents. It is very fine, cool water which is hard for the digestive power to withstand. Still calm areas of water [such as the lake and forest water] produce germs, elephantiasis, and heart diseases. Good water is that which comes from a clean area and which has felt the touch of the sun and wind….Cool water cures fainting, fatigue, hangovers, vertigo, vomiting, thirst, obesity, blood and bile disorders, and poisoning. Freshly boiled water increases digestive heat, facilitates digestion, cures hiccoughs, promptly cures distention of the abdomen, caused by phlegm, and cures asthmatic conditions, fresh colds, and infectious fevers. Cool boiled water does not increase phlegm and cures bile conditions, but if it is left standing for one day or more it acquires toxic properties and increases all three humors.

Consistent with certain ancient Ayurvedic suggestions, which differ from the modern one, the drinking of beverages is usually associated with meals and its quantity related to the amount of food consumed. The description in the Tibet tantras is: "One should fill two parts of the stomach with food, one with drink, and in the fourth part leave room for the fire-like equalizing wind, the decomposing phlegm, and the digestive bile." Of course, it is difficult to know what would constitute one-fourth part of the stomach, but the idea expressed here is to not eat until full, indeed, only half full, and then consume far less beverage than food, still not filling the stomach. Depending on the kind of food consumed and the type of humoral imbalance a person might have, different beverages would be recommended, which might best be taken at different times after completing the meal. At any rate, the quantity of the beverage to be consumed is not as critical as the type of beverage, and it is limited.

Some traditional health specialists caution about drinking too much water (or other beverages) with a meal, concerned both that digestive juices will be overly diluted and that the stomach will be overly filled, causing one to feel uncomfortable and tired. In his book Ayurveda: Life, Health, and Longevity (4), Robert Svoboda comments:

Water is essential for life, but too much water ruins health. The substances found in a humid climate tend to be full of humidity themselves, and so are "heavy" for digestion; they contribute too much water to the system, making it difficult for the digestive fire to remain hot enough to function efficiently.

Large parts of India have a humid climate, which is a basis for this wording. However, the concern is for foods that have a moist nature, wherever they might be grown, as well as pointing to the problem of consuming too much moisture through beverages. A similar concern is raised by Chinese physicians, who note that the "spleen" system is easily harmed by too much moisture, and then digestion is adversely affected, so eating too many foods that are full of moisture, or drinking a lot of fluids, would be considered potentially harmful.

By contrast, within the past few years, especially in America, millions of people have adopted the practice of carrying water bottles (often with expensive pre-bottled water) wherever they go. While these are often taken along when exercising (even if not vigorous or prolonged), water is also consumed copiously during sedentary periods. At modern offices, many workers go to the water coolers, not just to take a break but to fill up on the publicized daily water quotient, sometimes carting large mugs back to their desks. The bottled water industry reaps the benefits, with 4 billion dollars a year annual sales (in the U.S. alone) and growing. Where does this intensive drinking behavior come from?

Most people today can cite the 8 x 8 rule: drink at least eight ounces of water, 8 times a day: that is two quarts. Two quarts of total fluid isn't very much in a day, but sometimes another rule is imposed: caffeinated and alcoholic beverages don't count; some say nothing but water counts in reaching this total. Is this quantity of water really necessary? Is it advantageous? Is it really true that coffee and tea don't count? Did the Chinese, many of whom only drank tea but not water, shrivel up and die because the caffeine drained out all their fluids?

A few years ago, Heinz Valtin looked into the origin of the 8 x 8 rule and searched for evidence for it (4). He noted that (emphasis has been added):

No scientific studies were found in support of 8 × 8. Rather, surveys of food and fluid intake on thousands of adults of both genders, analyses of which have been published in peer-reviewed journals, strongly suggest that such large amounts are not needed because the surveyed persons were presumably healthy and certainly not overtly ill. This conclusion is supported by published studies showing that caffeinated drinks (and, to a lesser extent, mild alcoholic beverages like beer in moderation) may indeed be counted toward the daily total, as well as by the large body of published experiments that attest to the precision and effectiveness of the osmoregulatory system for maintaining water balance. It is to be emphasized that the conclusion is limited to healthy adults in a temperate climate leading a largely sedentary existence, precisely the population and conditions that the "at least" in 8 × 8 refers to. Equally to be emphasized, lest the message of this review be misconstrued, is the fact (based on published evidence) that large intakes of fluid, equal to and greater than 8 × 8, are advisable for the treatment or prevention of some diseases and certainly are called for under special circumstances, such as vigorous work and exercise, especially in hot climates.

He presented some examples of the lengths people will go to in order to get their water quota:

A colleague has told me he estimates that something like 75% of his students carry bottles of water and sip from them as they attend lectures; indeed, a pamphlet distributed at the University of California Los Angeles counsels its students to "carry a water bottle with you. Drink often while sitting in class...."

His search for the origin of the 8 x 8 rule turned up nothing concrete, possibly an off-hand statement from a nutritionist (who had commented on drinking at least 6 glasses a day), and no scientific basis or detailed analysis seems to be at its source. One possible origin point was this comment from a 1945 report by the Food and Nutrition Board of the National Research Council:

A suitable allowance of water for adults is 2.5 liters daily in most instances. An ordinary standard for diverse persons is 1 milliliter for each calorie of food. Most of this quantity is contained in prepared foods.

If one ignores the last rather important comment, that most of this quantity of water is in foods, you may get the impression that the Council intended that you need to drink 2.5 liters of water (the 8 x 8 rule leads to consuming 1.9 liters). At present, 50 years later, when all health authorities emphasize the need to consume plenty of fresh fruits and vegetables, which are comprised mostly of water, it is easy to get the 2.5 liters per day without drinking copious amounts of water. Further, with advisories that sedentary women consume only about 2,000 calories per day, the suggested 1 ml/calorie translates to only 2.0 liters total water needed (again, mostly from foods); adding 1.9 liters of water through drinking glass after glass of it would simply double the recommended intake.

There are some obvious cases where higher fluid consumption would be important, such as for people who are perspiring profusely (due to exercise or hot weather or both, or even as the result of a feverish disease), those who are losing fluids due to diarrhea, and those who tend to form kidney stones.

DIURETIC DRINK MYTHS

The idea that drinking beverages containing natural diuretic substances, such as caffeine, actually drain fluid out of the body (i.e., creates a net loss in body water content) is simply a misunderstanding of the diuretic action. Mild diuretics found in ordinary foods and beverages may slightly hasten the removal of water from the body, but the mechanisms (osmogregulatory system) that maintain proper body balance of water, electrolytes, and other components prevent excreting more water than is taken in from all sources. The exception would be where there has been an unhealthy water build-up (edema): one could lose some of the excess without coming up against the natural barriers to dehydration. But for most people, drinking naturally caffeinated tea all day is not different than drinking water all day in terms of water balance, and this is the historical experience in China where drinking plain water was not a routine practice. People who avoid natural diuretic substances (such as caffeine) over an extended period of time may experience a water loss upon encountering these diuretics for the first day. The water balance will be restored again almost immediately with continued ingestion of the mild diuretics or with return to avoidance of them. While the original concerns about drinking beverages other than water were not based on actual data, more recent studies following up on this issue have been conducted to evaluate the potential role of natural diuretics, and, as Valtin relays, they show no significant effects (5). In a recent study, AC Grandjean and his colleagues observed the effects of different beverages on body hydration (6), in the discussion, they noted:

The purpose of this study was to measure, in healthy, sedentary individuals, the effect on hydration of two regimens, one that included drinking water as part of the dietary beverages and one that did not….In summary, the results herein are preliminary, but suggest that inclusion of plain drinking water compared to exclusion of plain drinking water in the diet for three days did not affect the measures of hydration used in this study.

PROBLEMS WITH DRINKING TOO MUCH?

Thus far, no health problems have been blamed on drinking too much water, at least, within the range recommended in the 8 x 8 rule. Some people may be draining their pocketbook by following this rule using fancy bottled waters, perhaps preventing investment in other, more beneficial, health practices. Other people may worry that they are not getting enough fluids when they curtail their water consumption in order to deal with "overactive bladder," a condition that is rapidly increasing in frequency of occurrence (it has been claimed that it affects 33 million Americans!). Some people, being cautioned not to drink anything other than water, may miss out on the benefits of the other beverages, such as high flavonoid and antioxidant content of fruit juices, tea, coffee, beer, and hot chocolate, or the protein and calcium in milk. Thus, the problem with the advice to drink copious amounts of water and avoid other beverages might be secondary and unanticipated effects of the advice.

Returning to the traditional advice, one might inquire why the suggestion is to only drink when thirsty (as per the Chinese system) or why drink a few sips regularly throughout the day (as per the Ayurvedic suggestion)? The Chinese proposal follows up on the Daoist concept that to live a healthy and long life one must do things in moderation and pay attention to nature and to the body signals. Thus, eating when hungry and drinking when thirsty, with only enough food and drink to satisfy actual needs for one's activities, fits that concept; consuming more that what is essential is seen as a defiance of nature. For the Ayurvedic suggestion of drinking warm water frequently (depending on the dosha imbalance, this could be room temperature water to quell fire, warmed water to disperse phlegm, or hot water to calm wind), the practice is seen as a mild stimulus to the digestive system to promote the elimination of wastes. Because of the strong reliance in this healing system on the idea of preventing accumulation of wastes, frequency of promoting elimination is considered important. When consuming the water, the amount of water is not the key to this approach, rather it is taking enough water to have an effect (which is just a few sips). If an ounce of fluid were consumed each time, every half hour for all waking hours (about 16 hours), that would amount to half the fluid volume of the 8 x 8 rule. Though many modern Ayurvedic commentators combine the 8 x 8 rule with the teaching about drinking warm water frequently, no traditional documents reflect that approach.

In the encyclopedia volume Maintaining Your Health, a concern is briefly mentioned about excessive tea drinking in relation to ingestion of its water component in too large a quantity, commenting that this can cause "overhydration, increase the burden on both the heart and kidney owing to the increase amount of water in the body, and effect the deficiency of vitamin B as well." High water intake may increase blood pressure temporarily (potent diuretics are used to counter hypertension); it remains unclear whether the high volume of water actually puts a strain on the kidneys. The B-vitamin issue is related to its water solubility and the fact that it can be flushed from the body with urination. However, the main concern expressed for drinking too much tea has to do with the pharmacological actions of the tea components, rather than the water.

SUMMARY

It is not the purpose of this article to suggest that people should cut back on their water consumption or should cease drinking water in favor of other beverages. However, one purpose of presenting this information is to challenge the advice that may be too freely given without understanding its origins and the potential to contradict other advice that may be even better. One of the current popular themes is to consume copious amounts of water and to avoid other beverages, particularly those which are perceived as having a potential diuretic effect. Many people may not need so much fluid consumption; some may do better with less, and some people may gain an advantage from drinking beverages aside from water, including those that contain modest amounts of caffeine. For example, risk of certain diseases, including cardiovascular disorders and cancer, are thought to decline with high intake of flavonoids; the primary flavonoid sources for most people are not foods, but beverages other than plain water, such as tea, wine, beer, and fruit juices. Therefore, it would be more appropriate to consider a wider range of individual requirements for health before taking the recommendations that have been heavily promoted by the bottled water industry. Certainly, for practitioners of traditional medicine who might wish to relay the long held traditions of Chinese, Ayurvedic, or Tibetan medicine, drinking large amounts of water does not appear to be consistent with the age old advice regarding health maintenance.

REFERENCES

- Xu Xiangcai (chief editor), The English-Chinese Encyclopedia of Practical Traditional Chinese Medicine, (volume 9, Maintaining Your Health) 1989 Higher Education Press, Beijing.

- Maharishi Ayurveda: http://www.tmscotland.org/mav/tips.html

- Clark B (translator), The Quintessence Tantras of Tibetan Medicine, 1995 Snow Lion Publications, Ithica, New York.

- Svoboda R, Ayurveda: Life, Health, and Longevity, 1992 Penguin Books, India, New Delhi.

- Valtin H, "Drink at least eight glasses of water a day." Really? Is there scientific evidence for "8 × 8"?, American Journal of Physiology-Regulatory Integrative and Comparative Physiology 2002; 283(5) 993-1004.

- Grandjean AC, et al., The effect of caffeinated, non-caffeinated, caloric and non-caloric beverages on hydration, Journal of the American College of Nutrition 2000; 19(5): 591-600.

- Grandjean AC, et al., The effect on hydration of two diets, one with and one without plain water, Journal of the American College of Nutrition 2003; 22(2): 165-173.

May 2005

Classic Oriental Style:

small cups for sipping small quantities of tea.

|

Modern Western Style:

large mugs for gulping big quantities of fluid.

|

Mostly Water. Eating the suggested five servings of fruit in

a day provides large amounts of water.

Many fruits are more than 80% water.

|

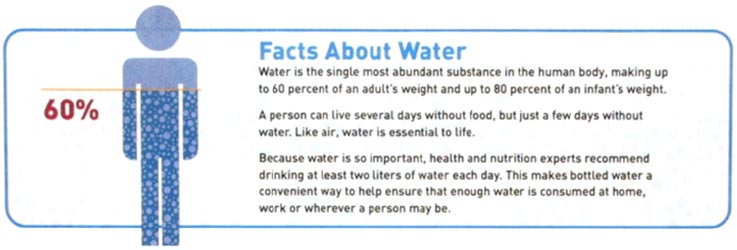

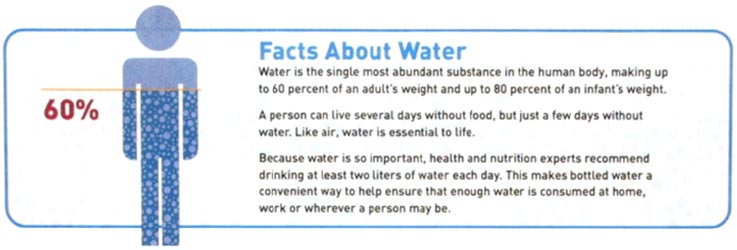

Promo for Drinking Bottled Water. The text reads:

"Because water is so important, health and nutrition experts recommend

drinking at least two liters of water each day. This makes bottled water

a convenient way to assure that enough water is consumed at home, work,

or wherever a person may be."

|