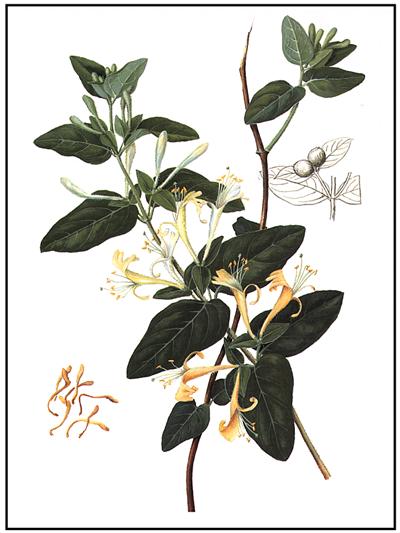

Figure 1: Lonicera japonica.

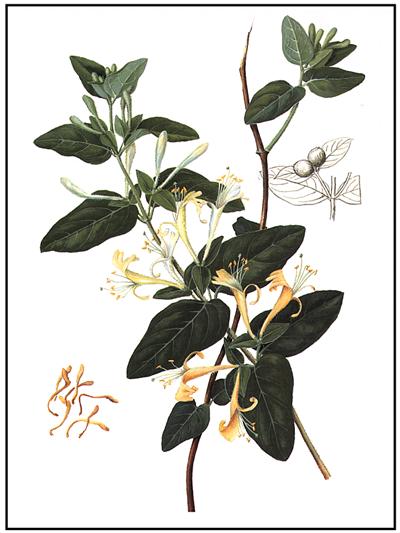

Figure 2:Forsythia suspensa.

YIN QIAO JIE DU PIAN

A patent remedy based on Yin Qiao San

Yin Qiao Jie Du Pian is a famous patent remedy of China used mainly in the treatment of acute respiratory system ailments, such as influenza and common cold. It is based on the traditional formula Yin Qiao San: yin refers to lonicera (jinyinhua); qiao refers to forsythia (lianqiao); san means powder, whereas pian means tablet (literally: a slice). Thus, the formula name identifies the two key ingredients (see Figures 1 and 2) and the form of administration (traditionally, a powder is decocted for a short period of time, just a few minutes). In addition to tablets, Chinese factories produce the formula in pills (wan) and extract granules that produce a tea by adding boiled water.

In the name of the modern patent remedy, the formula's function is also defined: jie du means to remove (jie = remove by dispersing) toxins (du), where toxin is a broad concept that encompasses, as a modern interpretation, viruses. Other types of toxin would be poisons associated with insect and snake bites, bacteria that cause skin abscesses, and changes in cells that lead to their abnormal growth or metabolism, as occurs in tumors. In most cases, toxins yield swellings, especially those that are reddened and/or that feel warm to the touch. Translations of the patent remedy name may refer to "antiphlogistic" action as an interpretation for jiedu; that is, it reduces inflammation or fever.

Yin Qiao San was first recorded in the Wenbing Tiaobian (Detailed Analysis of Epidemic Febrile Diseases; 1798 A.D.) by Wu Tang (1758-1836). This book was one of several similar publications that appeared at this time in Chinese medical history (during the latter part of Ming Dynasty and throughout most of the Qing Dynasty), involving more than two centuries of intensive work on epidemic diseases. These diseases were called "warm" diseases (wen = warm; bing = disease), which were understood to come in waves, being passed on from person to person, causing fever as a characteristic symptom. Other well-known books on the same subject included the Wenyi Lun (Treatise on Acute Epidemic Febrile Diseases; 1642 A.D.), Wenre Lun (Treatise on Epidemic Fevers; 1746 A.D.), and Wenre Jingwei (An Outline of Epidemic Febrile Diseases; 1852 A.D.).

Although epidemic diseases had been dealt with before, most notably in the Shanghan Lun, there were two new concepts that these books promulgated. First, it was recognized that there were transmissible agents involved in the epidemics, not just climate-related factors; second, it was recognized that the transmissible agents of concern involved heat-type influences, as opposed to the cold influence that was described in the Shanghan Lun and that had also been emphasized in the Huangdi Neijing. It is likely that the primary diseases of this time period-when the theory of warm diseases evolved-were different from those at the time of the Shanghan Lun (Han Dynasty, over a thousand years earlier).

According to History and Development of Traditional Chinese Medicine (1): "In the Ming and Qing, infectious diseases were often widespread, causing serious harm. According to incomplete statistics, these epidemics occurred 64 times in the 276 years of the Ming and 74 times in the 266 years of the Qing." The epidemics, as viewed from the present, were suggested to have resulted from adverse conditions brought about by "constant famine due to crop failures, and chaos caused by war." Wu Youke, author of Wenyi Lun, saw many persons dying of the epidemics and complained that the diseases were being treated by mistaken principles, namely, by treating them as if they were caused solely by exogenous (climate-related) factors. In the introduction to his book, Wu stated that "Epidemic febrile disease is a kind of disease not caused by wind, cold, summer heat, or damp, but by a kind of strange factor [yiqi; alternative influence] between earth and heaven." He also called the cause of these diseases zaqi (unusual influence) and liqi (epidemic pathological influence). Wu Tang, who developed Yin Qiao San, began his study of medicine with the Wenyi Lun.

The theoretical developments of Warm Disease Theory were considered important because most physicians had adopted the Shanghan Lun as their primary guide to understanding prescription of herbs and had been enamored with prescribing warm herbs. Xu Dachun (1693-1771) was strong critic of medical practices during this time who supported the study of classics but disliked the way their knowledge was being applied; he frequently complained about the adverse consequences of too much reliance on warming herbs (2).

The traditional Chinese books on warm epidemic diseases have inspired English language works about the disease descriptions, diagnostic categories, therapeutics, and specific formulas recommended in them. The first book that appeared on this subject in English was The Theory of Feverish Diseases and Its Clinical Applications, published by the Oriental Healing Arts Institute in 1985 (3). In 2000, a Chinese language text, originally published in 1979 and used in TCM colleges in China, was translated for Paradigm Publications with the simple title Warm Disease Theory (4).

Yin Qiao San is included in these texts and also presented in all Chinese herb formula books. The formula was originally prepared as a powder. The translation of dosages has varied from text to text. As an example of instruction for preparation of the formula, here is the information provided in Warm Disease Theory:

| Lonicera | 10 g |

| Forsythia | 10 g |

| Platycodon | 6 g |

| Arctium | 10 g |

| Mentha | 10 g |

| Soja | 10 g |

| Schizonepeta | 12 g |

| Lophatherum | 10 g |

| Licorice | 6 g |

"Grind all medicinals into powder. Divide them into 6 gram doses and boil them with fresh phragmites. As soon as the decoction starts giving off an aroma, administer it quickly." It is cautioned that the herbs should not be boiled too long, as their flavor will become thick and will then fail to float (remain light) so as to be able to treat the lung, instead sinking and entering the middle burner. Further, it is explained in this text that: "if the disease is severe, administer the medicinals every four hours, up to three times during the day and once at night. If the disease is mild, give every six hours, twice during the day and once at night. If the disease lingers, continue prescribing the medication."

The formula is considered to have an acrid and cooling nature that will disperse and dislodge warm pathogens from the body surface (in the muscle exterior, where one experiences aching of the muscles as part of the symptom complex). As to the role of individual herbs of the formula, the book Warm Disease Theory presents this rendition:

Yin Qiao San as the representative acrid-cool preparation within the context of Warm Disease Theory. In fact, the author of the formula named it after two heat-clearing anti-toxin herbs, rather than the acrid-cool ingredients, so as to focus attention on its treatment of the warm pathogen.

The Advanced Textbook of Traditional Chinese Medicine and Pharmacology (5) explains the action of the formula this way:

At the onset of seasonal febrile diseases, the pathogens only affect weifen [the defensive portion], where they [come into conflict] with the antipathogenic qi [weiqi], giving rise to fever, mild chills, and headache. When wind-heat affects the throat, lung qi is inhibited and cough and sore throat occur. When wind-heat damages body fluid, thirst appears. The therapeutic principle at this stage should be to expel the pathogens from the exterior and purge heat and toxins. In this prescription, the chief ingredients are lonicera and forsythia, which are effective for purging heat and toxins, releasing stagnant lung qi, and expelling pathogens at the surface; mentha, schizonepeta, and soja are adjuvant ingredients, helping to expel the pathogens from the exterior. Schizonepeta, which is warm, and combined [in this formula] with acrid and cold drugs, can enhance the prescription's action to expel the pathogens from the exterior. Used together, platycodon, arctium, and licorice can release inhibited lung qi, dissipate phlegm, and cure sore throat; lophatherum and phragmites serve as the assistant drugs, purge heat and promote the production of fluid. Licorice is a guide drug to balance the effects of the other drugs.

The symptom pattern calling for this type of treatment, and for this formula specifically, is that attributed to any epidemic pathogen of warm nature attacking the lung's defensive qi (but not harming the organ's other functions). The resulting symptoms are: fever, mild aversion to wind, sore throat, headache, scant sweating or absence of sweating, coughing, oppression or pain in the chest, mild thirst, thin white or thin yellow tongue moss, red tongue tip, and floating rapid pulse. Some, though not all of these symptoms, fit the characteristics of the viral disease influenza, explaining the modern emphasis on use of the formula for that purpose. Influenza characteristically produces symptoms of fever (often with chills), aches and pains (particularly affecting the back), headache, scratchy sore throat, and cough (non-productive, unless a secondary bacterial infection develops).

The symptom pattern depicted above is different than that associated with the picornaviruses (mainly rhinoviruses) which produce the common cold. Influenza may manifest symptoms similar to the common cold, especially upon reinfection by the same virus (the first infection prepares the immune system, so that the second infection produces more limited symptoms). Symptoms of the common cold include a burning sensation in the nose or throat (pharyngitis often develops), followed by sneezing, nasal discharge, and malaise. Fever is usually not present. The lungs are usually not involved in the disease, unless a secondary bacterial infection develops. Despite the somewhat different pattern compared to that indicated for the formula, Yin Qiao San and its modern patent versions have been applied to treating the common cold, partly because it has been recognized as generally effective rather than specifically effective for pathogens influencing the respiratory system and, more broadly, as effective for a wide range of acute viral infections. Still, it is theoretically most appropriate for treating influenza.

It is common for Chinese doctors to speak of wind-cold and wind-heat ailments in relation to upper respiratory diseases, with translation of the condition, in either case, as the "common cold." The Chinese term for this category of disease is ganmao, and is interchangeably translated as common cold or influenza (gan = to feel; mao = oozing). In the Advanced Textbook of Traditional Chinese Medicine and Pharmacology (5) it is said that: "Generally, influenza falls into the category of the common cold caused by wind-heat," this explanation illustrates the free intermixing of the modern medical terms for different viral infections during translation. In the book Practical Therapeutics of Traditional Chinese Medicine (15), the chapter titled "Common Cold" provides this explanation: "If during a certain period, many cases [of ganmao] are observed over a large area and the symptoms are very similar, then [the disease] is known as shixing ganmao (epidemic cold), or, in Western medicine, as flu." Thus, influenza is understood to be a wind-heat ailment that appears as epidemics.

Dr. Chen Changsheng presented his views on the treatment of common cold at the Fifth Annual Meeting of the Oriental Healing Arts Institute (6), where he differentiated "colds due to wind-cold" (having chills, fever, sneezing, coughing, headache, generalized aching, and occasionally stiffness of the neck) from "colds due to wind-heat" (having higher fever, less chills, headache, sore throat, and coughing). He recommended Mahuang Tang (Ma-huang Combination) for the former, which corresponds to the common cold (except for fever), and Yin Qiao San (Lonicera and Forsythia Formula) for the latter, which corresponds to influenza. As to Yin Qiao San, he commented further that: "This is an old formula, but one that is still a favorite with patients and doctors alike. Today, it is available in herbal shops in the more convenient form of tablets and capsules, although the exact dosage must still be prescribed by the patient's doctor."

The modern Yin Qiao Jie Du Pian is made according to a complex procedure that involves blending herb powders, decocted herbs, and distilled essential oils (see: The history and modern development of Chinese patents, for the full text description as appears in the Chinese Pharmacopoeia). Unlike the original Yin Qiao San, this tablet (or pill) preparation is unlikely to induce perspiration, since it is not prepared as a hot tea. It is a common situation that formulas originally used for sweating therapies are now presented in forms that do not rely on diaphoretic action, but still carry with them the same indications (see: On the importance of perspiration in Chinese medical diagnosis and therapy).

Modern pharmacology investigations reveal that the herb formula helps inhibit viruses and may promote immune attack against pathogens, thus making it a therapy that is particularly useful for the earliest stage of the disease, when the level of virus and the symptomatic response is still minimal. According to Chinese Herbal Medicine: Formulas and Strategies (7), possible applications of Yin Qiao San classified by modern disease categories include: upper respiratory tract infections, influenza, acute bronchitis, measles, epidemic parotitis, acute endometritis, and early stage encephalitis or meningitis. Chinese-English Manual of Commonly Used Prescriptions in Traditional Chinese Medicine (8) adds to this list: acute tonsillitis, mumps, and acute supperative infection (e.g., initial stage of skin eruptions). However, as the main use, this text specifies that: "The therapeutic principle of this prescription is reasonable, the concept of compatibility [of the herbs within the formulation] is strict, and its curative effect is fruitful, and has become a typical recipe for common cold of the wind-heat type."

The modern Chinese understanding of the formula's action is presented in 100 Famous and Effective Prescriptions of Ancient and Modern Times (9), citing a report in the 1986 Journal of Traditional Chinese Medicine:

This recipe has a rather strong antipyretic, anti-inflammatory, and anti-anaphylactic [anti-allergy] action. The pharmacological characteristic of this recipe, besides the anti-inflammatory and anti-anaphylactic actions, lies in the fact that it can strengthen the phagocytic ability of the macrophages in the inflammatory sites. This characteristic suggests that the influence of this recipe to the immunological system is different from that of the commonly used steroidal and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory and antiallergic agents (both of them will inhibit the body's anti-infection immunology at the time when they shown their anti-inflammatory and antiallergic actions). Furthermore, it is found through the comparison among Yin Qiao San's bags [granule packets], tablets, and decoction that the Yin Qiao San bags have the strongest antipyretic, anti-inflammatory, and anti-anaphylactic action. The content of the volatile oil and nonvolatile oil in Yin Qiao San bags is obviously higher than those in the same amount of Yin Qiao San's tablets and decoctions.

The book also relays the results of a study of Yin Qiao San on the effect of the treatment for upper respiratory tract infections, quoting from a 1986 report in the journal Research on Chinese Patent Medicines:

Yin Qiao San bags were used to treat 25 cases of infection of the upper respiratory tract. As a result, the average fever abatement time was between 8 and 72 hours, with an average of 35 hours. The total effective rate was 90.2%. In the treatment, 2-4 bags of Yin Qiao San were put into a Thermos cup or a cup with a cover and soaked in boiled water for 3-5 minutes before the intake. The drug should be taken 3 times a day.

Pharmacology and Applications of Chinese Materia Medica (10) notes for Yin Qiao San that "better results are obtained in febrile diseases [as opposed to those without fever] or at the early stages of common cold [ganmao]." In the book Traditional Chinese Treatment for Infectious Diseases (11), the authors comment that: "It is difficult to evaluate a therapy for the treatment of a self-limited disease like common cold. However, controlled studies have shown that traditional therapy shortened the course of the disease and relieved the symptoms quickly. It relieves symptoms without side effects when administered properly." With regard to Yin Qiao San: the formula is indicated specifically for wind-heat syndrome, it should be taken warm, and the patient should be "kept warm with dry clothes in order to avoid any relapse." When using the tablets or pills, one should take them with warm water or consume warm tea to substitute for some of the missing effects of taking a warm decoction of the herbs.

According to patent medicine books (published in the U.S. during the 1980's) that reported on imported products (12, 13, 14), Yin Qiao Jie Du Pian made available in the U.S. initially came from two factories: one in Tianjin (Tianjin Drug Manufactory) and one in Beijing (Beijing Tong Ren Tang). The authors of these books cautioned about one product that was imported from Tianjin, depicted on its label as a "superior" version, contains drugs: paracetamol, and chlorpheniramin (these drugs are listed on the product label, which was usually not consulted by those who purchased the products in the U.S.; the "superior" product is in the form of coated tablets). Patent medicine manufacturers have explained that the inclusion of the drugs in the traditional herb products makes the new product work more strongly and quickly, but the herbs assure a more complete curative effect and prevent side effects of the drugs. The standard Tianjin product and the Tong Ren Tang versions do not contain drugs and are still being imported. In addition, other factories have introduced their own versions of Yin Qiao Jie Du Pian based on the good reputation that has developed for the effectiveness of the formula. Yin Qiao San has been available in the U.S. since 1976 as a dried extract (fine granules) from Taiwan-based companies. The dried extracts may be consumed as teas, and also are encapsulated. Several Western manufacturers of Chinese herb formulas have made modified versions of Yin Qiao Jie Du Pian, though without the complex manufacturing procedures that are used at the large Chinese factories.

In sum, Yin Qiao San and Yin Qiao Jie Du Pian (or other prepared forms based on Yin Qiao San) are highly respected remedies for wind-heat ailments, mainly influenza, caused by infectious agents. The formulas are also given for treatment of several viral infections, other than influenza, and some bacterial infections, usually in the early stage. The herbs are administered three to four times per day until the symptoms of the ailment has subsided, usually within two days after initiating therapy for upper respiratory infections. The use of the formula is not associated with any side effects.