Chapter 1

What Is Shen (Spirit)?

The Chinese character for shen, usually translated as "spirit," has two components. To the right is the character which gives both the basic meaning and pronunciation, shen. In the book Tracing the Roots of Chinese Characters by Li Leyi (1), the following explanation of the earliest known form of the character is given: "Graphically, it is the curved lightening flashes appearing in the clouds. The ancient people believed lightning was the manifestation of god." To the left is the modified form of the character shi (as used to form a radical, which is the category designator), which Li explains: "Originally, it was the stone table for offering ceremonial sacrifices to the gods…characters with the radical shi always pertain to ritual ceremonies, worship, or prayer." Today, this character (shi) more generally means to make known, to manifest, to show; this is because the ritual ceremonies display the inner prayer and worship of people. We can say that the Chinese writing character which has been formed into shen to refer to the spirit implies the manifestations of a person's relationship to god [the small letter 'g' is used here because the Chinese reference does not specify the personal God, as in the Western Judea-Christian-Islamic tradition; still there are obvious similarities of ancient ceremonial sacrifices on stone alters]. Historically, Chinese culture recognizes a creator god, Pan Gu, a trinity of divine Emperors (Tian Huang, Di Huang and Ren Huang, the emperors of heaven, earth, and man, respectively) and of divine helpers who come in human form, You Cao, Fu Xi, Shen Nong (2).

The earliest known discourse on shen in the medical context is found in the Huangdi Neijing Lingshu, in Scroll Two. The document that comes down to us today is believed to have originated during the Han Dynasty, perhaps around 100 B.C. In a translation by Wu Jingnuan (3), the relevant section on spirit is titled "The Roots of the Spirit." The section, like others, begins with a question from Huang Di (the Yellow Emperor) which is answered by Qi Bo (the chief physician), who begins his explanation this way:

"Heaven abides so that we have virtue. Earth abides so that we have qi. When virtue flows and qi is blended there is life."

The starting point for an understanding of shen is the meeting place of heaven and earth, which is man. Heaven is the origin of the spiritual aspect of man and provides ongoing spiritual influences; earth is the origin of the physical aspect of man and it continues to affect his body; the interaction of heaven and earth, the spiritual and physical, provides life; the ongoing harmonious interaction of heaven and earth in man is essential to maintaining life. The physical aspect is described here as qi. There is a frequent misconception in the West that qi is ethereal or "energetic," and this is a misinterpretation (4); in the traditional system of thought, qi is substantive but also dynamic, likened to steam and mist.

In the discussion presented in the scroll, there is reference to not only the spirit (shen) , but to two other entities which should be discussed before proceeding (see chapter appendix for more details). One is hun, which is translated often (and in this specific text) as the human soul; in fact, it is depicted as a collection of 3 entities working together. Hun is manifested in dreams, and it is the aspect of the human that persists after death of the body; thus, hun has a meaning that correlates to some extent with the idea of the soul in Western thought. When Chinese texts talk about the ghosts of ancestors, they are referring to hun. The other entity is po (actually represented as 7 entities), sometimes described as the "animal spirit" but perhaps more accurately portrayed as the physical vitality. Its action keeps the body alive; it is still active when a person is in a coma or is "brain dead;" it is gone when a person dies. Neither hun nor po are the same as shen, and po is not the same as qi. We can say that in describing these three entities, the shen is differentiated from the other two: it is not the human soul nor the vitality of the human body. From the ancient Chinese view of embryology, the hun and po combine together with the seminal essence (jing) and give rise to the spirit (shen) .

Shen, hun, and po each have a "seat" in the body, a place where they are said to rest and take residence. Thus, even though each of them can influence all aspects of the human person, they rely on certain parts of the person as a base. This situation might be likened to our own experience of working in the community and interacting with our neighbors, then returning home as a place for recuperation, rest, family interactions, and maintaining personal identity. Shen rests in the heart and vessels; hun rests in the liver; and po rests in the lungs. Although these three entities are the dominant concern in the ancient texts, in keeping with the influential system of five elements, two other organ systems are identified as having their own spiritual characteristics which are not the same as, but might be likened to, the other three: yi (intention, planning, thought, wisdom) is associated with the spleen and zhi (will; the strength to carry out yi) is associated with the kidney.

Though we have all these terms depicting components of the person, it is shen that is the focus of most discussion in the field of Chinese medicine, because that is the entity that is under the greatest control via our behavior and it is the entity that displays the greatest influence over body functions. We can attempt to learn more about the spirit by examining what is thought to harm it and what can be done to avoid harm or to repair harm, which is a subject of the Lingshu scroll.

There are two types of harm that can come to the spirit, one is external, the other is internal: This division is also used in the discussion of other physical disorders (another category of causation, one that is deemed neither strictly external nor internal, is based on activities, such as eating, exercising, etc.). External harm was viewed as the effect of "dissolute evil," which is often referred to as an influence of "demons" (5) and, later in Chinese medical history, was shifted into the general category of "wind" (6). The concept of demons causing disorders in people permeated virtually the entire world in these ancient times, and demons were most often the causative factor suggested in cases of mental disorders (particularly outlandish, obviously strange behavior) and neuromuscular disorders (particularly ones that were sudden and dramatic, such as epileptic seizures). Today, we might convert this ancient concept to one with more modern characterization, in which something (which we would not call a demon, but would involve, for example, neurotransmitters and other neural regulators) causes a dramatic alteration in neurological functions.

According to the Lingshu scroll, such external adverse influences could be avoided by maintaining strength and balance:

The wise nourish life by flowing with the four seasons and adapting to cold or heat, by harmonizing joy and anger in a tranquil dwelling, by balancing yin and yang, and what is hard and soft. So it is that dissolute evil cannot reach the man of wisdom, and he will be witness to a long life.

These few words may seem to be simple instructions, but they are only the outline of what could constitute entire books of instructions. I would like to offer a brief elaboration to assist with the discussion of the nature of spirit.

"Flowing with the four seasons" has the meaning of staying in communion with nature. This concern, expressed already more than 2,000 years ago when cities were simple compared to those we have today, is not merely about dressing for the weather (which is implied as part of the next statement of adapting to cold or heat), but it refers to giving attention to many different aspects of nature: the rising and setting of the sun, the varying weather patterns, the changing plant and animal life, the different sensations of the body as the day progresses, and so on. Today, we isolate ourselves from nature: missing the sunrise in favor of an alarm clock; eating according to what is in processed food packages rather than what has just been grown and harvested around us; dressing independent of the weather and then relying on artificial heat and cooling; cutting away the forests to live among concrete, asphalt, and mechanized vehicles. Though there can be no turning back of the clock of progress, there are choices to be made in living in the modern world, such as the extent to which we relate to the natural setting. This issue of communion with nature is not about going to the store to purchase organic produce and encapsulated herb extracts; rather, this is about turning attention to natural cycles, to natural settings, and to relationships with plants, animals, mountains, valleys, water, sky, sun and moon.

"Harmonizing joy and anger" refers to not allowing any emotion to become dominant or extreme, but it also refers to the opposite problem of unnaturally avoiding experience of emotions by setting up barriers. The person who is calm as a result of pursuing wise and healthful practices that lead to a tranquil and easy nature can enjoy inner strength and healthy life. An important aspect of this is one's own dwelling place, which should be nurturing, tranquil, and restful. Too often today, much of life seems a battleground, whether it is at home, at work, or on the road traveling between the two. People who engage in extreme behavior are a centerpiece of the world of television, which has become an unintended learning resource for many children as they grow up and develop their attitudes.

Balancing yin and yang (and hard and soft) refers to development of a sense of appropriate response. Yin is a more withdrawn receptive state of being, while yang is a more outgoing and active state of being; both have their times for being appropriate. Remaining in a "yin" condition when yang is needed, or vice versa, results in disorganization of life and harm to the body and spirit.

What the text is calling upon people to do is to adapt a lifestyle that is, at this time in history, substantially different than the ordinary. It requires turning to the health of the spirit, calmness of the emotions, and to worship and prayer directed at the heavenly influences and away from the unconscious pursuit of earthly things that lead toward extremes, while remaining intimately in touch with nature.

At the heart of the matter is the calmness which comes from an understanding of the relations between heaven, earth, and man. As the scroll describes, emotions in the extreme, which disrupt calmness, harm the person's spirit (I have inserted explanatory comments):

Too much joy and happiness can cause the spirit to shrink and scatter and not stay stored [that is, not return to resting in the heart]. Sorrow and grief can cause qi to be blocked in the foundations so it does not move [these emotions especially affect the lung, the seat of po, the vitality does not spread through the body and the person has difficulty with getting around]. Great anger causes confusion and doubt and a lack of control [anger is associated with the liver, the seat of hun, the soul is no longer able to command the person, and seemingly random forces take control]. Fear and fearing cause the spirit to be unsettled, to shrink away and to be nonreceptive [fear is the emotion that, more than any of them, adversely affects the spirit and the body-one's planning, and will to carry out plans, shrink away and one is even afraid to be helped].

It may seem odd to worry about experiencing too much joy and happiness. People can place excessive emphasis on the frequent experience of these emotions; so much so that one ignores other important aspects of life. As a result, the emotion and its context become false indicators of reality and lead one astray. This is not to argue against joy and happiness that are a natural outcome of enlightened spiritual living when harmony has already been attained; rather, it is about a focus on these emotions apart from such harmonious living. The emotions that have the greatest potential for harm when excessive, in addition to the dramatic impact of anger, are fear, fright, worry, and anxiety. As the text goes on to specify: "The heart and mind with frightened and distressed thoughts and anxiety can result in injury to the spirit."

The prolonged experience of living a fearful life leads to dysfunction, weakness, and premature death. The Lingshu scroll continues:

Fear and fearing without release can result in injury to the seminal essence [jing]. The injured seminal essence can cause the bones to be diseased and deficient. At the time of reproduction, the seminal essence will not descend [this refers to the interchange between essential fluids in the brain and in the kidney as described in the ancient literature]. Thus, the five viscera, which are the controls and storehouses of the seminal essence, should not be harmed [by excesses in the emotions; the text includes a description of visceral harm from each type of emotional excess]. If they are injured it will result in loss of protection, and the yin [the substance of the body] will become hollow. The yin being hollow will result in lack of qi [which is important for replenishing the jing]. A lack of qi will cause death.

The deficiency of bones has many implications. At one level, this applies to the problem of osteoporosis, where the bones become fragile and readily break (often contributing to health decline and premature death). It also applies to the bone marrow, the source of blood cells; the spinal cord and brain are also considered a type of marrow of the spinal column. Further, this deficiency refers to the movements of the bones; hence, difficulty in walking is considered one of the outcomes of bone disease, as are severe pains that afflict the bones and joints, such as occurs with osteoarthritis. The loss of protection means not only susceptibility to external influences, such as cold and heat and infectious agents, but also loss of protection from internal disruptions that may yield growth of tumors, water swelling, and failure of the organs to carry out their critical functions.

In sum, shen refers to that aspect of our being that is spiritual and looks to the universe around, and is not focused on emotions. Shen draws our attention to the divine, contributes to wisdom, virtue, and calmness, and maintains our whole being in order. The spirit can be harmed by external factors if we fail to maintain vitality through good habits, physical strength, and adequate nourishment. The spirit can also be harmed by internal factors, mainly excessive emotions.

These are things that are, to a certain extent, under our control. While many external factors are beyond our control, our protection from them through lifestyle choices is not. While emotional reactions to various situations are spontaneous and beyond our control, the ability to return to equanimity is a skill that can be mastered. To investigate further the critical issues, it will be worthwhile to examine in some detail the matter of flowing with nature, a basic Taoist concept, so that a path to communion with nature and inner strength can be identified (Chapter 2), and to look at some of the Chinese ways for controlling the emotions (Chapter 3). These approaches are said to be related to benefiting the hun (ordering relations with the outer world) and po (stabilizing the inner world), respectively. After contemplating these means of staying healthy, it will then be worthwhile to consider Chinese medical treatments (mainly acupuncture and herb therapies) that can assist those who have been adversely affected by shen disorders.

References

- Li Leyi, Tracing The Roots of Chinese Characters: 500 Cases, 1993 Beijing Language and Culture University Press, Beijing.

- Wei Tsuei, Roots of Chinese Culture and Medicine, 1989 Chinese Culture Books Company, Oakland, CA.

- Wu Jingnuan (translator), Ling Shu, 1993 Taoist Center, Washington, D.C.

- Dharmananda S, Qi: Drawing a concept, 1997 START Manuscripts, ITM, Portland, OR.

- Dharmananda S, Disorders caused by demons, 1997 START Manuscripts, ITM, Portland, OR.

- Dharmananda S, Feng: Drawing a concept; the meaning of wind in Chinese medicine, 1999 START Manuscripts, ITM, Portland, OR.

- Needham J, Science and Civilisation in China, vol. 2, 1974 Cambridge University Press, London.

Appendix: Hun and Po

The following introduction to the hun and po was derived primarily from Joseph Needham's exploration of the subject (7) with supplemental information from a few other sources.

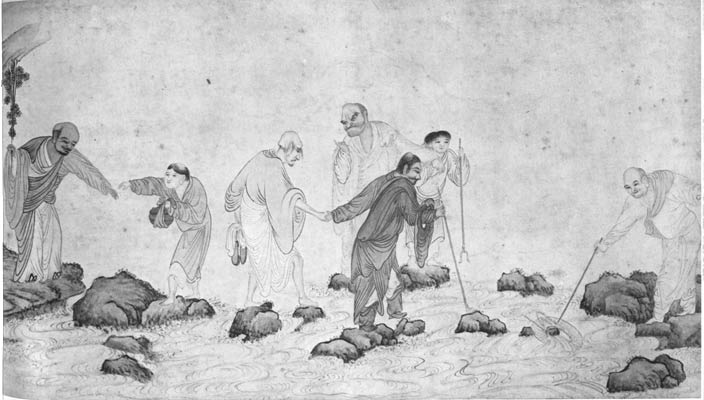

| More than 2,500 years ago in China, the idea developed, or solidified, that the human body encompassed two types of entities, usually described in English as "souls," which are called the hun and po. These two types of entities represent the yang and yin, respectively. The po, of which there are said to be seven, are of earthly nature, being most closely allied with the body substance, flesh. The hun, of which there are said to be three, are of heavenly nature. The hun and po are depicted in the painting below as two groups of wise men in a calm setting and in friendly discussion.

The hun originates in the heavens (as if from the air) and enters and exits the body through the hun gate (hunmen, acupuncture point BL-47); upon death, it departs to heaven. The Chinese practice of ancestor worship encompasses taking care of the departed hun, which, because of their residence in heaven, are thought to be able to help mediate the earthly human wishes with the gods. Further, it was thought that dissatisfied ancestral spirits (those who were not cared for by their offspring in succeeding generations) could cause illnesses or misfortunes. During life, the resting place of the hun is in the liver (the hun gate is at the back, near the liver).

|

The po is derived from the earth (as if from the soil) and enters and exits the body through the po door (pohu, acupuncture point BL-42); upon death it returns to the earth. The Chinese practices of burial of the dead encompass taking care of the po, which eventually blends into the earth and does not retain separate identity (as an exception, emperors were embalmed so that both po and hun could remain viable entities, retaining their original form). During life, the resting place of the po is in the lungs (the po door is at the back, by the lungs). If the qi and yin of the lungs is adequate, the po can remain vigorous.

One of the earliest discussions involving the hun and po was recorded in the 6th Century B.C., in which the following was said: "When a fetus begins to develop [into a human form and personality], it is due to the po. Then comes the yang part, hun. The jing [essences] of many things then give strength to these, and so they acquire the vitality, animation, and good cheer of these essences. Thus, eventually there arises spirituality and intelligence [shenming]."

There has been some disagreement in the Chinese literature as to when the po and hun actually arrive. For example, in the Du Shu Bian (16th century A.D.), it is said that the hun arrives during the seventh month of pregnancy (signaled by the ability to move the left hand) and the po arrives during the eighth month of pregnancy (signaled by the ability to move the right hand), rather than the other way around, with the po being first, which was the more prevalent view; in fact, it was often suggested that the hun entered the body after birth.

Around 80 A.D., a brief discussion of hun and po was presented in Paihu Tangte Lun (Discussions in the White Tiger Hall): "Hun expresses the idea of continuous propagation, unresting flight; it is the qi of the Lesser Yang [associated with liver/gallbladder], working in man in an external direction, and it governs the instincts (xing)....Hun is connected with the idea of weeding, for with the instincts, evil weeds [in man's nature or in his spiritual path] are removed. po expresses the idea of continuous pressing urge on man; it is the qi of the Lesser Yin [kidney/heart], and works in him, governing the emotions....Po is connected with the idea of brightening, for with the emotions the interior [personality] is governed."

Here, hun is expressed in terms of outer-directed activity: using the instincts to select a course of action and to avoid the pitfalls (evil weeds); po is expressed in terms of inner dynamics, adjusting one's emotional reactions and personality. This reflects the basic yin/yang dichotomy, with yin representing the internal and yang the external.

In an ancient book describing meditation practice, it was said that one should "be still, as if one had no hun;" that is, the drive to act, to do things, should be abandoned during meditation, leaving one able to remain motionless and focused on the inner condition. In a book on Taoism, it is said that one should "keep your hun from confusion, and it [the Tao] will come of itself, unify the qi and control the shen....All categories of things are brought into being by this; this is the door of power." Thus, the practice of meditation, avoiding the stimuli offered by civilization, and calming or regulating the ambition for outward change (while maintaining the drive for inner transformation, which will then affect the outer conditions) are activities associated with predominance of the po; searching the outer world for opportunities, applying thought and personal energy towards significant changes in the world, and relying on pleasurable stimuli that the world has to offer are associated with predominance of the hun.

The seven po may have originally been thought to be linked with the seven emotions. The seven emotions are described variously in English, but one such list is joy, anger, grief, fear, love, hate, and desire. For each of the emotions, there is an impact on the qi, so that if the emotion is quite intense, the qi may become significantly disturbed, leading to physical and mental disorders. In the Sanyin Ji Yi Bingzheng Fang Lun (Treatise on Three Categories of Pathogenic Factors), it is said that "In the interior of the body reside the jing and shen, the hun and po, the mind and sentiments, mourning and thoughts. They tend to be harmed by the seven emotions."

It is possible that the three hun were originally thought to be linked to the three major objectives of human action: relationship to societal authorities (in China, the Emperor and his representatives; in the modern world, it would include employers, law officers, governors, etc.), relationship to one's spouse (this would apply also to other relatives of the same generation and to neighbors), and relationship to one's children (this might also apply to others who are dependent upon your time and resources). It is a key tenet of Chinese philosophy, most clearly depicted by Confucianism, that relationships with others are important to both social harmony and to one's own physical and mental health.

It was thought that the hun and po could leave the body, even before death, though only a few of the 10 entities would be involved. Ge Hong, a famous Taoist, wrote during the 3rd century A.D. that: "All men, wise or foolish, know that their bodies contain hun and po. When some of them quit the body, illness ensues; when they all leave him, a man dies. In the former case, the shamans have formulas for restraining them; in the latter, the Book of Rites provide ceremonials for summoning them back. These po and hun are of all things the most intimately bound up with us, but throughout our lives probably no one ever actually hears or sees them."

In fact, it has been suggested that the hun, being of yang nature, may often depart the body during life and travel about, then return. Such adventures include certain dreams, the quasi-dream state that occurs at the border of sleep and which sometimes involves the sense of floating or sudden movement, and what we today call "out of body experiences." It is thought, at least in some Chinese communities, that insomnia, anxiety, fright and other states of mental agitation might arise if one of the hun stayed away too long. As a matter of diagnosis, patients reporting repeated nightmares are thought to be experiencing a disorder of the liver; the distressed hun give rise to the nightmare.

It was also believed that one or more of the hun could be virtually forced from the body of a child (less likely, but still possible in an adult) by a frightful experience; for example, being startled by a stranger. In such case, the child would become susceptible to disorders such as abdominal distress or epilepsy that were induced by demons. Other indicators of hun departure include listlessness, fretfulness, and simple continual sickliness. No doubt, conditions defined in modern times such as autism, attention deficit disorder, and other mental dysfunctions and psychological conditions have the potential of being classified, from the Chinese traditional perspective, as due to soul-loss or soul-disturbance. In China, that was a widespread scare in 1768, in which it was thought that sorcerers were stealing the hun of numerous people (and using the power of the dissociated hun for their own purposes).

The po could depart, or fail to be given sufficient rest and comfort, because of fright, deficiency of the jing, or constraint of the lung qi (perhaps due to excessive grief or sadness). In such a case, a person might suffer from weakened sensory ability, distress of the limbs (such as numbness), or might lose control of the feces (as the rectum was thought to be regulated by the po; the anus was known in earlier times as pomen: po gate). In the book Classic of Categories (1624), it is said that "Po moves and accomplishes things and pain and itching can be felt." Thus, from a diagnostic point of view, pain, numbness, and itching (as well as other sensory disturbances) and/or experience of serious elimination disorders (debilitated intestinal function) might indicate a distress of the po.

At death, the hun, being of yang nature, departs immediately, but the po, being of yin nature, departs more slowly. For some time, there were Chinese rituals, practiced at the time a person lost consciousness or died, attempting to call back the hun, so that it might reunite with the po, thereby restoring life and consciousness. It was also thought that if a person experienced a sudden and violent death, the po and hun might not be satisfied in simply dissolving into earth and heaven, but rather remain close by, as malevolent ghosts (gui). Such ghosts were thought to be able to cause accidents to happen and illnesses to arise seemingly out of nowhere.

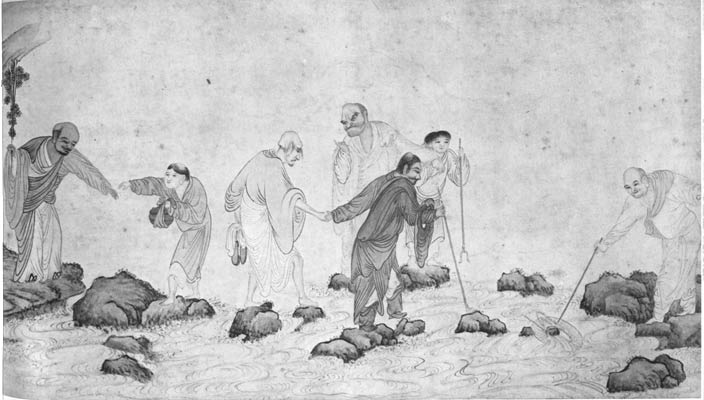

Detail section of the painting "The Five Hundred Arhats," by Wu Pin (1601) from the book Eight Dynasties of Chinese Paintings (1980 Cleveland Museum of Art). As explained in Chapter 2, the Arhats, commonly called Luohan in China, are Buddhist sages who share many ideals with the Taoists. One of the ideals is the natural state of mind, in which thoughts and ideas flow like water around obstacles, represented by the stones in the stream of this painting. The Arhats are crossing a turbulent section of the stream by making good use of those same obstacles, turning them to their advantage. The characters on either side have a calm and relaxed demeanor; those who are crossing the river are concentrating on the task at hand, which will soon be gone, just like the water rushing down the stream, and they will continue on with their journey. Two of the Arhats are crossing right, two are crossing left, and two are enjoying the experience as they pause on stones in the middle of the stream.