ZUSANLI (STOMACH-36)

Zusanli is one of the most frequently used of all acupuncture points and is certainly the most intensively studied single point treatment in acumoxa therapy. The indications for use of this acupuncture point are many, and the claimed benefits are substantial. Many proposals for acupuncture research in the West rely upon complex treatment protocols involving several acupuncture points; single-point acupuncture research to confirm Chinese reports is rare. If one wishes to demonstrate that acupuncture is therapeutically beneficial, and to do so with a simple treatment that is easily reproduced, needling zusanli seems most appropriate. While many acupuncturists would prefer, on the basis of their training, to administer a more complex treatment, few can deny that the proclaimed benefits of treating this point, even alone, are worthy of investigation.

HISTORICAL BACKGROUND

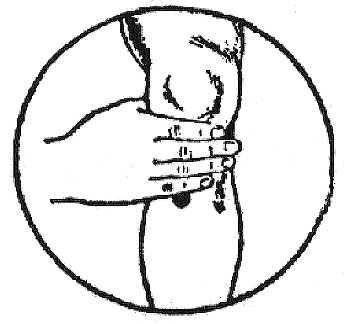

Zusanli is one of the 365 classical acupuncture points, located on the leg portion of the stomach meridian (see Figure 1). According to the analysis presented in Grasping the Wind (1) the point has had several names attributed to it, though most of them include the term sanli. In fact, in traditional acupuncture texts, such as the Internal Classic (Nei Jing, ca. 100 B.C.) and the Systematic Classic of Acupuncture (Jia Yi Jing, 1601 A.D.), the point is usually referred to simply as sanli. Most authors agree that, as described in Essential Questions (Nan Jing, ca. 100 A.D.), sanli refers to the method for locating the point on the leg: it is three cun (about three inches, or about 4 finger widths; see Figure 2) below the knee. More specifically, it is 3 cun below the Stomach-35 point, dubi, parallel to the bottom of the knee cap. Although the term li is a standard Chinese distance measurement that normally corresponds to about one-third mile, the term sanli is a grander one, more fitting the naming system used for acupuncture points, than sancun. It has been suggested that li might also have been selected because it sounds the same as the related character li meaning to rectify or regulate; for example, sanli could secondarily imply regulating the three burners.

Zu refers to foot, indicating that the point is on the portion of the meridian that runs to the foot: the stomach meridian is often referred to as the foot yangming meridian. In fact, there is another acupuncture point, shousanli (Large Intestine-10) which is located 3 cun below the prominent bone of the elbow; shou refers to hand, indicating that the point is on the hand yangming meridian, the large intestine meridian that runs from the hand along the arm.

One other name for zusanli that is of particular significance is xiaqihai, meaning lower sea of qi. The upper sea of qi, simply called qihai (Conception Vessel-6), is located at the dantian (which is below the navel about 1.5 inches). The dantian is thought to be the primary reservoir of the body’s qi, at least according to the Taoist tradition. One of the key Taoist breathing exercises involves abdominal breathing with visualization of air, a type of qi, being drawn to this spot (“breathing into the dantian”). In the Ling Shu (2) it is said that “the center of breathing is the sea of qi.” Thus, the term xiaqihai implies that needling this point may have an effect comparable to needling qihai.

In the Nei Jing Su Wen (3), the bilateral zusanli points are mentioned as two of the eight points for eliminating heat from the stomach. Zusanli is also mentioned as a treatment for knee pain that “feels so severe that the tibia feels broken.” Zusanli is described as a he point (confluence point) of the stomach meridian. He points are where the qi submerges in its flow along the meridian; it submerges into the vast interior ocean of qi and blood. According to Essential Questions, confluent points are indicated for treating diarrhea caused by unhealthy qi. The Ling Shu mentions that confluent points are indicated for disorders in the fu organs (the stomach is one of the fu organs). The Systematic Classic of Acupuncture (19) includes these indications for zusanli:

For cold in the intestines with distention and fullness, frequent belching, aversion to the smell of food, insufficiency of the stomach qi, rumbling of the intestines, pain in the abdomen, diarrhea of untransformed food in the stools, and distention in the region below the hearts, sanli is the ruling point.

In a collection of odes to acupuncture (20), also obtained from the Systematic Classic of Acupuncture, the following statements about zusanli are made:

· Acute diarrhea and vomiting, search out yingu (Kidney-10) and sanli (Stomach-36).

· Who knows in a weakening cough to search instantly for sanli?

· A sound like cicadas in the ear which you want to diminish, be certain to keep in store the point sanli below the knee.

· A little boy with indigestion, sanli is noblest.

· If perhaps the bladder does not disperse water, then again it is suitable to seek within sanli.

· If there is dizziness as you plunge the needle in [while performing acupuncture], immediately reinforce zusanli or reinforce renzhong (Governing Vessel-26).

· If the mind is perturbed and anxious, pierce sanli.

· Sanli removes great debility arising from malnutrition—Hua Tuo mentioned this.

· Cold and numbness when the kidney qi is shriveling—select the earth point of foot yangming [zusanli]

· Heal a breath blocked above with zusanli.

A more lengthy discourse on the value of this point is included (20) in “Ma Danyang’s song on the twelve points shining bright as the starry sky and able to heal all the many diseases”:

Sanli under the eye of the knee, three cun, in between the two tendons, one can reach into the center of a swollen belly, it is splendid at healing a cold stomach, intestinal noises, and diarrhea, a swollen leg, sore knee, or calf; an injury from cold, weakness or emaciation, and parasitic infection of all sorts; when your age has passed thirty, needle and moxa at this point; change your thinking to find it, look extremely carefully; three cones of moxa, eight fen in, and peace.

There are also references in the book to using zusanli along with other points to treat beriberi (this medical term refers to swelling of the legs that is due to vitamin B1 deficiency, a common problem in the Orient; obviously, the original statement did not specify the cause of the leg swelling). In addition, there is an explanation of why needling zusanli during pregnancy is contraindicated, except at the time of delivery:

At one time in the past, the Song Dynasty Crown Prince loved the medical arts. He was out wandering in his park when he came across someone looking after a pregnant woman. The Crown Prince made a diagnosis on her and said: “The baby is a girl.” He ordered the physician Xu Wenbai to make a diagnosis; Wenbai replied: “There are twins, a boy and a girl.” The Crown Prince was furious and wanted to cut the woman’s belly open to find out. Wenbai stopped him, saying: “please may I use my humble needles?” The he drained zusanli, and reinforced hegu (Large Intestine-4), and the fetuses responded to his needle and fell. And it turned out to be as Wenbai had predicted. Therefore, it is now said one should not needle these points on pregnant women.

MODERN INDICATIONS

The current standard indications for zusanli, as reviewed in Advanced Textbook of Traditional Chinese Medicine and Pharmacology (21) are: stomach ache, abdominal distention, vomiting, diarrhea, dysentery, indigestion, appendicitis, flaccidity and numbness of the lower limbs, edema, mastitis, mania, epilepsy, cough, vertigo, palpitation, and emaciation due to consumptive disease. This latter indication corresponds to the concept that needling this point can tonify the sea of qi and thereby help to stop the wasting disease and restore ones body weight and vitality.

To illustrate the uniformity of indications amongst the Chinese authorities, the following were listed in Chinese Acupuncture and Moxibustion (22, 23), with slight differences on translation between the original Chinese and later Western publications: gastric pain, hiccup, abdominal distention, vomiting, diarrhea, dysentery, emaciation due to general deficiency, constipation, mastitis, intestinal abscess (acute appendicitis), numbness (motor impairment) and pain of the lower extremities, edema (beriberi), manic depressive psychosis.

In another book by the same name, Chinese Acupuncture and Moxibustion (24), these are listed: gastric pain, vomiting, hiccup, abdominal distention, borborygmus, diarrhea, dysentery, constipation, mastitis, enteritis, aching of the knee joint and leg, beriberi, edema, cough, asthma, emaciation due to general deficiency, indigestion, apoplexy, hemiplegia, dizziness, insomnia, mania.

As these indications may suggest, zusanli is often applied in emergency situations. In a report on emergency acupuncture (25), Zhang Xiaoping mentioned use of zusanli, accompanied by other points, for treating high fever, syncope, pulmonary abscess (with expectoration of sticky, foul, or bloody sputum), sudden vomiting, sudden diarrhea, fulminant dysentery, acute jaundice, acute hypochondriac pain, acute epigastralgia, acute abdominal pain, acute stranguria, sudden swelling (acute edema), and dysuria with vomiting (usually due to renal failure).

CLINICAL RESEARCH

There have been two main directions taken in modern clinical research with treatment at zusanli. One is the treatment of abdominal pain and spasm, usually affecting the stomach, gallbladder, or kidney. In this case, stimulation of the acupuncture point is reported to have immediate effects (within seconds or minutes) and patients often receive only one treatment. These reports are presented first. The other is the treatment of impaired immune functions, especially deficits in leukocyte and immunoglobulin production. In this case, stimulation of the acupuncture point is carried out daily, usually for 10–14 days consecutively, and this course of therapy might be repeated (sometimes after a short break of a few days). One of the studies mentioned below combines these two areas of concern: treatment of cancer patients suffering from abdominal pain (cancer patients usually have impaired immune functions, either spontaneously or as the result of medical therapies).

As might be expected, the relationship of zusanli to stomach function has been one of the main aims of research into the action of acupuncture stimulus applied at this point. It has been reported generally that needling zusanli can strengthen the contraction and digestive function of the weak stomach and relax the spasms of the stressed stomach. This latter indication has been investigated directly.

For example, in the 1984 Journal of Traditional Chinese Medicine (4), a group at the Gastroenterology Section of the hospital affiliated with Guiyang College of Traditional Chinese Medicine published a report on needling zusanli while administering the fiberoptic gastroscopy test. This test, in which a fiber optics tube is inserted through the mouth, down the throat, and into the stomach and then into the duodenum, tends to cause gastric and pyloric spasms. The authors of the study, relying on previous laboratory animal and clinical acupuncture investigations, believed that needling zusanli would be a reasonable treatment for the induced gastric spasms. In the article’s discussion they said that “No few recent studies indicate that zusanli needling has a regulatory effect on gastrointestinal tract function.”

Their patients were treated by standard Western medical methods that included premedication with atropine sulfate and valium; but about 10% of their patients suffered from persisting gastric or pyloric spasm, and these patients were treated by needling zusanli on the right side (the patients were lying on their left side during the gastroscopy procedure, making the right leg more accessible). The needle technique was to use rapid insertion, an insertion depth of 3.5–4.0 centimeters (about 1.5 cun), and an insertion angle towards the abdomen. The needle was twisted and rotated with “moderate stimulation,” until a propagated sensation from the treated point to the abdomen was felt. The needle was retained until the examination was over. According to the authors, this treatment relieved the spasms of 59 of the 60 patients so treated. The duration of needling required to get relief was within a few seconds in 9 cases, one minute in 13 cases, 2 minutes in 13 cases, 3 minutes in 12 cases, and 5 minutes in 12 cases.

A similar study was reported in the 1987 Journal of Traditional Chinese Medicine (5). In this case, the authors, from the China Medical University affiliated hospital, treated the control group with atropine and valium, but not the acupuncture group, who were treated, instead, at zusanli. The point hegu (Large Intestine-4) was also needled. As with the other study, patients were lying on their left side and acupuncture was administered only on the right side.

Electroacupuncture was utilized after obtaining the qi reaction by manual stimulation. The electric stimulus, at 2.5 Hz, was administered for 10–15 minutes prior to beginning gastroscopy. The needles were withdrawn after the gastroscopy was completed. The authors reported that 68 out of 70 patients had satisfactory introduction of the gastroscope; it worked as well as the drug therapy. Further, while patients in the control group reported some dizziness and malaise after treatment (probably due to the drug effects), this was not reported in the acupuncture group.

Along somewhat similar lines, elderly patients with epigastric pain were recruited for a study of zusanli at the Wuhan Hospital of Traditional Chinese Medicine, reported in the 1992 Journal of Traditional Chinese Medicine (6). The author pointed out that this pain syndrome usually arises from stagnation (which is a type of excess) on a background of overall deficiency, and that zusanli is an ideal point because it can alleviate the gastrointestinal local disorder while providing tonification.

Zusanli was punctured to a depth of 1.5 cun, followed by twisting and thrusting the needle to attain the propagated qi reaction (soreness and distension that radiates to the epigastrum). The needle is retained for 10–20 minutes, during which time it is maneuvered 1–2 times in cases of severe pain. The author presented three sample cases of successful treatment: two with billiary pain and one with stomach pain. According to the reports, the pain would be alleviated within 10–20 minutes of beginning the treatment.

A short report on needling zusanli to alleviate renal colic, which, in China, is usually treated with atropine or dolantin, appeared in the 1993 Journal of Traditional Chinese Medicine (7). The author needled patients bilaterally at zusanli with a needle depth of 2–2.5 cun (which is deeper needling than usual), with rapid twisting and rotation for strong stimulation for 1–2 minutes. The pain was reported to be alleviated promptly. The same treatment would be given again if the pain returned, in place of using injection of drugs.

An extensive review of using zusanli in abdominal surgical applications and abdominal pain, alone or as the main point in an acupuncture treatment, was presented recently by Cui Yunmeng and Qi Lijie (35). Among the applications and findings (outcome details not included here) were these:

· Acute appendicitis: patients would first be treated at zusanli with strong stimulation applied for 3–5 minutes after getting the qi reaction; if the abdominal pain was obviously reduced, the patient would then be treated by non-surgical methods, mainly by additional acupuncture applied at zusanli; if the pain could not be reduced, the patient was treated surgically.

· Post-operative pain: patients could be treated by injection at zusanli. According to the report, injection of vitamin K3 at this point, but not intramuscularly elsewhere, would provide pain relief for all patients; injecting water at the point brought pain relief to 73% of those treated. Referring to previous research, the author mentioned that needling zusanli could raise the pain threshold and inhibit pain transmission in the nervous system, especially in the abdominal area.

· Acute abdominal pain from various causes: electro-acupuncture at zusanli was used to treat pain due to acute pancreatitis, appendicitis, biliary ascariasis, renal and urethral calculus, and adhesive intestinal obstruction. Treatment provided prompt pain relief; and recurrence of pain within 24 hours was only 30% in those receiving acupuncture at this point. Differential treatment (using various acupuncture points according to standard Chinese medical diagnostic categories) did not improve the outcomes.

Although abdominal pain is the main focus of treatment with zusanli, the point is also used for leg pain and for temporomandibular joint pain. The latter application comes about because the stomach meridian runs along the face, crossing the temporomandibular joint (see Figure 3). A report by Cui Yunmeng (30), detailed the results of treating 60 patients with temporomandibular joint pain, difficulty opening the mouth, and problems with mastication. The author used single point acupuncture, stimulating zusanli only on the side of the body corresponding to the side of the face that was affected. The needle was stimulated to get the qi reaction, with an insertion depth of 1 cun, retaining the needle for 20–30 minutes. Patients received just 1–6 treatments, typically 3–4 treatments. According to the author, 39 patients were cured, and 15 cases were markedly improved; the other 6 showed minor improvement. Cui also reported (35) treating chest pain in the area of the mammary gland caused by soft-tissue injury, intercostal neuralgia, and acute mastitis, needling zusanli only on the same side as that affected by pain. As with the facial pain, the rationale for using zusanli for chest pain was that the stomach meridian runs upward across the ribs, through the mammary area.

The treatment of abdominal pain by needling zusanli was investigated in cancer patients at the affiliated cancer hospital of Harbin Medical University, reported in the 1995 Journal of Traditional Chinese Medicine (28). The patients were not getting relief from standard pain medication. The cancer cases included liver cancer, post-surgical stomach cancer, recurrent colon cancer, and abdominal lymphosarcoma.

Zusanli was treated on both sides, using either the reinforcing or reducing stimulation technique, depending on the traditional diagnosis of the patients. After attaining the needling sensation, the needles were retained for 15 minutes. Acupuncture was administered daily for two weeks as a course of therapy. In all but 11 of the 92 cases so treated, there was some degree of pain relief. Minor pain was alleviated in all cases, but more severe pain was usually only partially remitted. Still, in the group rated as having moderate pain, one-third attained pain relief that persisted for one month or more. The authors reported that there was pain relief during the needling session, and that persisting results could be attained after several consecutive days of treatment (typically, the full 2 weeks). They summarized the ability of the single point treatment to alleviate the cancer pain as follows: “If the duration [of suffering from cancer pain] is short, pain grade is low, tumors are small in size with no or little metastasis, the effect [of acupuncture at zusanli] is good....Also, the effect is related to the mental state of the patients. If they are full of confidence and cooperative in the treatment, better results can be expected.”

The authors cited earlier research (1989) that purported to show that needling zusanli could inhibit the nerves that cause the condition known as qi counterflow, which often causes spasms and vomiting. They also cited earlier research (1987 and 1990) with laboratory animal studies revealing that the corresponding zusanli point on animals yielded significant analgesic effects. Finally, they suggested that needling zusanli could have an anticancer activity (thus alleviating pain by reducing the impact of the cancer), because earlier research (1989) had shown that needling this point could increase the number of T-cells and improve the activity of natural killer cells.

The immunological action of needling zusanli has been the subject of some clinical research. For example, a group or researchers at the Zhong Guan Cun Hospital in Beijing and members of the Chinese Academy of Traditional Chinese Medicine (9) reported on the effects of stimulating zusanli with laser radiation or heat (provided with a focused flashing light source that measurably raised the skin temperature). They stimulated the bilateral zusanli points by either of these methods for 10 minutes at a session, once daily for 14 consecutive days. According to their report, healthy elderly individuals (60–77 years) treated by either method showed significant increases in peripheral blood leukocytes and total immunoglobulins.

A study exploring the ability of needling at zusanli to treat leukopenia was reported in a recent issue of the 1998 Journal of Traditional Chinese Medicine (10). In this case, leukopenia from various causes, mainly unknown etiology, with some cases from side effects of drugs and radiation or secondary effects of advanced diseases, was treated with acupuncture in 14 days of consecutive sessions. After a one week break, another 14 days of consecutive sessions was applied. The needles were inserted to zusanli on both legs, at a depth of about 1 cun. With twirling and lift-and-thrust maneuvers, the qi reaction was attained (soreness and distension), and then the needle was retained for 20 minutes with manipulations every 5 minutes. According to the report, there were significant improvements in immunoglobulin levels (IgG, IgA, and IgM; though IgG, which causes joint inflammation in arthritis patients was reported to be reduced in 2 patients of this group who had advanced arthritis), in C3 (complement protein 3), and in phytohemagglutinin test. According to the author:

Zusanli is a point for recuperating the depleted yang, and also one of the important points for strengthening the body resistance. Its action in health preservation has been paid due attention by doctors of successive dynasties....Acupuncture at zusanli can enhance both the specific and non-specific immunological function of the body.

Interestingly, although zusanli has been described in the past as treating cold conditions of the stomach (but, in the Nei Jing it is indicated for stomach heat), it is not usually depicted in the traditional literature as recuperating depleted yang. The one exception cited in the historical review above is the statement in the Jia Yi Jing that one could stimulate zusanli to treat “cold and numbness when the kidney qi is shriveling.” Rather, the point is frequently said to “regulate qi and blood.” Nonetheless, the depiction of zusanli invigorating the yang, which is not specifically mentioned in the modern acupuncture textbooks, is relied upon clinically in the treatment of impotence (zusanli is combined with a few other points). While one can say that anything that improves body function strengthens resistance to pathological influences (in the case quoted above, specifically to infections, since immunological function is then described), the traditional literature does not appear to emphasize this action. The author’s statement thus reveals how Chinese researchers can skew the explanation of what has been done in past dynastic periods to fit their particular findings.

ACUPUNCTURE MECHANISMS RESEARCH

Because of the importance attributed to zusanli in modern times, it has been a point commonly tested in evaluations of how acupuncture might work. That is, in attempting to find modern medical descriptions for the functions of acupoint stimulation, various responses of laboratory animals are determined. Zusanli on animals is located on the lateral tibial prominence, 1/5 of the distance from the knee to the ankle (11). This method of finding the point corresponds to the human measurement system, in which the distance from the knee to the ankle is said to be 16 cun (zusanli, at 3 cun, is thus about 1/5 the distance).

One suggestion about how acupuncture functions is that nerves are stimulated at the point (this yields the qi reaction as the sensory aspect, but can also involve non-sensory signals), and signals transferred along nerve pathways yield the ultimate therapeutic effect. There are two possibilities that may be considered:

1. The nervous system transfers signals directly from the acupoint to the organ that is being treated. The importance Chinese doctors attach to obtaining a propagated qi sensation along this pathway would imply this mechanism is involved.

2. The nervous system transfers information to the brain first, which then yields the response that affects the target area.

Both of these mechanisms could be involved in the total effect, along with release of substances from the nervous system into the blood stream during the transmission of signals. The released substances could interact with the endocrine and immune systems to generate systemic effects. As Cai Wuying concluded in his article on acupuncture and the nervous system (33): “Acupuncture stimulates peripheral sensory nerves and their endings, increases cutaneous blood flow and microcirculation, and releases neurotransmitters, neuropeptides, and hormones.”

To test the involvement of the nervous system, laboratory animal experiments were utilized in which nerves in the legs of animals were severed and it was shown that the effects of needling the point equivalent to zusanli could be stopped (23). Other experiments indicated that by blocking the nerve trunks related to the acupuncture points with procaine, the increase in white blood cell counts that are accomplished by stimulating zusanli (usually along with other points) is also blocked. This would suggest that nerve transmission is, in fact, an important part of the full range of therapeutic functions.

In the case of epilepsy, a laboratory animal experiment was reported in the 1992 Journal of Traditional Chinese Medicine (12), with needling at zusanli. The authors concluded that: “All the observations lead to the presumption that electroacupuncture when applied at zusanli exerts seizure-suppressing effect through a pathway of hypothalamic arcuate nucleus to brain stem raphe nucleus, to hippocampus.” The pathway leading from the acupuncture point to the brain stimulation, which released neurotransmitters to affect the other parts of the brain, was not investigated in this study, but a transmission via nerves is certainly a reasonable explanation. This is especially so since the effects on the brain were immediate: showing up shortly after the electro-acupuncture was started and diminishing when acupuncture therapy was stopped. The transmission from the acupuncture points were depicted in another study (26) this way: “the afferent impulses from the acupuncture points may activate the enkephalinergic neurons in the periaqueductral gray matter, especially in the dorsal part, and trigger the release of opiate-like substance which in turn acts on the nucleus raphe magnus.” The afferent impulses refer to nerve transmissions from the acupuncture site to the brain. In this study, bilateral zusanli were the points selected for stimulation.

Another study of zusanli on the brain was conducted in rabbits (29), in which it was shown that stimulating the zusanli point markedly increased blood flow in the cerebral tissues. The effect could be seen immediately after the stimulation began (first measurement one minute after initiating needle stimulus), and it increased during the next several minutes). The authors compared the effects of electroacupuncture stimulation with manual twirling manipulation of the needle using either the reducing or the reinforcing method. They reported that electroacupuncture had a much greater effect on the cerebral blood flow, while the two manual methods produced a lesser effect of the same nature, with no evident difference between the results of reducing or reinforcing methods. Presumably, the change in blood flow, which has also been reported to be a result of scalp acupuncture (see: Synopsis of scalp acupuncture), is accompanied by changes in brain activity.

In a study of immunological effects of needling zusanli mentioned in a review article (13), it was reported that the total white blood cell count of rats and rabbits could be increased markedly by needling zusanli, reaching a peak value with five consecutive days of treatment. However, this effect could only be achieved when the nervous and adrenal systems were intact. Aside from white blood cell counts, several other beneficial immunological effects of needling or moxibustion application at zusanli, either alone or in combination with other points, were mentioned in the review article.

In a study of hormonal effects, electro-acupuncture at zusanli was administered to dogs who had impaired adrenocortical function after three weeks administration of prednisone (34). Zusanli was treated bilaterally for 30 minutes, three times per week, for three weeks. Control animals received a similar stimulus either at points on the bladder meridian close to the adrenal glands (BL-22, -23, and 24) or at a non-acupuncture point. According to the report, ACTH was markedly improved during acupuncture therapy at zusanli, was only slight improved by acupuncture on the bladder meridian points, and not affected by treatment at the non-acupuncture point. Serum cortisol markedly improved in the zusanli group during the three week course of therapy. The authors pointed out previous research indicating that needling zusanli in several animal models (rabbits, cows, and sheep) could increase plasma hormones, and that the adrenocortical hormones were being stimulated via the hypothalamus (which is encompassed by the brain). An effect of acupuncture on the higher brain center was suggested as a possible basis for the hypothalamic-adrenal response.

It is not clear that such mechanistic explanations contribute very much to the actual clinical practice of acupuncture, though they do lend support to the Chinese contention that attaining the qi reaction and, in some cases, the propagated qi sensation, may be critical to attaining success in the treatment (see: Getting Qi). These reactions are felt by the patient and obviously represent successful interaction with the nervous system.

For example, in a study reported in 1989 Journal of Traditional Chinese Medicine (14), in which asthma patients were treated at acupuncture points zusanli and two lung points (taiyuan and chize, Lung-9 and Lung-5), it was found that the patients experiencing a strong propagated needle sensation got good results, while those who experienced little of this sensation had poorer results. In the case of zusanli, the direction of propagation was downward; for chize, it was mainly upward, with 20% of patients reporting radiation in both directions. The authors commented:

Whether or not acupuncture produces needling sensations bears a close relationship to the therapeutic results. Centuries ago, it was pointed out in the Nei Jing that the results of treatment can be obtained only when needling sensation reaches the site of disease....During acupuncture, the doctor’s attention should be given to needle manipulation in order to elicit adequately strong sensations. Strong sensations not only lead to more ideal results but also improve the objective indicies....”

SIMPLE COMBINATIONS WITH ZUSANLI

Because zusanli is so widely used by acupuncturists, it is naturally included in combinations with numerous other points. Certain combinations appear with especially high frequency. Below are some examples of treatments that specifically involve a small number of points. Probably the most frequent combination is with hegu (Large Intestine-4). This combination was mentioned in the story about inducing childbirth and in one of the gastroscopy trials, and is also described in some of the acupuncture mechanism experiments. In Modern Clinical Necessities for Acupuncture (15), treatment of this combination of points is cited as a successful treatment for the new application of giving up smoking.

In a study on the immunological effects of acupuncture (16), 120 patients suffering from pain syndromes were treated with acupuncture at zusanli and hegu. The researchers selected these points because:

For years, Chinese authors described that acupuncture can have a stimulating effect on cell-mediated immunity. In fact, some experimental research suggests a fairly good increase of T-lymphocytes after acupuncture stimulation at zusanli and hegu acupoints, as well as an increase of lymphoblast transformation which persists for 24 hours after stimulation.

Treatment

was carried out with perpendicular insertion of the needles, with varying depth

depending on the patients constitution (range: 0.8–3.3 cm). Twisting and twirling manipulation of the

needles was used to attain the qi reaction.

Stimulation was continued, with one minute of stimulation at a time,

bilaterally, for each point, with a one minute break between stimulus

sessions. After 15 minutes, stimulation

of hegu continued by the same method,

but zusanli was stimulated by electrical apparatus at 90 Hz. The needles were withdrawn after 30

minutes. According to the authors, 77%

of the treated patients showed an increase in CD3 and CD4 cells 30 minutes

after completion of the acupuncture treatments. Based on analysis of immune changes over time, the authors

concluded that antibody-dependent cell cytotoxicity by monocytes was

strengthened, which is important for treating infectious diseases. Also, natural killer cells were stimulated

by the acupuncture; these yield cytotoxic activity against virally infected

cells and cancer cells. The authors

believed that their results, which included analysis of vasoactive intestinal

peptide (VIP) and endorphins, confirm the recent findings with regard to

neuroimmunomodulation (the regulation of the immune system via the nervous

system).

Other common pairings:

· Zusanli and neiguan (Pericardium-6). These two points were the primary ones used in a study of cancer therapy (8), though others were sometimes added for specific symptoms. It was claimed that the acupuncture treatment ameliorated the typical side effects of chemotherapy and radiation therapy (poor appetite, nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, dizziness, insomnia, and fatigue) and improved the immune functions (including leukocyte count and immunoglobulin levels). In a review article on acupuncture research (32), Kuang Yihuang and Wei Jia made reference to research published in 1981: “Not a few patients suffering from drug intoxication and allergy [reaction to drugs] have been treated by acumoxibustion. Reactions such as vomiting, arthralgia, involuntary muscle movements, tachycardia, proxysmal chronic bronchitis and hypertension from antimony artrate injection and T273 administration have been cured by needling zusanli and neiguan bilaterally for 10–13 sessions.”

· Zusanli and sanyinjiao (Spleen-6). In a study of cancer patients receiving radiation therapy (17), patients were treated with microwave stimulated acupuncture at zusanli and sanyinjiao. The needles were inserted to 1.5 cun depth, and manipulated by hand to attain the qi reaction. The needles were then attached to microwave stimulus to maintain a needling sensation. Treatment time was 20 minutes each day, for 10 consecutive days. Leukocyte levels, which had been lowered by the radiation therapy, were monitored. According to the report, this acupuncture therapy was more effective in raising leukocytes than Western drugs (including leucogen) given to a control group. Further, the acupuncture group started with greater impairment of leukocytes. In another study, the same two points were reported to aid recovery of movement in the intestines following abdominal surgery and to lower liver enzyme levels that were raised as the result of tissue damage during surgery (35).

The four acupuncture points mentioned here, zusanli, hegu, neiguan, and sanyinjiao, were used together as the main points in a study involving the treatment of pain due to stomach cancer (31). Needle stimulus was carried out by reinforcing or reducing method and needles were retained for 20 minutes. The patients were asked to concentrate their minds on the diseased part (the stomach) during the treatment. Acupuncture was given daily for 14 days; after a break of 2–3 days another course of 14 days treatment was given for a total of 4 courses of therapy lasting two months. The authors reported that 80% of patients experienced immediate analgesic effects; about half of those patients maintained good analgesic effects 12 hours after the treatment. After two months of regular treatment, over 90% of the patients attained good analgesic effects. Among a control group receiving Western medications for pain (including codeine and dolantin, prescribed as needed), the immediate effects of the drugs were superior to acupuncture analgesia, but after two months of therapy, the acupuncture effects were as good as the drug effects. The authors also monitored the effects of their treatments on the immune system, on chemotherapy side effects, and quality of life, indicating that acupuncture had notable benefits not matched by the Western medicine group.

Previous reports have shown similar responses to treatment at zusanli alone, so it remains unclear whether the more complex therapy used in this study was really necessary. Needling several points with adequate stimulus is more complicated for the practitioner and is more confusing for the patient who is asked to focus his or her mind on the diseased part.

There are also some needle groupings that are larger but have become somewhat standard practice and involve zusanli. For example, Miriam Lee, in her book, Insights of a Senior Acupuncturist (18), describes the combination of “antique points,” sometimes called “ten old needles,” which is comprised of bilateral acupuncture at five sites, including three of the sites mentioned above:

zusanli (Stomach-36)

hegu (Large Intestine-4)

sanyinjiao (Spleen-6)

quchi (Large Intestine-11)

lieque (Lung-7)

This combination is used for a wide range of disorders. Regarding zusanli, Lee reports:

It increases digestion, helps the body to absorb food, increases the production of gastric acids, and stimulates hunger. I needle it first because it tranquilizes the patient and protects them from fainting reaction to the needles. It increases the flow of energy and oxygen to the head, since the stomach channel begins on the head. When needling the stomach channel on the feet, all the qi is sent upward. After stimulating zusanli, you can see the face become infused with redness, glowing and warm. Technique is very important. I put in both needles and then de qi (obtain the qi). Then with my right hand on the needle in the left leg and my left hand on the needle in the right leg, with the needles inserted shallowly, I move both thumbs forward 240 degrees and backwards 120 degrees (2/3 of a full turn around forward and 1/3 turn back). This is done 3 times and then the needle is thrust a little deeper, turned as above 3 times, again thrust deeper and turned 3 times, for a total of 9 turns. It is important that both needles be turned at the same time....Repeat the turnings 9 times until the propagation of qi reaches the toes....After the qi has reached the end of the channel, pull the needle up above the channel and above the muscle but not out of the skin and leave it shallow, pointing in the direction the channel flows. In the case of the stomach channel, point it towards the foot. This is the technique for supplementation.

Although Lee emphasizes a particular stimulation technique, the previously mentioned research appears to demonstrate effective response to other methods of stimulation.

A similar approach was used by Wang Leting (27), a well-known acupuncturist in China who practiced there from 1929 to 1979. Regarding zusanli, he is reported to have said “For hundreds of diseases, don’t forget zusanli.” In his records of treatment for gastro-intestinal diseases, it was found that he had used zusanli more often than any other point, in 72% of 126 cases treated. His own formula for ten old needles was:

zusanli (Stomach-36)

zhongwan (Conception Vessel-12)

qihai (Conception Vessel-6)

tianshu (Stomach-25)

neiguan (Pericardium-6)

Although

this differs markedly from the one mentioned by Miriam Lee, he had a similar

formulation which he referred to as Shiquan

Dabu Tang acupuncture. Shiquan Dabu Tang (Ginseng and Tang-kuei

Ten Combination), is a qi tonifying and blood nourishing herbal formula that

has numerous uses, including counteracting adverse effects to Western medical

therapies. His formula is the same as

Lee’s, except that liqie (Lung-7) is

deleted and replaced by a combination five points: lingquan (Gallbladder-34), zhongwan

(Conception Vessel-12), taichong

(Liver-3), zhangmen (Liver-13), and guanyuan (Conception Vessel-4). He recommended this set for the treatment of

spleen-heart deficiency, spleen-kidney deficiency, and liver-kidney deficiency

syndromes.

REFERENCES

1. Ellis A, Wiseman N, and Boss K, Grasping the Wind, 1989 Paradigm Publications, Brookline, MA.

2. Wu Jing-Nuan (translator), Ling Shu, or The Spiritual Pivot, 1993 Taoist Center, Washington, D.C.

3. Maoshing Ni, The Yellow Emperor’s Classic of Medicine: A New Translation of the Neijing Suwen with Commentary, 1995 Shambhala, Boston, MA.

4. Cheng Yiqin, et al., The use of needling zusanli in fiberoptic gastroscopy, Journal of Traditional Chinese Medicine 1984; 4(2): 91–92.

5. Chu Hang, Zhao Shuzhen, and Huang Yuying, Application of acupuncture to gastroscopy using a fiberoptic endoscope, Journal of Traditional Chinese Medicine 1987; 7(4): 279.

6. Zhang Jueren, Treatment with acupuncture at zusanli for epigastric pain in the elderly, Journal of Traditional Chinese Medicine 1992; 12(3): 178–179.

7. Liu Guoliang, Treatment of renal colic with acupuncture at zusanli, Journal of Traditional Chinese Medicine 1993; 13 (4): 265.

8. Xia Yuqing, et al., An approach to the effect on tumors of acupuncture in combination with radiotherapy or chemotherapy, Journal of Traditional Chinese Medicine 1986; 6 (a): 23–26.

9. Peng Yue, et al., Effects of laser radiation and photobustion over zusanli on the blood immunoglobulin and lymphocyte ANAE of the healthy aged, Journal of Traditional Chinese Medicine 1987; 7(2): 135–136.

10. Wei Zanmei, Clinical observation on therapeutic effect of acupuncture on zusanli for leukopenia, Journal of Traditional Chinese Medicine 1998; 18(2): 94–95.

11. Hua Xingbang, On animal acupoints, Journal of Traditional Chinese Medicine 1987; 7(4): 301–304.

12. Wu Dingzong, Mechanism of acupuncture in suppressing epileptic seizures, Journal of Traditional Chinese Medicine 1992; 12(3): 187–192.

13. Cui Meng, Present status of research abroad concerning the effect of acupuncture and moxibustion on immunological functions, Journal of Traditional Chinese Medicine 1992; 12(3): 211–219.

14.

Sheng Lingling, et

al., Effect of needling sensation

reaching the site of disease on the results of acupuncture treatment of

bronchial asthma, Journal of Traditional Chinese Medicine 1989; 9(2):

140–143.

15. Wang Qi and Dong Zhi Lin, Modern Clinical Necessities for Traditional Chinese Medicine, 1990 China Ocean Press, Beijing.

16. Petti F, et al., Effects of acupuncture on immune response related to opioid-like peptides, Journal of Traditional Chinese Medicine 1998; 18(1): 55–63.

17. He Chengjiang, Gong Kehui, and Xu Qunzhu, Effects of microwave acupuncture on the immunological function of cancer patients, Journal of Traditional Chinese Medicine 1987; 7(1): 9–11.

18. Lee M, Insights of a Senior Acupuncturist, 1992 Blue Poppy Press, Inc., Boulder, CO.

19. Huang-fu Mi, Systematic Classic of Acupuncture and Moxibustion, 1994 Blue Poppy Press, Inc., Boulder, CO.

20. Bertschinger R (translator), The Golden Needle, 1991 Churchill Livingstone, London.

21. Ming Shunpei and Yang Shunyi, Advanced Textbook of Traditional Chinese Medicine and Pharmacology, Volume 4 1997 New World Press Beijing.

22. Zhang Enquin (Ed. in Chief), Chinese Acupuncture and Moxibustion, 1990 Publishing House of Shanghai College of Traditional Chinese Medicine.

23. Qiu Mao-liang (Man. Ed.), Chinese Acupuncture and Moxibustion, 1993 Churchill Livingstone, London.

24. Chang Xinnang (Chief Ed.) Chinese Acupuncture and Moxibustion, 1987 Foreign Language Press, Beijing.

25. Zhang Xiaoping, Indications and contra-indications in emergency acupuncture treatment, Journal of Traditional Chinese Medicine 1996; 16(1): 70–77.

26. Zhu Lixia and Shi Qingyao, Activation of nucleus raphe magnus by acupuncture and enkephalinergic mechanism, Journal of Traditional Chinese Medicine 1984; 4(2): 111–118.

27. Yu Hui-cha and Han Fu-ru, (Shuai Xue-zhang, Trans.), Golden Needle Wang Le-ting, 1996 Blue Poppy Press, Inc., Boulder, CO.

28. Xu Shuying, Liu Zhiqiang, and Liyu, Treatment of cancerous abdominal pain by acupuncture on zusanli, Journal of Traditional Chinese Medicine 1995; 15(3): 189–191.

29. Shi Renhua, et al., Effects of electroacupuncture and twirling reinforcing-reducing manipulations on volume of microcirculatory blood flow in cerebral pia mater, Journal of Traditional Chinese Medicine 1998; 18(3): 220–224.

30. Cui Yunmeng, Treatment of 60 cases of dysfunction of the temporomandibular joint by puncturing zusanli acupoint, Journal of Traditional Chinese Medicine, 1993; 13(3): 191.

31. Dang Wen and Yang Jiebin, Clinical study on acupuncture treatment of stomach carcinoma pain, Journal of Traditional Chinese Medicine 1998; 18(1): 31–38.

32. Kuang Yihuang and Wei Jia, An introduction to the study of acupuncture and moxibustion in China, part III: Review of clinical studies on acupuncture and moxibustion, Journal of Traditional Chinese Medicine, 1984; 4(4): 249–254.

33. Cai Wuying, Acupuncture and the nervous system, American Journal of Chinese Medicine, 1992; 20(3–4): 331–337.

34. Lin JH, et al. Treatment of iatrogenic Cushing’s Syndrome in dogs with electroacupuncture stimulation of Stomach 36, American Journal of Chinese Medicine, 1991; 19(1): 9–15.

35. Cui Yunmeng and Qi Lijie, Application of zusanli in surgery, International Journal of Clinical Acupuncture, 1998; 9(3): 317–321.

December 1998

Figure 1.